Before moving on to writing a third novel, as I stated previously (Writing Fantasy Literature: A Personal Story – Part 1), I had two more important developments in my writing life.

The first was rather simple. Though my desire was still to write a really fine fantasy novel set in my own imaginary world, I began reading far more broadly. I still picked up occasional works of fantasy, especially when recommended by those whose opinions I most trusted, but I also began reading more poetry and contemporary fiction from excellent writers, and even creative non-fiction by great essayists.

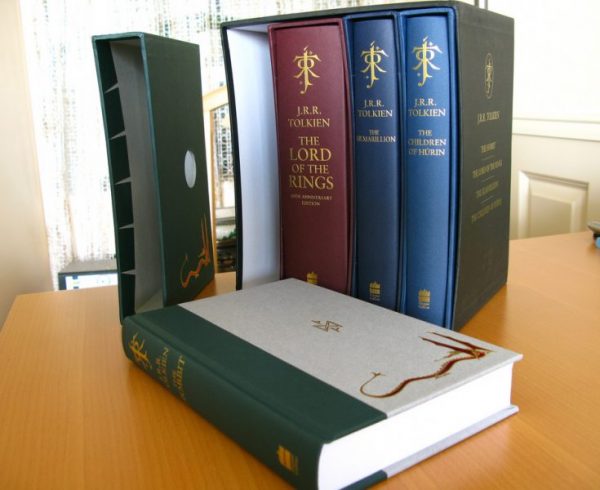

Wendell Berry became a favorite in all three categories. Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It joined The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion in my list of favorite works. I read more Hemingway, and I also read critically acclaimed, though lesser known, contemporary writers like Gina Ochsner and James Schaap.

The second development was more complex. In 2003, a dozen years after my first published novel—twelve years during which none of my fiction writing was getting published—my years of teaching classes on Tolkien, Lewis, and fantasy literature opened the door for some more serious scholarship. That led to the publication of several books: Following Gandalf: Epic Battles and Moral Victory in The Lord of the Rings (2004), From Homer to Harry Potter: a Handbook of Myth and Fantasy (2006), Ents, Elves, and Eriador: the Environmental Vision of J.R.R.Tolkien (2006), Narnia and the Fields of Arbol: the Environmental Vision of C.S.Lewis (2009), and A Hobbit Journey: Discovering the Enchantment of J.R.R.Tolkien’s Middle-Earth (2013), plus chapters and essays in several other books and magazines.

I also received invitations to give talks on fantasy—especially on J.R.R.Tolkien—around the country. All of this helped me to understand what aspects (especially of Tolkien’s writing) connected the most with readers. It also helped me realize what was most important to me personally in the writing, and what I wanted to accomplish, whether or not my work would ever become commercially “successful.”

I also received invitations to give talks on fantasy—especially on J.R.R.Tolkien—around the country. All of this helped me to understand what aspects (especially of Tolkien’s writing) connected the most with readers. It also helped me realize what was most important to me personally in the writing, and what I wanted to accomplish, whether or not my work would ever become commercially “successful.”

I know that for many, in this age of fantasy and superhero films, the draw of the fantasy genre is the non-stop action, the adventure, and (sadly) even the violence. But that was never the case for me. What I loved first and foremost about the genre was simply the sense of wonder and awe and enchantment.

In fact, despite the impression that Peter Jackson’s films might leave, J.R.R.Tolkien spends little time describing battles in The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings. The big battle in The Hobbit takes up less than three pages. He was far more interested in describing trees and flowers, landscapes and meals, and even aspects of the various cultures of Middle-Earth such as their poetry. The stories don’t so much move from battle to battle as they do from meal to meal. I thought that the reader truly immersed in those tales didn’t come away from them so much loving swords and sorcery as loving trees, and seeing mountains and meals, stories and songs, rivers and rabbits, as both magical and beautiful.

Of course, the stories also have compelling stories within and compelling characters. There is almost something important at stake. What happens really matters. They are still adventure stories of some kind. Thus the other aspect that really moved me was Tolkien’s portrayal of heroes and heroism, which was always rooted not in strength, nor power (neither physical or magical), nor prowess (with a sword or a wand), or in bravado or cunning, but in simple moral integrity—the decision to do the right thing no matter how difficult, painful, or risky.

After several more years of writing, I finally finished my third work of fantasy, a three-volume novel collectively titled The Daegmon War. Each book is just over 400 paperback pages. I found a publisher and signed a contract. I revised and submitted the finished first volume, The Gifted. The publisher hired an outside editor to help me with revisions to make the book both better and, of course, more sellable.

There was certainly room for improvement in that first volume—places the prose could be polished, sentences strengthened, issues where character motivation wasn’t clear. But the comments that came back were of a different nature. Several places the editor told me I couldn’t do something I had done. I was surprised. I’ve written several books about fantasy literature. I’ve studied some of the most important fantasy writers who paved the way for all that has followed since 1981. I even pointed out places where some great fantasy authors used the exact same technique, particularly J.R.R.Tolkien. “Tolkien wouldn’t sell if he were published today,” the editor replied. “You need to make your book more like Game of Thrones and less like the writings of J.R.R.Tolkien.”

Though I think the characters are compelling, the “world-building” is imaginative and enchanting, and what is at stake is worthy of epic fantasy, I also admit that there is plenty I could have done to improve the writing. And some of it I did. The editor had some very helpful suggestions along those lines—for example catching the overuse of passive voice which I am much better at spotting in the writing of my students than in my own. But she also wanted me to remove much of the descriptions of the landscapes and cultures, the food and the musical instruments that were not only part of my world-building, but one of the very things I thought most important. They don’t move the plot along, she said. Instead she wanted me to give—not just show through their actions, but explicitly state—the emotions of my characters. More like Game of Thrones was the repeated mantra.

In the end, I did a fair bit of rewriting and made a big compromise with the editor on the narrative point-of-view, also addressing some of her style suggestions. But when it came to my overarching vision for the book, I dug in my heels, gritted my teeth, and remained firm. Game of Thrones was the antithesis of what I wanted to write. Was my editor right? Was it true that Tolkien—a much better writer than I will likely ever be—would not sell if published today? Maybe so. But if it is true, then I’m willing not to sell either. I would rather write a book that is read by only a handful of readers but contributes something positive to the culture in which I live.

I want to write compelling and imaginative stories that will draw the reader in. I love a good action adventure. But I also want to offer something that makes people care more about meals, and trees, and the types of songs that would be sung, and art that would be hung on the walls by a tribe of shepherds living in the mountains as opposed to the fishing clan living along the coast.

Or maybe I’m just a stubborn old fool.

Thanks. Loved reading this.