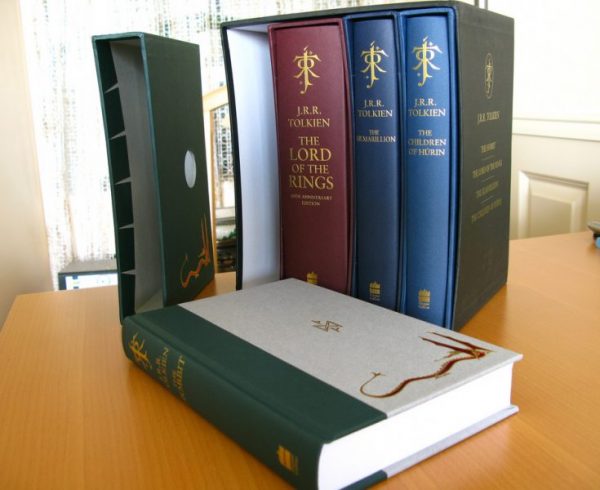

Editor’s Note: Author Matt Dickerson gives his interpretation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s stories of characters deciding to act either hostile or hospitable to strangers. Dickenson’s first part of the two-part series can be read here: Building Walls vs Giving Refuge; Reflections on Tolkien [Part 1]. The final part can be read below.

The Hobbit has numerous examples of hospitality—or lack thereof—which play significant roles in the narrative and have an impact on the outcome of events.

Time and again, acts of hospitality toward strangers, even when that hospitality involves risk or personal sacrifice, is portrayed by the author as virtuous and wise. The tale begins with the hospitality of the hobbit Bilbo to the dwarves, even though at the time the dwarves are strangers from another race.

The narrator is careful to point out that Bilbo’s hospitality may result in his own going hungry. The author also refers to this hospitality as a “duty”—a strong word in the text suggesting moral obligation. As I argued in my book A Hobbit Journey, it is Bilbo’s practice of this duty of hospitality toward strangers that trains him for the later acts that eventually define him as a hero.

Something could also be said about the hospitality of Beorn. Readers may note that Beorn is distrustful or resentful of visitors, and must actually be slowly lured into his hospitality. That is a fair assessment. It is also true, however, that Tolkien does not portray Beorn as a particularly virtuous character. He is brave and strong, but he is a character straight out of Norse myth who lives in a sort of pre-moral universe.

He is not evil, but neither is he really good. In any case, his generous hospitality itself is shown as good, and it is also important. His hospitality is a step in the direction that, in later years, will make him a great ruler of men.

But that leads us to the final example from The Hobbit. In contrast with the hospitality of Elrond, the elven king, Thranduil, and the folk of Mirkwood are much less hospitable to Thorin and his company. Though Thorin has done nothing wrong other than to show up among the Mirkwood elves needy and desperate, Thranduil captures the dwarves and treats them as prisoners. What is the reader to make of this?

Part of the answer again comes from the judgement of the narrator. Though at the confrontation before Thorin’s wall, the sympathies of Gandalf and Bilbo (and of most readers) fall on the side of Bard and the elven king rather than Thorin, the narrator is also quick to point out that Thranduil is not without his flaws.

Though the Mirkwood elves are not wicked, they are also described as “less wise” than the elves of Rivendell. Failure to show hospitality would seem to be one aspect of this lack of wisdom. Indeed, Thranduil is said to have a “weakness…for treasure, especially for silver and white gems; and though his hoard was rich, he was ever eager for more.” The narrator also points out that these elves had a “distrust of strangers,” and this distrust is described as a fault.

Thus, on the one hand it is true that the elves of Mirkwood fail to show hospitality to Thorin and his dwarves. This seems to come from a mix of distrust and desire for security, as well as some greed. But these reasons for lake of hospitality are the very points about which the narrator is critical of Thranduil. They are weakness and faults. More importantly, perhaps, is the outcome of the inhospitality of these elves.

In their failure to welcome the refugees—their decisions to lock up in a dungeon the lost and starving dwarves rather than giving them food or aid—they perpetuate the ancient hostilities, and help make a world in which distrust rather than hospitality is the norm. In short, this act of the elves becomes one of the very things that leads to the inhospitality of the dwarves toward the end of the tale, when Thorin decides to build a wall rather than aid the folk of Laketown.

Still, neither Gandalf nor the narrator excuse Thorin any more than Thranduil. And if we turned from The Hobbit to The Lord of the Rings or other works of Tolkien’s Legendarium such as The Silmarillion, we could find an abundance of further examples. We could speak of Galadriel and how she breaks down the ancient racial hostilities by welcoming the dwarf Gimli into her kingdom, and how that act of hospitality changes the whole course of the Fellowship, the life of Gimli, and ultimately the future of many kingdoms.

Or we could look at how Saruman comes to the Shire and corrupts it, so that instead of the returning hobbits finding a warm welcome in an inn, they are locked out by a “great spiked gate”—a newly built wall, as it were, designed to keep out strangers. And along with the new wall are new rules prohibiting “taking in folk off-hand like and eating extra food.” This is part of the new evil that the four hero hobbits return to discover, and eventually must work to undo.

That undoing of the work of Saruman—the breaking down of walls and spiked gates, ending rules that prohibit hospitality; the choice to show hospitality to aliens and strangers and refugees, turns out to be the real work of Tolkien’s heroes.

Very interesting read, thank you.

How would you situate this idea that “open hospitality is indicative of wisdom” in the broader mythology of Middle Earth, where the most high elves of Doriath and Gondolin lived in hidden kingdoms that allowed none (or rather precious few) to even enter? The few mortals shown hospitality like Tuor and Turin not only are the exception, but also have some standing with the elves due to lineage.