What Most Critics Missed in ‘Blade Runner 2049’

When I suggested reviewing Blade Runner 2049 for his magazine The Stream, its editor Jay Richards raised the obvious problem with the film from a theological viewpoint. Like its sequel, it takes for granted the “strong AI” position. That trendy theory states that our brains are just meat computers. So if we can build silicon versions that are equally complex, we’ll create other minds. Robert Marks explained in technical detail at The Stream why that’s unlikely. Essentially all computers do is compute. They execute orders, albeit with lightning speed. Not one of them has ever come even close to the initiative shown by a two-year-old child or even a puppy. Nor is there any evidence that we can design machines that show initiative, act freely, or can develop consciousness. At least not with silicon.

That’s reassuring. You don’t need to watch all the Terminator movies (or their brilliant, neglected predecessor, Colossus: The Forbin Project) to know this: Given the speed and ruthless single-mindedness of computers, we don’t want them to become self-aware. Not now, not ever. But that’s nothing new, really. We didn’t want there to be werewolves, either — things that mixed the vicious instincts of lower animal nature with human cleverness. We don’t want vampires, with the bloodlust (and wings!) of bats. A killer robot is not that different a bogie from the monsters who frightened our ancestors by firelight.

We Are Already Playing God

Jewish folklore even imagines a man-made robot, the Golem, whom arrant rabbis bring to life by magic. Tellingly, the spell to make the Golem come alive involves writing “God is Truth” on his forehead. But the first thing he does once he awakens is to change the inscription to read instead “God is dead.”

But forget the microchips. We are already playing God. We may not be taking sand that God made, turned to silicon, and forming it into life. But we are taking sperm and eggs that he made through us, and recklessly mixing them in laboratories. We’re tweaking their DNA and making plans to clone them. Maybe mix them with lower animals, to make creatures of uncertain status. (You thought it was bad when “gender” was reduced to a social contract. Wait till that happens to “species.”)

We have fecklessly and selfishly created hundreds of thousands of tiny humans, and frozen them in fertility labs across the country. There they sit in a literal, man-made frozen limbo. And we have no earthly idea what to do with them.

A Theologian who asked about the status of their souls would wait a long time for answers. Are they alive or are they dead? Should we adopt and implant them, or does that just compound the crime already committed against nature? Are they babies out in the snow whom we should rescue? Or tiny corpses of murder victims whom we ought not to use extraordinary means to revive and implant?

There Is Only One Kind of Human Soul

Blade Runner 2049 is a long, beautiful, solemn confusing film. It starts with the secular premise that man can and does play God — and that it’s inevitable. But like the first Blade Runner, it quails at the logical secular conclusion. The “replicants” created are not in fact the ruthless, focused appetite machines that we would expect a real robot to be. In fact, they seem to have “caught” human nature from their creators. And part of that nature, as both films insist, is uncertainty. Weakness, and need. And most important of all, compassion and love.

The replicants in both films are not like any machine we’ve ever built. They’re human beings, caught in different kinds of bodies. But the spirit breathed into them seems every bit as human as yours or mine. Just so, the children we dare to make in laboratories are as human as you or I. More the pity, for the huge majority, who will languish for decades in freezers, till the power supplies run out, or someone decides to unplug them.

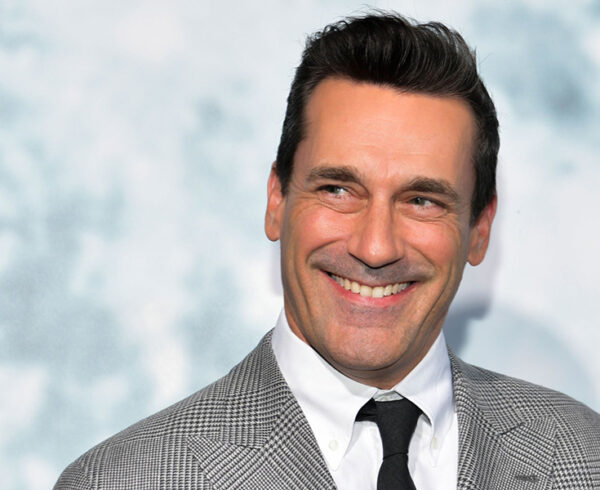

And that’s what renders the key plot question in Blade Runner 2049 curiously moot. It seems that at least one pair of replicants has gained the power to reproduce. You know, the old-fashioned way. Now, from the point of view of non-replicant humans, that would indeed “break the world.” So the L.A. cop played elegantly by Robin Wright warns in the film. Indeed, it would yield a new breed of super-strong, super-smart beings who might take over the planet. But the film bends over backwards to show us that replicants, and even AI “companions” who can live on portable flash-drives, are just as “human” at heart as the rest of us.

Sub-Creation Is the Best We Can Do

In other words, no matter how brilliant man becomes, even if he plays God and finds a new way to make life … what he makes will still have the same soul that God breathed into man. Indeed, you could even argue that in such a future, God would be breathing souls into such creatures (under protest?) just as He does today into test tube babies.

But there’s only one kind of conscious human soul. It’s the kind that God made for Adam. We cannot escape mortal limits, or even the Fall. How telling it is, isn’t it, that in none of the sci-fi films that imagine man creating a “new” form of life are those living things unfallen. They all bear the sin of Adam, which reminds us that whatever “creation” we attempt is really what Tolkien aptly called “sub-creation.” All our attempts to dethrone God as Creator will finally fail. We may scramble the puzzle pieces that He left us in countless unnatural ways. But they are still His, not ours. We cannot by our own powers wipe off the poisoned soil of Eden.

This column originally appeared at The Stream.