The brouhaha over La La Land being incorrectly announced as the winner for Best Picture before Moonlight received the award at the 2017 Oscar Awards attenuated discussion of Moonlight’s merits.

Did Moonlight deserve to win? Is it even a good picture?

Celebrated for its raw portrayal of growing up gay and black in the housing projects of Miami, Moonlight broke new ground, according to its admirers, for its presentation of its lead character, Chiron, as a victim of a homophobic world.

The child of a mother who is addicted to crack and turns to prostitution to support her habit, Chiron exists in an emotional isolation so intense that his ultimate turn to violence and drug trafficking seems inevitable.

As a painfully shy and sensitive child, he’s bullied mercilessly by his peers, and identified as a “faggot” by his mother, Paula, even before he’s entered adolescence. (It’s one of the film’s defects that we are told to think this for little to no reason.)

To the filmmakers’ credit, Chiron is more than a stock figure, at least until the implausible last act. The film’s ending, however, reveals the filmmakers’ intention not to be deterred from propagandistic purposes compounded by shallow thinking, even when given the opportunity to do so by the drama itself.

What’s wrong with Moonlight has to do with what’s wrong with progressive thinking in general. The working principle of the film comes down to this bromide: “To understand all is to forgive all.”

Therefore, tolerance reigns supreme; value judgments can only be judgmental; and all manner of evil must be accepted with a deterministic fatalism.

At several key points, the film might actually have turned in a more interesting and far more truthful direction.

The most important of these occurs in the first act when a drug dealer, Juan (played by Best Supporting Actor winner, Mahershala Ali) briefly becomes a father figure to Chiron. He meets the boy when rescues him from a “dope hole”—a boarded up apartment in an abandoned building—after seeing him being chased by a band of bullies.

Juan’s girlfriend, Teresa, and he give Chiron sanctuary in their apartment when he refuses to speak or provide any direction as to where he might live. (Teresa’s apartment will remain a refuge for Chiron whenever he needs it in the following years.)

Later, Juan takes Chiron to the beach and patiently teaches him how to swim, which resonates with the salvific role we hope this drug-dealer-with-a-heart-of-gold will play for the boy.

Juan’s role in Chiron’s life (and the picture) ends when he realizes he’s selling crack to Chiron’s mother. When Juan questions her drug use, she confronts him with his hypocrisy, demanding, “Are you going to raise him? Are you going to be his father?”

Juan’s role in Chiron’s life (and the picture) ends when he realizes he’s selling crack to Chiron’s mother. When Juan questions her drug use, she confronts him with his hypocrisy, demanding, “Are you going to raise him? Are you going to be his father?”

Those questions strike home enough for Juan to hang his head in shame while eating a meal with Teresa.

Here we have a real moral dilemma: one, unfortunately, Moonlight chooses to glide past rather than incorporate into the drama. Teresa reaches out to take Juan’s hand and comfort him—a likely action, given the characters involved, but also the most sickening one of the film. We are left to suppose that Juan is as trapped by his circumstances as everyone else.

A deeper film would, at the very least, have shown Juan suffering something far more than momentary emotional distress for this turn away from the chance at redemption. But the filmmakers have other purposes in mind and simply hustle Juan off stage.

That’s not to say that Moonlight, especially for a picture produced on a $1.5 million dollar budget, doesn’t have its skillful story telling passages.

Many of the best occur in the second act during Chiron’s high school years. He continues to be bullied, acquiring a nemesis in the charismatic thug, Terrel.

His mother, her youth gone, her health destroyed and no longer attractive to men, resorts to mugging her son for the few dollars Teresa lends him from time to time.

