The best art and literature is timeless. Writings can explore the deepest levels of human nature and experience. They remain culturally relevant far beyond the spatial and temporal context of the particular culture from which they emerged.

The best literature is transcendent.

This is certainly true of the writings of J.R.R.Tolkien, especially his Middle-earth Legendarium. I was reminded of this yet again when I recently reflected on how often in his stories Tolkien contrasts the showing of hospitality toward strangers (giving refuge) with the building of walls to keep them out.

The passage that started me thinking about this is was from the end of The Hobbit. When the dragon Smaug is killed, Thorin Oakenshield finally claims the kingdom of Erebor and the throne at the Lonely Mountain. One of his firsts acts as ruler (after examining his tremendous new wealth) is to build a wall to keep others out. “So now they began to labour hard in fortifying the main entrance, and in making a new path that led from it… the gate was blocked with a wall of squared stones laid dry, but very thick and high.”

Of course, there is nothing unusual about a king building a castle with walls. It’s an important part of the defense of a kingdom. What is noteworthy about this wall is whom Thorin is working so desperately to keep out. He is building a wall to keep out folk of other races (namely men and elves), and in particular to keep out the refugees resulting from a recent devastating war.

The men of Laketown have just had their town destroyed by a dragon. If you haven’t read the scene, just think of hours of airstrikes raining fire down from the sky, until not a building stands and nothing is left but ruin and destruction. The Laketown folk have lost family and homes, food and livelihood, and indeed their very hopes for the future. Worse yet, this happens at the onset of winter. They face terrible hardship of starvation and freezing. These are the desperate and needy folk Thorin is trying to keep out.

This is a rather stark contrast, since only a few weeks early Thorin and his company showed up at Laketown as strangers of another race, hungry, needy, sick, and in desperate need of aid. The people of Laketown took them in, fed them, and provided generous aid.

These are the people Thorin is building a wall to keep out. To make matters worse, the suffering of the Laketown folk is due largely to Thorin’s own actions. Though Thorin himself did not destroy the town, in his desire for gold and treasure he did wake up and anger the sleeping dragon Smaug.

Smaug attacked Laketown to take revenge for Laketown aiding the dwarves. As the wise old raven Roäc tells Thorin, “By the lake men murmur that their sorrows are due to the dwarves; for they are homeless and many have died, and Smaug has destroyed their town.”

Politics is never quite this simple, of course. There also happens to be an army of elves from Mirkwood alongside the men outside of Thorin’s newly built wall. (Unlike the dwarves, the elves actually came to the aid of the Laketown refugees, but that’s another story.)

The men and elves do show up at the doors of Thorin’s castle bearing arms. Thus Thorin can claim some justification in building a wall for his own defense. What it really comes down to in the end, however, is wealth.

Thorin and his followers are now exceedingly wealthy, and they have no intention of sharing any of that wealth with war refugees of other races no matter how needy those refugees are, and no matter what aid the people of Laketown had given them earlier. Again, Roäc the raven sees this clearly. “We would see peace once more among dwarves and men and elves after the long desolation; but it may cost you dear in gold.”

In any case, whatever justification Thorin may claim for building his wall and refusing aid to the refugees, Gandalf—Tolkien’s clearest figure of wisdom in the book—thinks poorly of it. His judgement spoken to Thorin is simple and telling. “You are not making a very splendid figure as King under the Mountain.”

We see Thorin’s wall-building in an even starker light when we contrast it with the earlier hospitality of Elrond. When The Hobbit begins, Thorin and his own people are the refugees. They had been the victims of Smaug’s earlier attacks when he sacked and burned Erebor, and then occupied it.

Thorin’s family, led by his grandfather Thrór, became homeless wanderers—refugees of war—to the point where Thrór, a once powerful and wealthy king, was “old, poor, and desperate.” After Thrór’s death, his grandson Thorin and his people continued to live as exiles in foreign countries, taking whatever labor they could find. Though Thorin was an heir to a throne, he was “an heir without hope.” Even when his hard labors eventually provide some wealth, he still speaks of his halls as “poor lodgings in exile.” In short, he is one who might have been expected to understand compassion for the outcast, the refugee, the exile.

In this condition—as a longtime exile, refugee from a past war, bereft of his father and grandfather—Thorin and his company come to Rivendell in need of aid from the elven king Elrond. They also happen to be hungry and tired from a long journey and a run-in with trolls.

What Elrond gives them is warm welcome, generous hospitality, and aid. “And so at last [the dwarves] came to the Last Homely House, and found its doors flung wide… All of them, the ponies as well, grew refreshed and strong in a few days there. Their clothes were mended as well as their bruises, their tempers, and their hopes. Their bags were filled with food and provisions.”

This hospitality is notable for several reasons. First, Elrond certainly had the power to keep them out, as readers of The Lord of the Rings will remember (from the attempt of the Ringwraiths to enter Rivendell.) In other words, Elrond could easily have had a wall if he needed one—if he chose to use his power to raise one up. What he had instead were “doors flung wide.”

Second, the dwarves are not only of a different race, but they are of a race with a long history of conflict and animosity toward the elves. Elrond is descended from the elven kingdom of Doriath which was destroyed centuries earlier by the dwarves. This ancient animosity is referenced repeatedly throughout Tolkien’s writing.

Third, Thorin and his dwarves have different values and a different history than Elrond and his people. As the narrator points out, Elrond “did not altogether approve of dwarves and their love of gold.” They are races with different cultures, different practices, different values. Today, one might say they were of different religions. Nonetheless, Elrond welcomes them. He doesn’t affirm their beliefs, but he does offer refuge and aid to the refugee. He does this despite the risk to himself and his people.

It is clear that Elrond’s approach—his choice to show hospitality to the stranger rather than to build a wall to keep out the foreigner and refugee—is the approach Tolkien associates with wisdom. The narrator’s first description of Elrond tell us that he is noble, fair, wise, and kind.

Editor’s Note: The above commentary is the first of two parts.

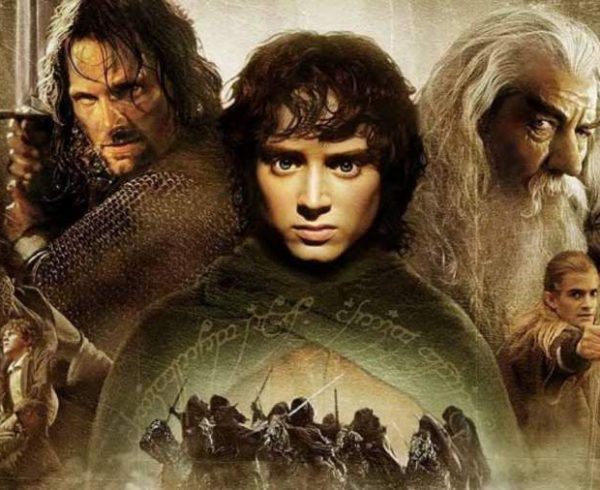

Main photo above: The Hobbit Movie Facebook Page