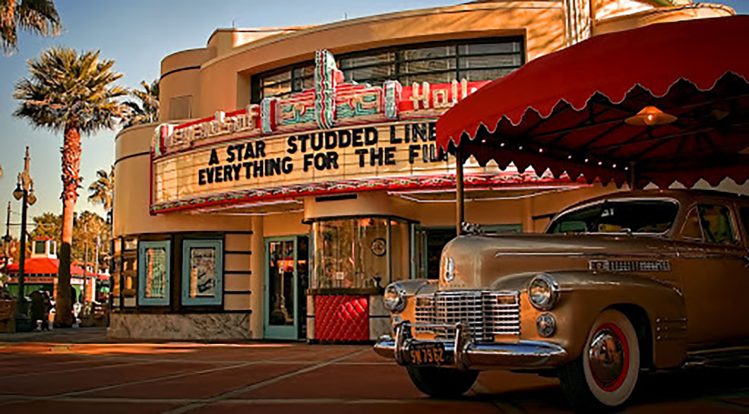

I sat behind the leather wheel of a sleek, gold Jaguar. The car purred confidently as I waited for the light to turn green. I looked to my right and saw a pretty female driver in the Mercedes beside me. She smiled; I returned it. She seemed impressed. After all, here I was, a young guy fresh out of college, cruising through Beverly Hills in a classic car. She didn’t have to know the Jag wasn’t mine, and that I was only taking it to get washed and gassed up for my boss. The light turned green, and I pulled away.

My boss at the time was a hugely successful TV producer. He had built an empire of sitcom hits going back 30 years, which is a remarkable run for anyone in Hollywood. I was hired at the tail end of his success. He had one show still on the air, but his long-running empire was near collapse. Still, he was a multimillionaire, and so thoroughly transformed by his unprecedented success that he seemed almost incapable of normal human behavior. We’ll call him Jerry.

I was Jerry’s “Executive Assistant,” which is a nice way of saying “lackey” or “doormat.” I almost never saw Jerry himself in or out of the production office – a tiny bungalow on a Burbank studio lot. He actively avoided me and his other assistants, as if making eye contact with us or learning our names would afflict him with some horrific disease. But what did we care? We were young Turks climbing the shimmering ladder toward Hollywood success. Sure, we were on the bottom rung, but at least we had made it onto the ladder.

Since Jerry wouldn’t engage me, I answered instead to my mercurial supervisor Sacha, the tiny but fierce mediatrix between me and Jerry. She was like a Tasmanian devil in a business suit. We worked in a two-story building – and Sacha’s office was directly above the assistants – just so we’d know our place. Sacha had an eye toward being a successful producer herself, and she wasn’t going to let anything stand in her way. Me and the other assistants were merely means to her end.

For some reason, Sacha was the only one who could gain an actual audience with Jerry face-to-face, so she took orders from him, then handed them down to us. (And that’s how I ended up cruising in Jerry’s Jag that morning.)

After filling the gas tank and dropping off the car at Jerry’s luxury condo, I got in my dirty gray Saturn and drove back to the office. No one smiled at the stoplights.

My next task was photocopying the script for that week’s episode. I always made sure to read the script so I could learn first-hand the craft of screenwriting. If you keep your eyes and ears open, being an assistant is just as good as (or better than) being in film school. While the Xerox machine spit out pages, Sacha summoned me to her office. My gut sank and my hands went clammy. I never knew what I was going to face when I entered her office.

Luckily, today she was in a good mood. Jerry had given her an assignment and she was delegating it to me. The task? Apparently, Jerry enjoyed Crunch-N-Munch popcorn without peanuts. But he had us buy the Crunch-N-Munch with peanuts, then sift through the box and remove all the peanuts. Jerry wasn’t even in the office to enjoy his Crunch-N-Munch (he was working from home that day), but we had to do this just in case he showed up and wanted a snack.

After the peanut removal project, it was close to lunchtime, and I volunteered to pick up Jerry’s lunch since it meant a chance to escape the office and catch some fresh air (as fresh as L.A. air gets anyway). So I made the usual stop at Delmonico’s in West L.A. and bought five lunches. It cost just over a hundred bucks in petty cash.

I drove to Jerry’s condo, left the sack of lunches outside his door, knocked to let him know it was there, then I hurried off. Minutes later, he would peek his head out the door to make sure no one was around, then he’d snatch the sack and duck inside.

So why did I buy Jerry five lunches? Was he hosting guests? Did he give some to his maids? No. He just liked to have options. He would look through each box of food – spaghetti bolognese, garlic-crusted halibut, rueben sandwiches, etc. – deciding which entrée he was in the mood for. Then he would choose one and toss out the rest.

Meanwhile, I’d drive back to the lot, buy a hamburger at the studio commissary, and sit there and wonder: Does a person like Jerry start out that crazy, or does thirty years of success, mountains of money, and nobody telling you “no” make you that crazy? If I ever ended up as successful as Jerry, would I become that unhinged from reality?

Eventually, Jerry’s show was cancelled, Rome burned to the ground, and he disappeared off Hollywood’s radar. Since those days, I’ve managed to climb some more rungs up the Hollywood ladder. I’ve written for TV shows, and even had my own assistants. I’ve asked them to pick up lunch (just one), but I’ve never made them separate the red M&M’s from the other colors, or darted away like a squirrel when I saw them coming. I know their names and what they hope to do with their lives. After all, they’re just trying to grasp the next rung on their way up the ladder, and I never want to be their “Jerry.”