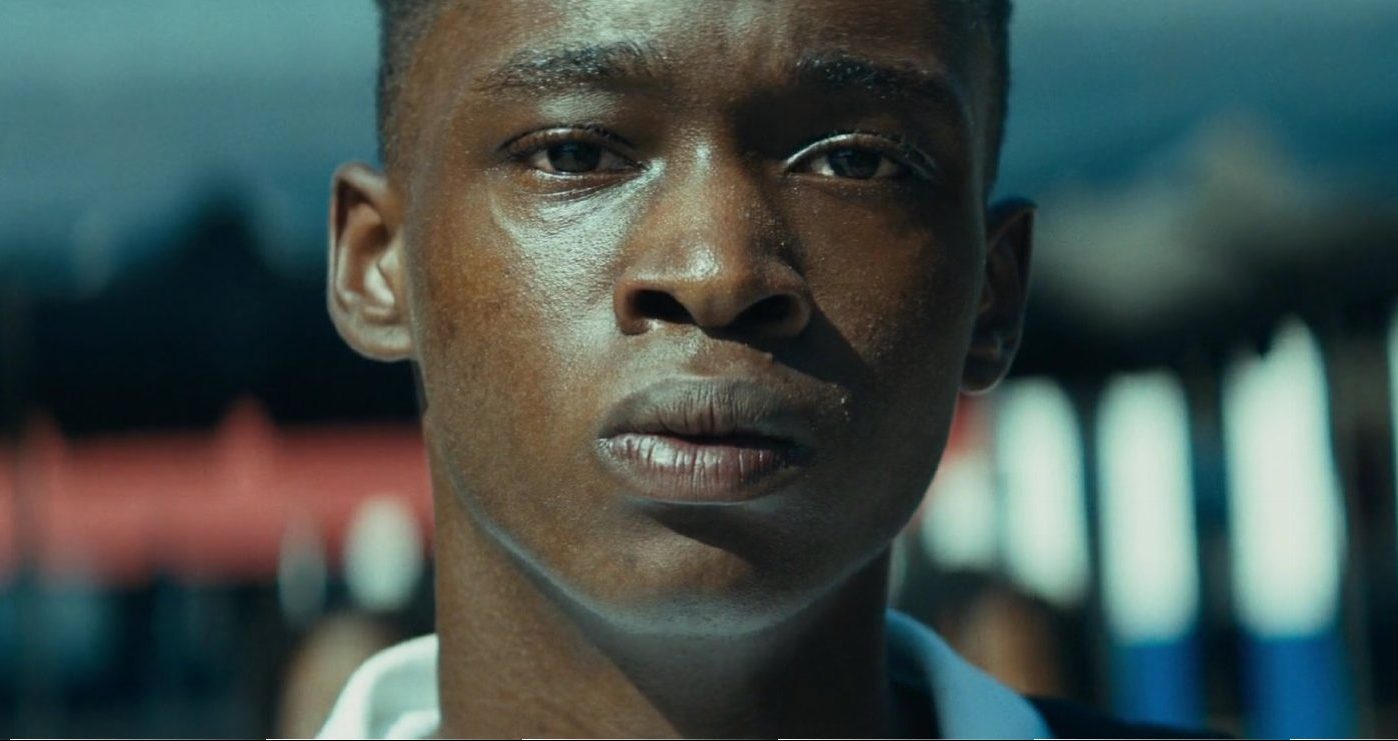

All of this increases our sense of Chiron’s isolation. Ashton Sanders plays Chiron during this period of his life, delivering a fine and subtle performance. He draws us in to Chiron as an ever more implosively repressed character.

As far as we know, Chiron has only one friend, Kevin. They become pals as children and their reliance on one another increases as they emerge into manhood. Their relationship reaches a new stage when they smoke a joint on the beach together and enjoy a brief sexual encounter.

The moment comes off as not only awkward, which rings true, but also unmotivated, which rings false. It seems the product of little but the message the filmmakers’ want to send. We know Chiron desperately needs companionship; we aren’t prepared dramatically for their relationship to be sexualized.

Why? To do so, perhaps, might have spoiled Chiron’s positioning as a perfectly innocent victim. It would have granted him too much agency.

Moonlight turns in an all-but allegorical direction when Chiron’s nemesis, Terrel, talks Kevin into playing what’s commonly known as “the knockout game.” Terrel dares Kevin to knock down a person of his choosing with one punch, and, of course, he chooses Kevin’s best friend, Chiron.

As students gather round, egged on by Terrel and his crew, Kevin slams Chiron to the ground with a roundhouse right. Chiron gets up but does not fight back or even put his hands up to block the next blow. Kevin hits him again and begs him to stay down so that the “game” will be over, but Chiron gets back up and awaits another blow, unprotected, if it’s coming.

Chiron’s refusal to put up a defense is a way of asking his only friend, Kevin, to make a late choice to side with him against his persecutors. Kevin can’t resist the peer pressure, however, and after one more blow Terrel and others nearly stomp Chiron to death.

Moonlight thus becomes a Passion Play, if briefly, because the Resurrection that follows is more Nietzsche and Wagner than St. Luke.

The next time the still-bandaged up Chiron enters class, he takes his revenge by smashing a chair over Terrel’s back and is promptly arrested—because, of course, the authorities always get it wrong.

back and is promptly arrested—because, of course, the authorities always get it wrong.

In the last act Chiron emerges as a homosexual Superman—the skinny, awkward teenager has rebuilt himself into a heavily muscled and superbly sculpted Mr. Universe. (It’s difficult not to see this character reinvention as part wish fulfillment and part apologia: if gay pride has become thuggish and bullying, well, there’s a reason.)

Now living in Atlanta, Chiron has followed in his one-time mentor’s footsteps, becoming a drug dealer high up in the food chain, complete with pimpmobile.

Kevin has become a cook and a father after his own stint in the joint. After what must be a decade, he calls Chiron to apologize. Kevin speaks of their possibly visiting one day. Chiron promptly takes off to go see him.

The dramatic tension of the final act comes from the sexual encounter we are led to suspect between Chiron and Kevin during this unannounced visit.

Their interplay certainly unfolds in the direction of a date, with Kevin preparing a special meal for Chiron and playing a romantic favorite song on the jukebox. Mostly, their bromance is simply tedious, by far the worst part of the film.

We never see any sexual grappling—I guess, we can suppose what we like—but only a tender moment of Chiron and Kevin holding each other. It’s the filmmakers’ final appeal to bless this sadly isolated moment of human connection in a terrible world.

Homosexuality is partly about human connection, of course, but that’s hardly all it’s about.

The film’s ending is mawkish and self-pitying and worlds away from the conclusions that might be drawn from the same material.

For example, maybe it’s not a good idea to have children out of wedlock, for fathers to desert their families, and people to sell and use drugs. That’s clearly not what we are supposed to be thinking about, though.

In the film’s coda, we see Chiron again as a boy. He’s on the beach at night, under the moonlight. He looks back over his shoulder at us, asking, it would seem, what we will make of him or do about him. The question is supposed to come off as being as urgent as its answer is evident: understand, accept, forgive, and above all, approve.

What’s needed—which the filmmakers willfully avoid—is deeper moral reflection about the world in which Chiron lives.

Moonlight has its merits, but it’s not nearly as good a film as rivals like Hacksaw Ridge, Fences and Arrival. It simply found its moment for its message.