“Menashe” Is a Beautiful Story of Family, Faith and Love

A movie that takes a sympathetic view of a faithful adherent to a Judeo-Christian religious group is as rare as a meteor from Pluto or a ski instructor in the Bahamas. It isn’t just improbable. Nowadays it’s nearly unheard of.

Yet that’s what the remarkable new movie Menashe is.

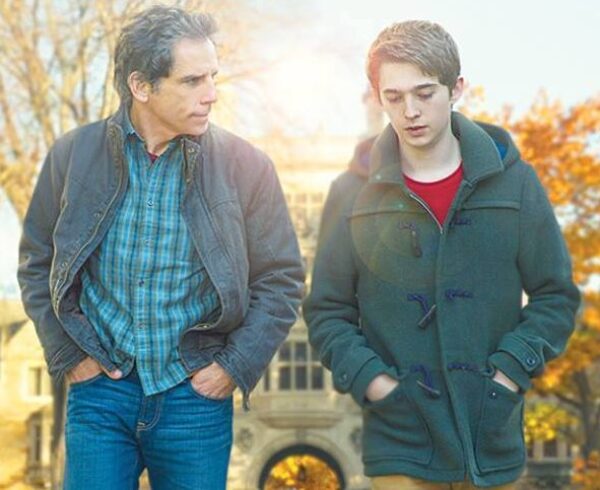

Loosely based on the real life of its lead actor Menashe Lustig, this Sundance Festival favorite is an affecting slice of life tale about a single, widowed father living in a Chasidic community in Borough Park, Brooklyn. The film, which is subtitled into English, is almost exclusively in Yiddish and performed by a cast of non-professionals who wear the customary black hats of faithful Orthodox believers.

The film’s conflict derives from Menashe’s wish to raise his son on his own. This is something that Chasidic Jews frown upon, as they believe that a child should always be raised in a household with a mother and father. For that reason, Menashe’s little boy Rieven (Ruben Nidorski) is being reared, along with his first cousin, by his brother-in-law Eizik (Yoel Weishaus) and Eizik’s wife.

The group in which Menashe lives really is a community. The word is not just a meaningless term in the service of political propaganda as it might be in an expression like the “arts community.” This means that Menashe respects its decisions. These are handed down by his elderly rabbi (Meyer Schwartz), his “ruv.” The rabbi’s determination is bolstered by his consciousness that Menashe works as a cashier and factotum at a local grocery store. So he has much less money to provide for his child than his brother-in-law, a successful real estate investor. At the same time, the rabbi is a goodhearted and thoughtful man who wants Menashe to become a mensch, a solid citizen and parent. To that end, he encourages Menashe to find a second wife and to create a stronger household for his son in order that he can return to him.

Menashe is relatively slow-moving and intimate, and its hero is a tubby, disheveled figure. There are no beautiful people in this movie and no action sequences. The opening credits of a typical Hollywood picture contain twenty times more violence and quite a bit more sex appeal. (One is reminded somewhat of Lincoln’s observation that God must love plain-looking people as he had made so many of them.) Moreover, the movie’s production values are mostly below the level of video taken on a more recent generation of iPhone.

But Menashe has something sorely lacking from the overwhelming majority of mainstream movies: three dimensional characters, a thoroughly plausible story and a wealth of soul.

Its events are revealed in a mostly episodic fashion. In this way, we see Menashe’s labors in his grocery store and his conflicts with his hectoring employer. We observe him listening to the sometimes sage counsel of his Latino immigrant co-workers. We watch him on a date with a devout widow seeking a second spouse of her own. Most of all, we witness Menashe’s scheduled visits with the son whom he deeply misses.

On few of these occasions is Menashe adroit or ingratiating. More often, he is obstinate and inept. What we cannot miss is his devotion and his love for his son.

The entertainment industry has long seen Chasids as a group who serve as amusing local color. They are simply background to the stories of the main characters: secular heroes and heroines working in upscale industries like advertising or publishing. This is perhaps better than the way Hollywood has treated the Amish and Mormons, exploiting the first population in reality television programs and mocking the second in plays and musicals. Yet it is not an approach that shows much respect, let alone any meaningful concern or understanding.

That is plentiful though in Menashe. The feat is made more impressive by the fact that neither the director Joshua Z. Weinstein, nor his co-writers, Alex Lipschultz and Musa Syeed, are Orthodox Jews.

Surprisingly, their achievements in writing are almost equaled by the quality and naturalness of the performances Weinstein elicited from his actors, who are non-professionals. This starts with the volatile but sympathetic Lustig in the title role. His performance is unlikely to be a sign of things to come. As a thespian working in a period when there is no more Yiddish theater, it’s hard to see how he will act much more after this in his native tongue. But his story and his presence will stay with you long after you leave the theater.