What Explains Today’s Wave of Nostalgia?

This weekend, I took in a double feature at my local cinema, consisting of the new remake of Stephen King’s It (based on a novel from 1986 and a miniseries from 1990) and the 35th anniversary showing of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (originally released in 1982). As I waited for the first film to start, the previews included a new Justice League movie (based on characters created well over half a century ago) and something by Steven Spielberg that appears to be little more than an homage to all of Spielberg’s films from the 80s. This year’s highest grossing blockbuster will undoubtedly be Star Wars: Episode VIII, which continues a franchise now 40 years old.

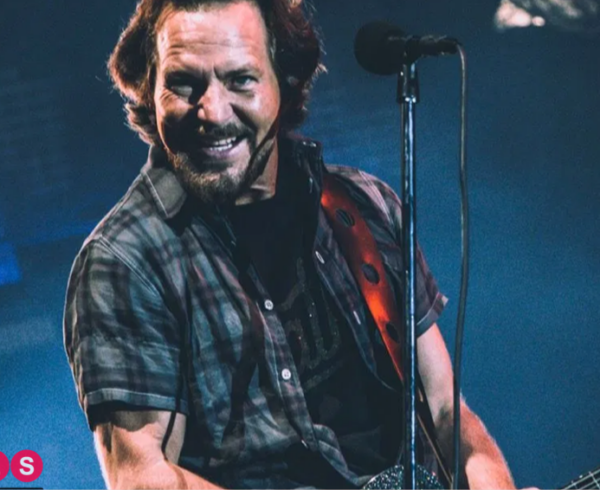

On television, critics have raved about the Netflix original series, Stranger Things, which relies heavily on shameless nostalgia-bait. On Showtime, Twin Peaks has just finished lurching its surreal way back from the early 1990s (albeit in magnificent Lynchian fashion).

So what’s my point? I’m surely not the first person to complain about Hollywood’s lack of originality and tendency towards sequels, remakes, and reboots. But what I’m interested in goes somewhat deeper. My question is this: why is society so obsessed with looking backwards instead of forwards? Why does nostalgia seem to be at an all-time high?

Looking Forward, Looking Back

It wasn’t always this way. In the 1960s and 70s, optimistic and imaginative visions of the future ran rampant, appearing in everything from Disneyland’s Carousel of Progress to programs like The Jetsons and Lost in Space. In the golden age of science fiction, gifted writers like Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov, and Philip K. Dick imagined a future ripe with possibilities, and while it’s true that some of these stories were grim and apocalyptic, at least an equal number reveled in the sheer excitement of what humanity might be able to accomplish in time.

Intuition tells us that nostalgia should be greatest when times are bad, when the memory of a better yesteryear provides relief from an unpleasant present. In reality, the opposite seems to be true. I’m calling this the “Nostalgia Paradox.”

The world of 2017 is objectively better than that of 1950 by almost every metric. People live longer, are healthier, and richer. They have more access to information, a multitude of options about what to do with their lives, and a markedly decreased chance of falling victim to violence. The civil rights of women and minorities have dramatically improved in the last 50 years, and the opportunities for a successful life have never been greater. Political freedoms have improved as well. Where you could have been arrested in the 1950s for being a communist, you can now openly hold whatever political position you like, vocally criticize elected officials, and run for office with a decent chance of winning, despite your racial or ethnic background.

And yet, according to the Real Clear Politics average of polls, a large majority of Americans think the country is headed in the wrong direction, and have thought so for a long time. So what’s going on here?

Yesterday and Today

I have a theory. In the 1950s, the memory of World War II was still fresh in people’s minds. This was a catastrophic event that caused most of the nation’s male population to be called overseas with no guarantee of ever coming back. Many didn’t. There was a real chance that the Axis powers would take over the world and usher in a new age of global darkness. I can only imagine what it must have been like coming out the other side of that period of fear and uncertainty, but there must have been a tremendous sense of relief, a sense that things could only get better.

Contrast that with today. While it’s true that we have been at war in the Middle East for coming up on two decades, these conflicts remain remote in the minds of most Americans. There is nothing comparable to the mass conscription of World War II, and many of us don’t even know people directly affected by the war. Meanwhile, we are all free to enjoy our iPhones, high-definition televisions, and endless portions of delicious, affordable food. To the extent that there are any real crises for us to worry about, they are mostly far away, if not physically, then at least emotionally. In short, we’ve had it too good for too long.

I’m not saying that we should long for another devastating, nationwide catastrophe to jerk us out of our collective stupor. Far from it. But the effect of being too comfortable is that we have forgotten what real hardship is, and we have lost our appreciation for how good we have it. With this in mind, it makes sense that we would conjure up romanticized dreams of an imaginary past, a past that in most cases never really existed.

There’s nothing wrong with indulging in a little nostalgia now and then; I’ll continue to go see The Wrath of Khan with you anytime you want. But a little perspective is always a good thing. Humanity is a tremendously inventive and innovative species, and if history is any guide, the future is likely to get better before it gets worse. A little optimism would perhaps do us all some good.

This column originally appeared at the Foundation for Economic Education. It is reprinted with permission.