New Study Explains Why a Simpler Lifestyle Creates a Feeling of Well-Being

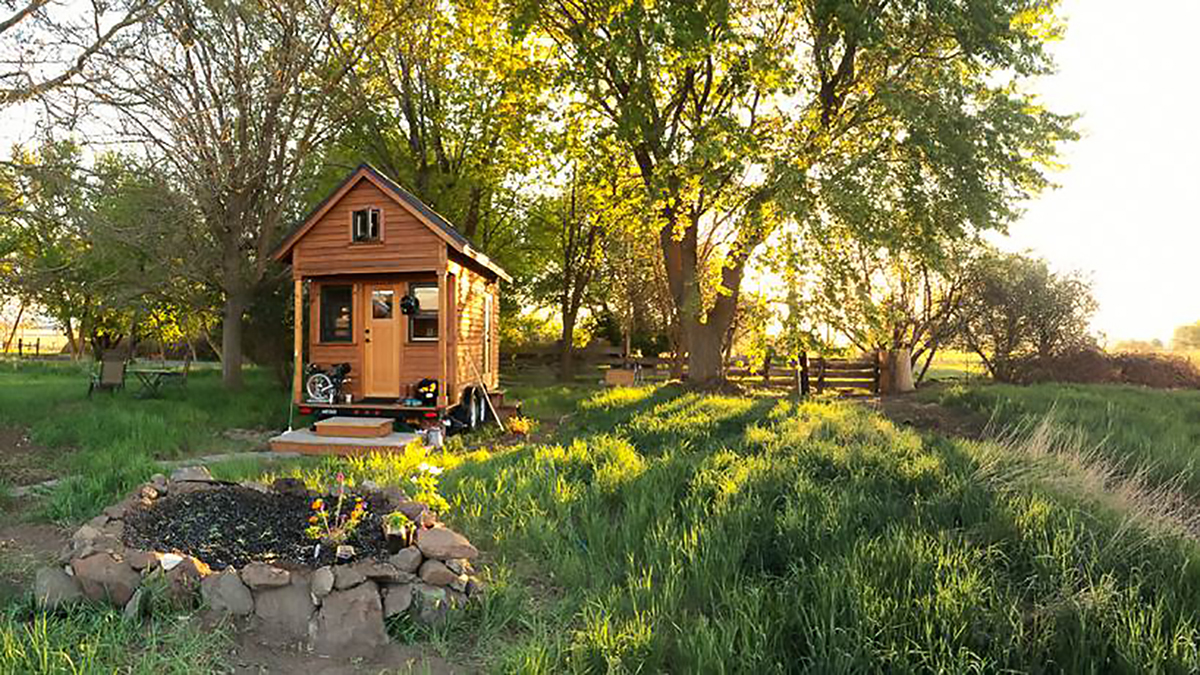

Minimalism, downsizing, tiny houses. Experiences above objects. Decluttering and simplifying your lifestyle. Over the past few years the idea that the road to happiness may actually be paved with less, not more, has become a first-world obsession for millions of people around the globe.

Anyone who’s ever cleaned out a closet or streamlined their investment accounts can attest to the effect. So is the secret to greater well-being found in simplifying and shedding possessions we no longer need? If so, why? What’s happening to us psychologically when we bag up all those shoes? And if decluttering is so good for you, why is it so hard? Why do we hang on to all this stuff in the first place?

A new paper out this week by Sarah Newcomb, a behavioral economist with Morningstar, offers some tantalizing insights into what’s going on here.

“Our sense of self includes things we have control over,” she says. That connection can run deep, especially when you tie a personal story to an object, and even when that object isn’t serving a useful purpose anymore. That bowl I no longer use was a wedding gift from my aunt; the chair no one sits in was my great-grandmother’s; my daughter’s dolls she rarely plays with anymore had been mine as a child. Everything is freighted with memory. Parting with things that remind you of good times or people you care about becomes difficult, because it actually feels like you’re paring down a part of yourself.

It isn’t just heirlooms and mementoes, says Newcomb. “Psychological ownership extends to things that you touch,” she says. If you were at a restaurant, and a waiter suddenly snatched away your glass of water, you might be “personally affronted,” since in your mind’s eye while you’re using that glass, it’s yours. Similarly, do you regard office furniture at work as “your” desk and “your” chair? This helps explain, too, why retail therapy is indeed a real effect. When we feel depleted or fatigued, acquiring something new can momentarily enhance our sense of self and boosts our identity, Newcomb says.

So if we’re tied so closely to things, why would paring back help increase our sense of well-being?

To find out, Newcomb surveyed U.S. adults, with varying degrees of wealth, how much “control” they felt over their financial lives, as well as whether they felt positively or negatively about their finances. She did not “measure how much control a person actually had in their financial lives, but how much they believed they had,” according to the paper.

“It is the feeling of power, not necessarily the exercise of it, that we found was linked to emotional well-being.” What she found is a strong correlation between a sense of power over choices in their financial lives and experiencing more positive feelings such as more joy, peace, satisfaction and pride.

The amount of money you had was not the most important thing, and the top earners she studied were not necessarily the happiest people. The standardized effect size of empowerment on emotional well-being was more than twice as large as income, according to the paper. In fact, those with higher salaries often reported feeling stress too, something she explains by pointing to the undeniable relationship between how bigger expenses require more upkeep.

Her conclusion: Identifying what is really necessary frees up more mental and emotional resources, enhancing a greater sense of well-being. It’s a logical connection given that many economic forces are indeed way beyond our control. Market moves, interest rates, the overall economy, our employers’ (or prospective employers’) hiring plans — the only thing you can actually choose is your own lifestyle.

“One of the benefits of scaling down is your maintenance costs are lower,” she says. “The more that you have, the more that you need to maintain.” Indulging in retail therapy too, while providing a temporary boost, comes with an even greater downside given that feeling fades quickly.

“What we need to understand is that the cost is permanent,” she says, “and the benefit is not.”

– Elizabeth Harris

This articles originally appeared in Forbes.com and is used for demonstration purposes only.