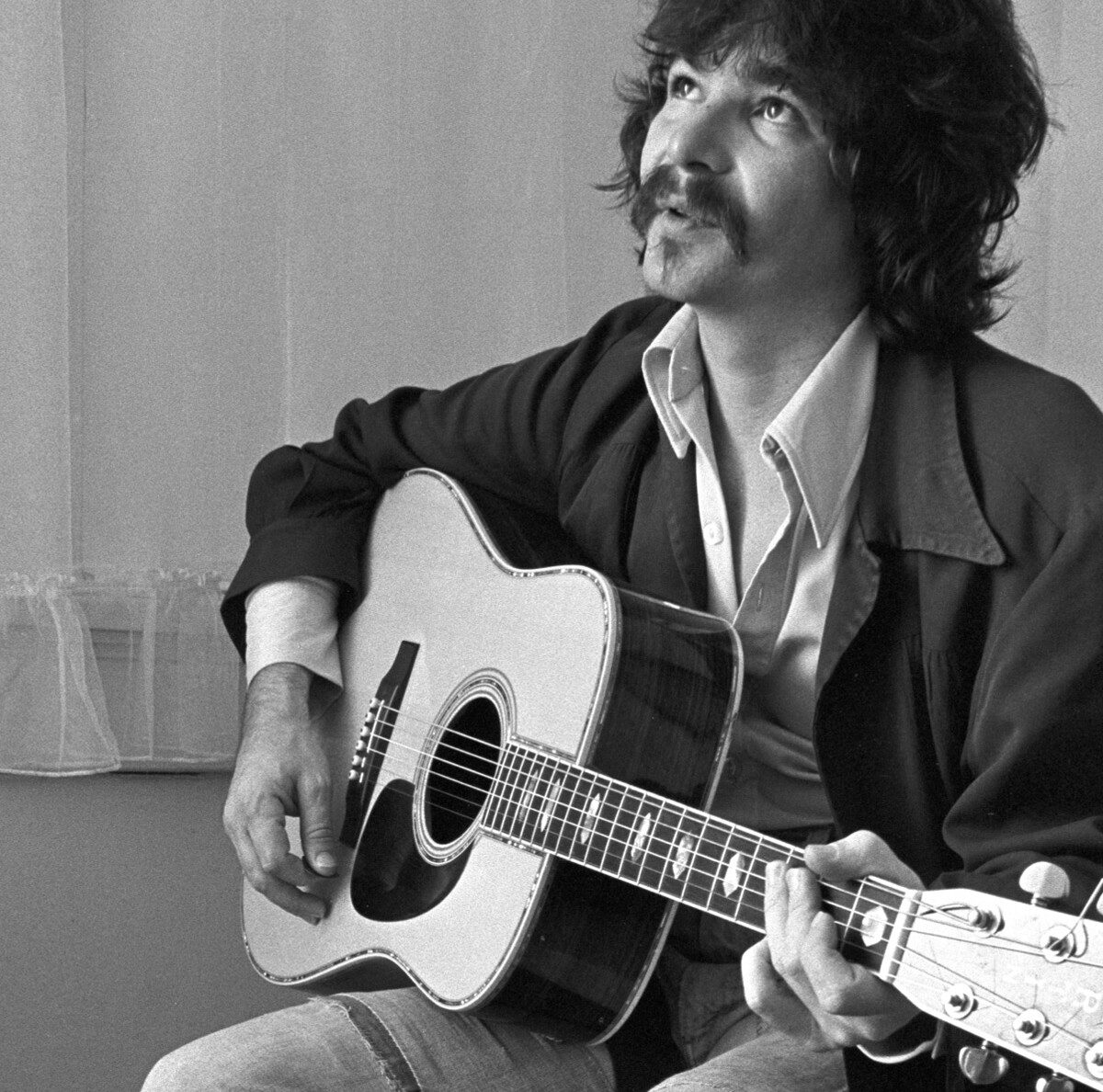

“You’ve got a song you’re singing from your gut, you want that audience to feel it in their gut. And you’ve got to make them think that you’re one of them sitting out there with them too. They’ve got to be able to relate to what you’re doing.”

—Johnny Cash

Anyone who follows Americana music probably saw the recent news that Jason Isbell and his wife, Amanda Shires, decided to return their Country Music Association memberships as a result of there having been no John Prine tribute at this year’s awards ceremony. Certainly, the decision to exclude the late Prine (as well as Billy Joe Shaver and Jerry Jeff Walker) was likely much more complex than will be presented here. However, suffice it to say, it feels like a good jumping off place in a discussion of what, if anything, constitutes the difference between folk music and country music.

In fact, I was sitting with my dad when the news about Isbell came on. Both of us are enormous John Prine fans, but whereas we, too, would be totally content to see tributes to him on every TV broadcast ad infinitum, we agreed that we both saw Prine “as more of a folk singer than a country singer.” What does that mean? Definitely John Prine is among the rare artists who, having penned some country hits in his legendary career, undeniably blurred the lines between the two genres. Though it’s easiest to just place him under the blanket classification of Americana, for the sake of completely subjective and admittedly pretentious argument, if forced, I think most would assign him to the folk rack at their local record store.