People who imagine that they have cultivated cinematic tastes stick up their noses at the zombie genre. Perhaps Halloween is an opportune juncture to demonstrate to them its flexibility and artistic range.

Within its conventions directors have exercised immense flexibility, ranging from comedy to horror to social commentary.

Zombie films were launched by George Romero, whose gore-spattered Night of the Living Dead has become a cult classic. He followed these up with Dawn of the Dead (1978), Day of the Dead (1985), Land of the Dead (2005), Diary of the Dead (2008) and Survival of the Dead (2010), by which time it was about time for him to join the ranks of the dead, which he did earlier this year.

Even since, the creative juices of Hollywood have been flowing. Scores of zombie films have been produced in all languages, most of them, to be absolutely honest, flesh-creepingly dreadful. The 2015 film, Scouts Guide to the Zombie Apocalypse, is typical: was a low-budget, low-quality flop. “If Scouts Guide to the Zombie Apocalypse is the future, maybe the world should end,” said one critic.

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (2016) is a bit more original. It features the five Bennet sisters as masterful swordswomen who easily decapitate the zombies who are remorselessly encroaching upon Georgian England. Even the repugnant Wickham is unmasked as a zombie who manages to look human by eating pigs’ brains. But all’s well that ends well and wedding bells still ring for Elizabeth and Darcy at the close of the film.

Having conducted an exhaustive survey of the merits of the zombie genre by studying four of the best contemporary films — 28 Days Later (2002), Shaun of the Dead (2004), I Am Legend (2007), and World War Z (2013) – a number of strong positive qualities emerge from the genre.

There are some caveats, of course.

First of all, most zombie films are violent. Scientific studies have failed to reach a consensus on what kind of being zombies are, but by definition they are flesh-eating, aggressive and dangerous. So between zombies biting people and people decapitating zombies, there are buckets of gore.

Second, in most apocalyptic zombie films (ie, nearly all of them), uninfected people live in isolated communities where they fend off zombie attacks and study how to rebuild the human race. As everyone knows, isolated communities in Hollywood films are incubators either of gentle innocence or perverse weirdness. 28 Days Later unfortunately opts for the latter; three survivors, a man, a woman and a teenage girl arrive at an isolated military compound only to discover that the women-hungry, half-mad soldiers have grim plans for them.

With that in mind, the best zombie films convey important messages.

Solidarity. Snappy dialogue is not, regrettably, characteristic of zombie films. But as one character says solemnly in 28 Days After, “we need each other”. In a crisis which threatens to destroy all civilisation, everyone has a role to play. No one is useless. And having seen humanity disintegrate as the zombifying virus infects your friends and relatives, you appreciate your companions all the more.

Self-sacrifice. In the penultimate scene in I Am Legend, Will Smith’s character, US Army virologist Robert Neville, blows himself up to save his two companions who are carrying a vial of serum which will save the world. Nearly every zombie film has a scene in which heroic characters give their lives for the greater good.

Scientific method. Science plays a larger role in some films than others. The scientific contemporaries of the characters in Pride and Prejudice and Zombies were discovering oxygen and phrenology and had very rudimentary notions about viral infection. It is almost miraculous that they survive at all. However, films like I Am Legend and World War Z focus on thoughtful men scratching their chins, staring into the sky and scribbling down equations. Inspiring stuff!

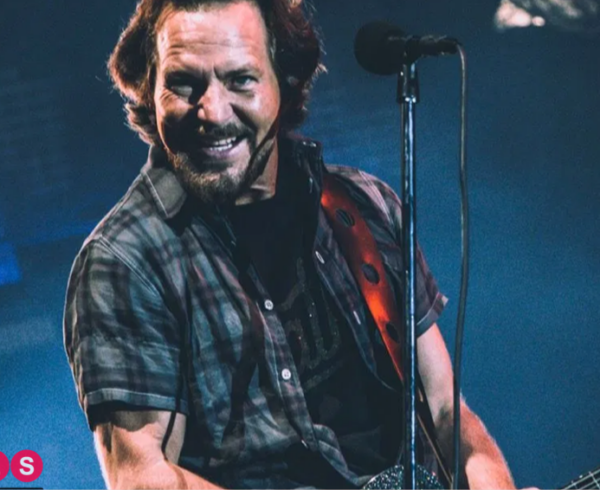

Sharp-edged social criticism. Shaun of the Dead is that rara avis in terra, a successful zombie comedy. Simon Pegg, who has since ascended to more expensive science documentaries like Star Wars: The Force Awakens, plays Shaun Riley, a no-hoper living in a London suburb. One morning he awakens after a binge and stumbles down to the shops to buy breakfast (a coke and an ice cream). All around him are shambling zombies, but they look no different from his drunken mates, and he brushes them off as he sleepily trudges home. What better illustration can there be of Thoreau’s maxim, “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation”?

Survival skills. Keeping alive in these dangerous environments is no picnic. The films teach lessons about useful skills like alertness, care for details, team building, how to open tinned food without a can opener, and how to build zombie traps. In Shaun of the Dead, the two “heroes” learn to use LPs like Frisbees to decapitate the slow-moving zombies.

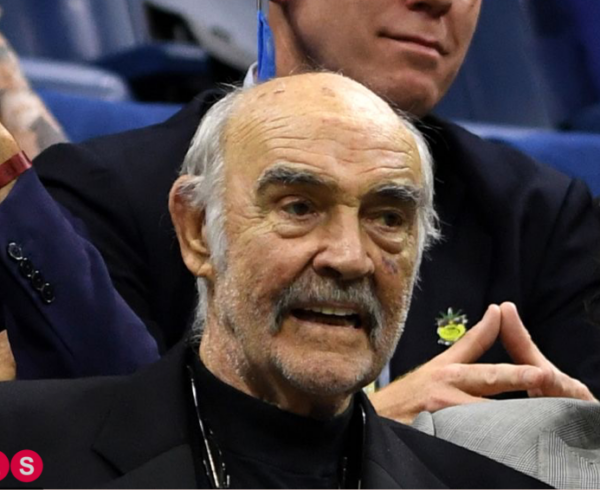

A critique of scientism. Nearly all zombie films trace the apocalypse back to scientific hubris and a reckless experiment. The opening scene of 28 Days Later, for instance, depicts animal liberationists breaking into an animal research lab at Cambridge University and releasing a chimpanzee infected with a “rage virus”. Ooops. Bad move. The best scene, though, must be the video clip that Robert Neville watches over and over in his Manhattan bunker: a humble-ever-so-humble British cancer scientist (played splendidly by Emma Thompson) announces that her team has reprogrammed the measles virus to cure cancer. Ooops. A seriously bad move. “Put not your faith in the conceit of scientists” is the salutary theme of nearly all zombie films.

The eerie beauty of urban landscapes. Modern cities are so crowded, 24/7, with people, people and more people. Zombie films erase them. You get magnificent shots of deer scampering across Fifth Avenue or a lone pedestrian walking across Westminster Bridge in London.

You get the idea. There are so many more positive and heart-warming lessons to be learned. But one must stop somewhere.

Sadly, it appears that only two zombie films were produced in 2017, one of them a Japanese film which went straight to video (known in English as Biohazard: Vendetta and in Japanese as Baiohazādo Vendetta). However, the future is looking bright. World War Z 2 is on the way, with Brad Pitt as the star and David Fincher as the director. All that’s needed now is a plot. I can hardly wait.

This column originally appeared at Mercatornet.com, and is reprinted by permission.