Sensible and reasonable people often disagree on the purpose of education.

As we’ve seen, men as renowned as Cicero and Benjamin Franklin believed the primary purpose of education was to build character and virtue in pupils. Moral education of this kind is likely to be palatable to most people—at least when a society enjoys general homogeneity in its values.

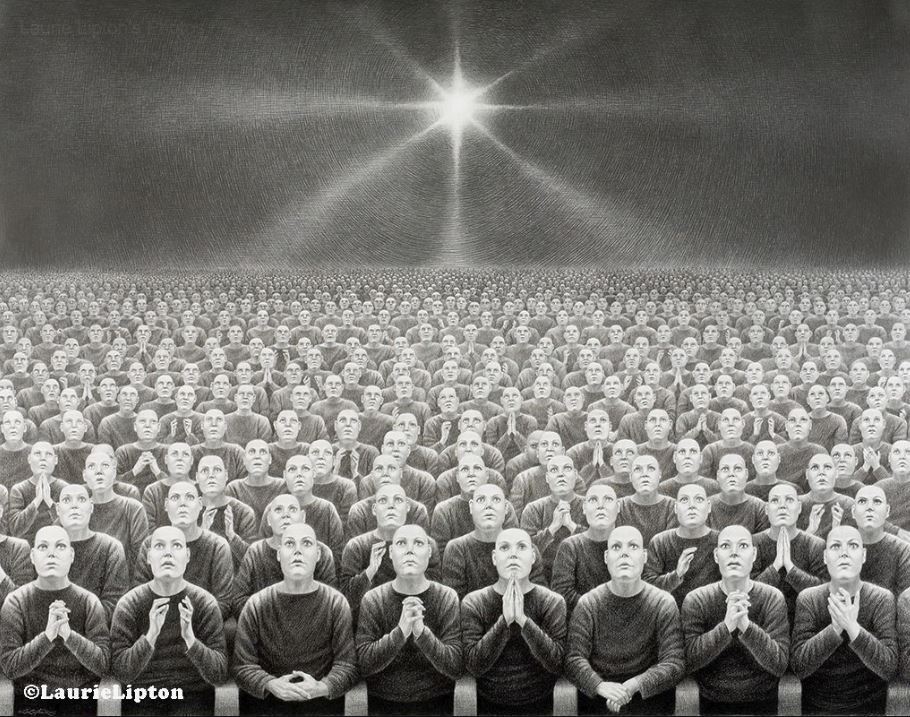

But there are reasons to be skeptical (and wary) of the values-driven education that we increasingly see in America’s public schools today, where many students are being taught a controversial social justice curriculum from a young age. An illustration of such a curriculum can be found in Aldous Huxley’s brilliant novel Brave New World.

Early in the novel, we see that the Directors were able to build their wonderful world of conformity and docility through a scientific breakthrough: sleep-teaching (or hypnopaedia).

“The case of Little Reuben occurred only twenty-three years after Our Ford’s first T-Model was put on the market.” (Here the Director made a sign of the T on his stomach and all the students reverently followed suit.) “And yet …”

Furiously the students scribbled. “Hypnopædia, first used officially in A.F. 214. Why not before? Two reasons. (a) …”

“These early experimenters,” the D.H.C. was saying, “were on the wrong track. They thought that hypnopædia could be made an instrument of intellectual education …”

(A small boy asleep on his right side, the right arm stuck out, the right hand hanging limp over the edge of the bed. Through a round grating in the side of a box a voice speaks softly.

“The Nile is the longest river in Africa and the second in length of all the rivers of the globe. Although falling short of the length of the Mississippi-Missouri, the Nile is at the head of all rivers as regards the length of its basin, which extends through 35 degrees of latitude …”

At breakfast the next morning, “Tommy,” some one says, “do you know which is the longest river in Africa?” A shaking of the head. “But don’t you remember something that begins: The Nile is the …”

“The – Nile – is – the – longest – river – in – Africa – and – the – second – in – length – of – all – the – rivers – of – the – globe …” The words come rushing out. “Although – falling – short – of …”

“Well now, which is the longest river in Africa?”

The eyes are blank. “I don’t know.”

“But the Nile, Tommy.”

“The – Nile – is – the – longest – river – in – Africa – and – second …”

“Then which river is the longest, Tommy?”

Tommy burst into tears. “I don’t know,” he howls.)

We see here that these early attempts of sleep-teaching failed. The Director explains that no more attempts were made to teach children the length of the Nile while they slept.

Why did they fail? They were attempting intellectual education on a passive subject. That doesn’t work.

You can’t learn a science unless you know what it’s all about.

“Whereas, if they’d only started on moral education,” said the Director, leading the way towards the door. The students followed him, desperately scribbling as they walked and all the way up in the lift. “Moral education, which ought never, in any circumstances, to be rational.”

Huxley’s point is that moral education requires no actual thinking. The recipients of hypnopaedia are not learning; they are being programmed. What type of moral education are they receiving? Huxley shows us:

A nurse rose as they entered and came to attention before the Director.

“What’s the lesson this afternoon?” he asked.

“We had Elementary Sex for the first forty minutes,” she answered. “But now it’s switched over to Elementary Class Consciousness.”

The Director walked slowly down the long line of cots. Rosy and relaxed with sleep, eighty little boys and girls lay softly breathing. There was a whisper under every pillow. The D.H.C. halted and, bending over one of the little beds, listened attentively.

“Elementary Class Consciousness, did you say? Let’s have it repeated a little louder by the trumpet.”

At the end of the room a loud speaker projected from the wall. The Director walked up to it and pressed a switch.

“… all wear green,” said a soft but very distinct voice, beginning in the middle of a sentence, “and Delta Children wear khaki. Oh no, I don’t want to play with Delta children. And Epsilons are still worse. They’re too stupid to be able to read or write. Besides they wear black, which is such a beastly colour. I’m so glad I’m a Beta.”

There was a pause; then the voice began again.

“Alpha children wear grey. They work much harder than we do, because they’re so frightfully clever. I’m really awfuly glad I’m a Beta, because I don’t work so hard. And then we are much better than the Gammas and Deltas. Gammas are stupid. They all wear green, and Delta children wear khaki. Oh no, I don’t want to play with Delta children. And Epsilons are still worse. They’re too stupid to be able …”

Instead of learning literature, history, art, logic, and philosophy—those are reserved for the rulers of this dystopia—pupils are indoctrinated with class-consciousness and banal slogans:

“Everyone belongs to everybody.”

“Even Epsilons are useful.”

And of course they receive their daily dose of soma.

Now, Huxley was writing a novel, of course. And, last I checked, sleep-teaching was not being used in our schools. Still, take a look at education today.

I ask you: Are today’s schools primarily teaching students to think? Or are they primarily programming them with certain values?

This column originally appeared at The Foundation for Economic Education, and is reprinted by permission.