Why the Bible Doesn’t Stand a Chance Today

The 2002 film Reign of Fire portrays a post-apocalyptic world in which dragons have reawakened and established their dominance over the world.

Near the beginning of the film, Christian Bale and Gerard Butler’s characters do a dramatic portrayal of a scene from The Empire Strikes Back for a group of children who would have never had an opportunity to see the Star Wars series. They are able to act out the scene from memory.

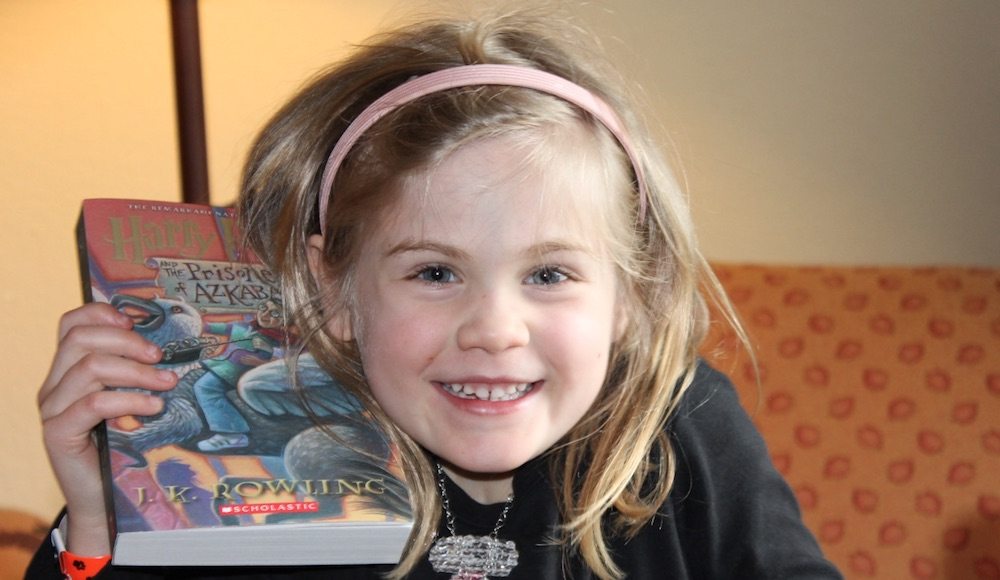

I’m confident that I, and many of you, would be able to do the same. I’m also confident that a large percentage of children in the Western world—including my own—could retell significant portions of Star Wars, Harry Potter, The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings, and The Hunger Games. These stories are ingrained on our memories as a result of repeated watchings, readings, conversations, quotations, and reminders from the retail industry in the form of t-shirts, toys, and posters.

Can Western culture today say the same for the Bible? Could most people who call themselves Christians do dramatic retellings, from memory, of scenes and parables from the Bible? Could their children? Do they actually do these retellings? Are these the stories that capture their attentions and imaginations, that they spend hours discussing with family and friends, that they think about before they fall asleep?

I don’t think so. Though the Bible still ranks as the most purchased book in the world over the past 50 years, and though snippets of it are heard in once-a-week church services and discussed in study groups, it has ceased to be part of the storytelling that influences the West’s mainstream culture.

And make no mistake: storytelling serves a crucial role in shaping a culture’s identity.

In his 1981 book A Community of Character, noted Duke University theologian Stanley Hauerwas argues that “every community and polity involves and requires a narrative,” and that this narrative—i.e., stories rather than abstract principles—is what shapes the ethics by which a community lives. The survival of the community depends on its ability to keep its stories alive as a source of meaning for its people, and “the loss of narrative [is] the loss of community.”

In Christ the Lord: Out of Egypt, novelist Anne Rice attempted to recapture what a culture—namely, first century Judea—might have looked like where the Bible was the primary narrative. The account below is told from the perspective of a young Jesus Christ, who is traveling home in a caravan with his family:

We all loved the stories of David and Saul. Even Silas and Levi who were usually bored with stories came up to listen as Cleopas told these tales. Cleopas was speaking in Greek all the while, and we were all very used to it, and liked it, though nobody said so.

Cleopas told us the marvelous story of how Saul, when the Lord ceased to speak to him, went to the Soothsayer of Endor, to beg her to summon from Sheol the spirit of the dead Prophet Samuel, to tell Saul his fate. There was to be a great battle on the next morning, and Saul, who no longer found favor with the Lord, was desperate, and sought out a woman who could talk to the dead. Now this was forbidden by Saul’s own orders, along with all soothsaying. But such a woman was found.

And out of the Earth by her power came the spirit of the Prophet asking, ‘Why have you disturbed my rest?’ Then he foretold that Saul’s enemies would defeat Israel, and that Saul and his sons would all die.

‘And what happened then?’ asked Cleopas, looking around at all of us.

‘She made him sit down and eat a meal for his strength,’ said Silas.

‘And that’s what we’d like to do right now.’ Everyone laughed.

When the Harry Potter series came out, I remember that a number of Christians opposed it on the grounds that it could stoke an unhealthy curiosity about magic in children, leading them to eventually dabble in harmful occult practices.

While not wishing to outright dismiss these concerns (personally, I just don’t know much about the occult and the supposed gateways to it), I thought that these Christians should worry more about Harry Potter usurping the place of the biblical narrative in their children’s lives than they should about its magic elements. The Bible, after all, does not have cool book covers. It does not have Lego sets. It does not have Halloween costumes that are sold in department stores. And it does not take place in a familiar setting (school) where today’s children spend forty-plus hours each week. When faced with an alternative such as Harry Potter, supported by a creative, attractive, visually-stimulating, multimedia onslaught, it’s difficult to see how the Bible can realistically compete for children’s attention.

It’s common for Christians today to issue calls for the restoration of a Christian culture in the West. If they really mean that, then, to make it happen, I think they would have to undertake a concerted effort to make the Bible the primary narrative that shapes their lives and the lives of their children. Practically speaking, they would have to spend more hours reading, thinking, and talking about the Bible than other entertainment alternatives. Otherwise, an authentically Christian culture cannot exist.

Ludwig Feuerbach famously wrote that “You are what you eat.” I think it’s also true that you are the stories you tell.

This column originally appeared at Intellectual Takeout and is reprinted by permission.