Godfather of the zombie film genre, George A. Romero’s death at 77-years-old has undoubtedly been a sudden and tragic moment for horror fans the world over. Not least because it came only a few days after the news that the American film director began seeking financing for the latest instalment in his “dead” series, Road of the Dead.

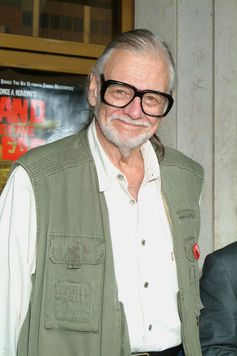

George A. Romero. The Everett Collection/Shutterstock

These days, the zombie has turned from the shuffling, flesh-guzzling monsters that first roamed the streets on that fateful night in 1968, to less gory, almost human creatures. The US television series iZombie, for example, which features a sentient zombie medical examiner, Olivia Moore, distinguishes between its thinking zombies and those who revert to primal, brain-eating beasts, affectionately referred to as “Romeros”.

Romero was a true master of the horror film, and has often been credited as having created the modern zombie genre. It is a testament to the legacy of Romero’s “dead” series – which started with “Night of the Living Dead” in 1968 – that the zombie figure, which has a long and troubled history, going back to slavery in the West Indies, has come to be associated so strongly with one man’s oeuvre.

Zombies like Olivia aren’t scary. And even more violent shows like The Walking Dead demonstrate ways that zombies can be controlled, or manipulated, while humans attempt to live some kind of normal life. At one point in the series, the group manage to ironically make a home in an abandoned prison, while zombies press against the fences outside.

But without Romero’s zombies, this modern outbreak could never have happened.

An independent triumph

Even those unfamiliar with horror films may recognise the iconic line, “They’re coming to get you, Barbara!”. The words are childishly intoned by a young man to his increasingly annoyed sister upon their arrival at a creepy Pennsylvania cemetery.

Unaware that the dead really have started to rise from their graves and stalk the living for their flesh, this apparently harmless moment of irreverent humour marks the beginning of Night of the Living Dead – to this day one of the most influential horror films ever made.

Produced with little more than US$100,000, the film went on to gross millions, and totally reshaped the landscape of independent film-making in the process. It also kick-started the career of a director who would contribute many other gems to the horror canon, from the bio-weapon nightmares of The Crazies (1973) – remade in 2010 – to the psycho-sexual backwater vampire in Martin (1978), and Stephen King’s screenwriting debut, Creepshow (1982).

But, more importantly, it refashioned the shuffling, possessed zombie of the 1930s and 1940s as a cannibalistic, unstoppable “force majeure”; a monster more in tune with the late capitalist times. These were creatures that were more than mere flesh-eaters, Romero’s zombies communicated and made plans, and would eventually learn to think and feel.

Our zombies, ourselves

More expertly, perhaps, than any before him, Romero managed to use the horror genre to tune into social issues. It is well-known now that the casting of black actor Duane Jones as lead character Ben in Night of the Living Dead was a fortuitous event, and not necessarily an attempt to politicise the film. But the closing images of Ben burnt on a pyre alongside the zombies he has been mistaken for is indicative of a social and racial awareness the director would expand on in later films.

In 2005’s Land of the Dead, for example, features the character Big Daddy, a black gas station owner who leads a zombie revolution against the privileged humans who live in the Fiddler’s Green outpost.

Despite following a similar formula to Romero’s first film – a group of survivors trapped by zombie hordes they must fend against – the sequels that followed “Night” were very different. They developed aspects of the zombie narrative that have been further explored and continue to be exploited by contemporary films, TV shows, novels, and even books on topics as varied as neuroscience and the economy. Romero created monsters that blurred the line between human and zombie. These were no longer just reanimated corpses, craving the flesh of their former kin, they were the very start of a new society.

Romero’s zombies are our future, if not our present; they are metaphors for a humanity living in the end times. Their abject and instinct-driven qualities remind us of the perishability and transience of life. The zombies’ endless hunger is like the physiological drives that dominate our existence, but also mirror the current neoliberal principles of the Western World. And their doom is akin to the inevitable demise of the human race in view of planetary crises like climate change.

![]() Though now we may have lost the horror genius that was Romero, his dead will walk among us for many years to come.

Though now we may have lost the horror genius that was Romero, his dead will walk among us for many years to come.

Xavier Aldana Reyes, Senior Lecturer in English Literature and Film, Manchester Metropolitan University. This essay originally appeared at Mercatornet.com, and is reprinted by permission.