They’re called motion pictures for a reason. More often than not, the key to crafting a great film doesn’t lie in the cleverness of the dialogue, but in how the story is told through images and the way that these are matched to sound and music.

There’s no better proof than director Christopher Nolan’s new movie, Dunkirk, a dramatic retelling of the rescue of the 400,000 British soldiers who were trapped on the North Sea following the fall of France to Nazi Germany in 1940.

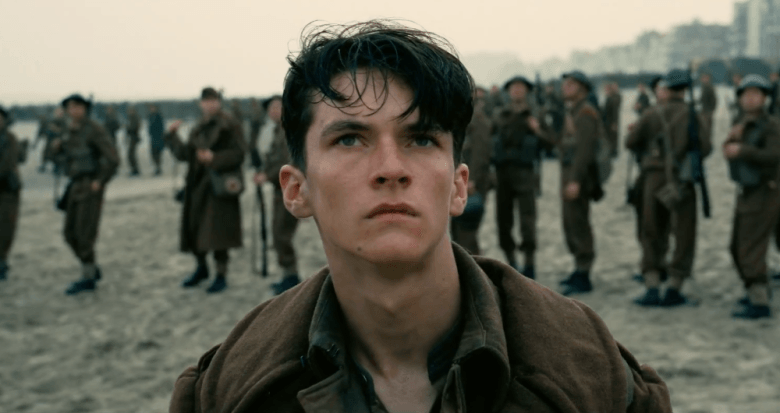

This is surely the best Hollywood war movie since Master and Commander. It may be an all-time classic. Yet many of its sequences have minimal or only barely intelligible dialogue. Nolan wisely avoids the use of extended exposition. The sights of crowds of soldiers upon the shore and of German propaganda leaflets declaring that the British troops are surrounded do enough to present the dilemma.

We are rarely told what is happening. In a series of intricately crafted tales, we are shown: on sea, land and air.

Ordinary Men in Appalling Times

The maritime adventure involves a weekend sailor known only as Mr. Dawson (Mark Rylance). A well-dressed member of the gentry, he decides to captain his ordinary pleasure craft across the channel in the hopes of picking up British soldiers whom he can bring back home. He does this as one of the many amateurs roused by Winston Churchill’s call for heroism from among the civilian coastal defense. He brings along with him his own son (Tom Glynn-Carey) and a barely pubescent local boy (Barry Keoghan). On their way, the three men rescue a victim of shell-shock (Cillian Muphy) who has been clinging to the overturned remnant of a torpedoed boat. As the sailor is determined not to go back, they soon realize that their countryman is a potential threat to themselves and their time-sensitive mission.

Meanwhile, at Dunkirk, a British Commander (Kenneth Branagh) worries about how many men he can get off the Mole, a long pier that extends out to the deeper waters past the shoreline. Roaming about on that strand are the frightened soldiers who are subject to persistent strikes from German dive bombers. Above them, we see a squadron of British fighter pilots battling the Luftwaffe — and their own chronic shortage of fuel.

Nolan cleverly develops each of these storylines, and he holds a few surprises in hand for his audience. But the film’s brilliance and its enormous rousing power comes from much more than this.

The well-researched movie captures a number of often forgotten or ignored truths described by real soldiers of the era. This means that the film includes hardly any gore, something which Dunkirk veterans report that they rarely saw in actual combat. It also captures the mood of tense seriousness.

Moreover, Nolan has the savvy to rely heavily upon his soundtrack. It mixes the noises of battle — gunshots firing, artillery shells going off, gasoline motors whirring, Klaxons ringing — with composer Hans Zimmer’s dark, tumultuous, propulsive score. Over and over again too, we hear the ticking of an unseen clock, which serves as a sort of auditory heartbeat. Not always subtly, this reminds us that the British have little time in which to save the best part of their army — and the cause of freedom with it.

The Precious Gift of Freedom

Sadly, some critics have felt it necessary to point out that Dunkirk presents us with few women and no minorities among the British forces. This is to say that it is historically accurate. That relentlessness in the current politics of political correctness should serve as a reminder of why this story is so important now. At a moment when the autocracies of the Middle and Far East are busy demonstrating their persistent indifference to the value of human life, perhaps we need to be made aware once more of how rare and precious democracy and liberty are and that these are far more significant than the petty resentments that may arise among us.

Dunkirk is a great film. And, although its story is set a lifetime ago, it is a timely one.