Reflections From the River On Fishing, Writing, and Friendship

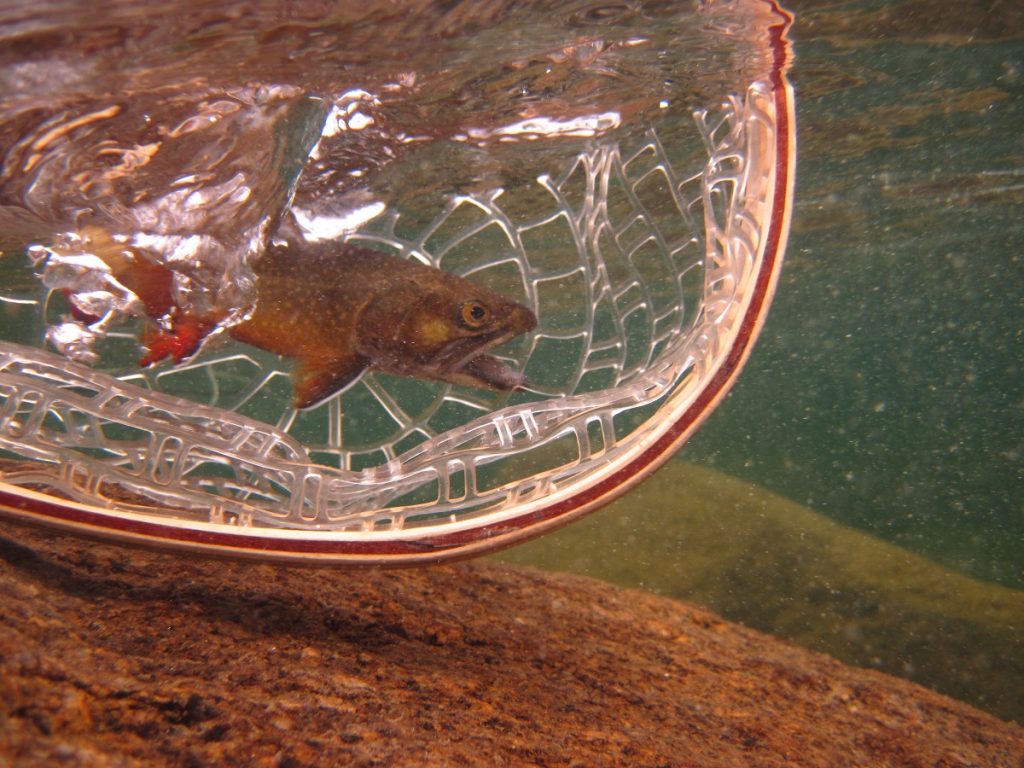

There is a certain attentiveness necessary when standing thigh deep in current, fly rod in hand, hoping a thin piece of invisible line will connect me to a surging fish.

I am aware of insects hovering over water, bouncing off branches, crawling around my feet. Of the movements of feeding birds. Of changes in the wind, and passing cloud-shadows. Of the tiniest dimples in the current.

Reading, like fishing, requires—and indeed fosters—a similar attentiveness. We live in an age of internet facts, and mistakenly confuse those for knowledge or wisdom. It is a vastly different thing to engage in a story or poem or essay that invites our imaginations into all sorts of connections and depths emerging from sustained attention.

Most of all, perhaps, writing cultivates attentiveness. A good story demands that I listen to its characters, pay attention to its world, and then humbly submit to what it is telling me. Crafting a creative essay or work of fiction requires that I pay attention to every word, every metaphor—as though it were an insect emerging from the bottom of my thought-stream, swimming to the surface, and flying away. Or returning to settle on the water, legs eggs. Get sipped in by a feeding trout.

Writing—like fishing—is not so much an expression of what I already know, but an act of attentive learning.

On Reading, Fishing, and the Moral Imagination

I think it was in books (especially fiction), and in spending time in the outdoors (especially fishing and visiting areas approaching wilderness), that my imagination really formed.

And by imagination, I mean not only my imagination as a writer, but also my moral imagination—my ability to have empathy and compassion for my fellow human travelers and image-bearers of God as well as care for God’s created world and other beings who share with me that creature-liness.

To engage as a reader in a world of fiction is to enter into the minds and thoughts and emotions of another. It is to learn to see the world as somebody else sees it. It is to understand through another’s eyes. That, of course, is the core of empathy.

Similarly, to sit in nature and observe—apart, for a time, from all the technologies that help set our human race apart—is to see the beauty and interconnectedness of God’s creation. Even fishing requires that I strive, imaginatively, to see the world the way a fish does.

A Unifying Idea (in the Midst of a Diversity of Approaches)

When somebody asks me what sorts of books I write, I sometimes laugh.

We live in a consumer culture that categorizes everything into little boxes having more to do with marketing than with life.

I write medieval historical fiction as well as fantasy. I write narrative non-fiction about nature, ecology, and fishing. I write biography, apologetics and literary criticism. I write about what is important to me, or what I would enjoy reading. I write to learn.

Yet in the midst of this mix of styles and topics, there are some important ideas that keep emerging.

One central idea is captured in a passage from C.S.Lewis’ The Abolition of Man.

There is something which unites magic and applied science while separating both from the ‘wisdom’ of earlier ages. For the wise men of old the cardinal problem had been how to conform the soul to reality, and the solution had been knowledge, self-discipline, and virtue. For magic and applied science alike the problem is how to subdue reality to the wishes of men: the solution is a technique; and both, in the practice of this technique, are ready to do things hitherto regarded as disgusting and impious.

On Body, Spirit, Art, and Nature

I am drawn to concepts of heroism.

My non-fiction writing often explores one or the other of two grave philosophical dangers—opposite deceits if you will. One is the denial of the spirit. The other is the denial of the body. Both deceits can easily turn us into amoral or immoral persons.

The more common deceit in the modern West is denying any spiritual reality. It has been argued that if there is no transcendent reality, then there is no basis for objective morality. But the deceit goes deeper: If humans are just complex biochemical machines, then free will is an illusion. If we don’t make choices, then we can’t make moral choices, and heroism is just an illusion. You end up like Bertrand Russell arguing there is no difference between writing a poem and committing a

murder.

The opposite danger is denying the reality or goodness of the physical world—including our human bodies. This is the deceit of Gnosticism. At the extreme, if our bodies don’t matter, and the physical world doesn’t matter, then our bodily actions don’t matter. It becomes irrelevant what we do to one another or what we do to the earth. Which turns out to be another way to destroy any moral basis for actions.

On Friendship and Creativity

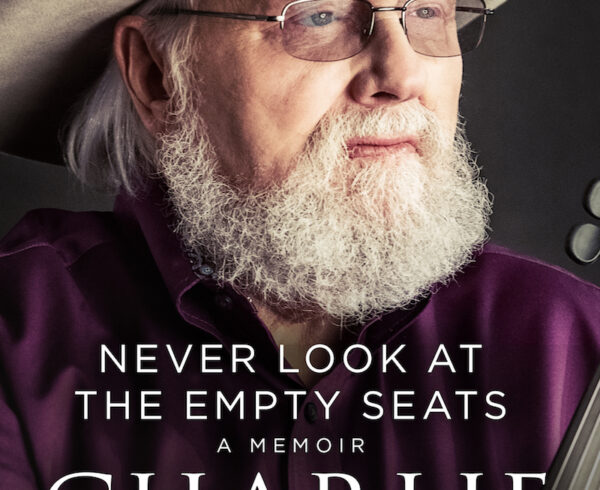

Friends of mine—especially other authors—have asked me what it is like to co-author a creative book, as I have done with my good friend David O’Hara.

Our first book together was more of a scholarly project. If I’m honest, I think co-writing was more of an excuse to spend time together than an endeavor driven by scholarly concern. I think it was just selfish. We no longer lived in the same state, and if our families were going to stay close, we were going to have to work on it.

But when we were done, I realized the book was much stronger than if I had written it alone. Part of it was the different areas of knowledge we brought to the project. But I think an even bigger part was just the practice of sharpening not only each other’s ideas, but also each other’s prose. Of course, this took humility as well as trust. That process both challenged our friendship, but then—like many challenges—made it stronger.

Our second book together, another more scholarly work on the works of C.S.Lewis, was even more deeply collaborative. And it was even clearer to me that through the compromises and combining of our styles and visions and voices, that the project was much stronger than any I could have produced alone. Not only did we have a better book, but I was individually a better writer because of Dave.

By the time we worked together on what I considered primarily a creative project—a work of narrative non-fiction about fly-fishing and ecology—it was our third book together.

Maybe it’s good that wasn’t our first book together. Collaboration on something creative (rather than scholarly) requires even more vulnerability. We put more of ourselves in it, and so critiques can be felt more personally.

But I think the result was something even stronger than just the collaboration of minds. I think the book more than any other not only grew out of friendship, but I think it reflects that friendship. It has the flavor of it.