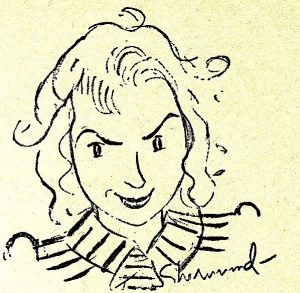

![]() It’s so much fun to discover an artist whose work I haven’t known before. This happened again last weekend at an antique show in Houston where one of the dealers had some wonderful original cartoons by Barbara Shermund. Of course I wanted to learn more about this talented woman, who could draw so well but also wrote her own gags.

It’s so much fun to discover an artist whose work I haven’t known before. This happened again last weekend at an antique show in Houston where one of the dealers had some wonderful original cartoons by Barbara Shermund. Of course I wanted to learn more about this talented woman, who could draw so well but also wrote her own gags.

Shermund started working at The New Yorker just 4 months after the magazine was founded. She was only 26 years old! Within months, she had designed her first cover, this highly stylized image of a modern young woman gliding along in the night. Her bobbed hair is blowing, while she confidently dozes, her profile framed by the twinkling stars. Does her nose remind you of Mrs. Gautreau’s in Sargeant’s Portrait of Madame X?

Shermund started working at The New Yorker just 4 months after the magazine was founded. She was only 26 years old! Within months, she had designed her first cover, this highly stylized image of a modern young woman gliding along in the night. Her bobbed hair is blowing, while she confidently dozes, her profile framed by the twinkling stars. Does her nose remind you of Mrs. Gautreau’s in Sargeant’s Portrait of Madame X?

Shermund came from an artistic family- her dad was an architect and her mom was a sculptor. She was born in San Francisco in 1899 and started drawing when she was little. She studied at the California School of Fine Arts before heading the New York.

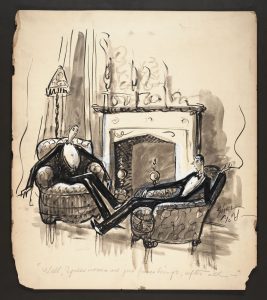

Barbara Shermund, “Well, I guess women are just human beings after all,” Ink on paper, n.d., Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum

Shermund once told Collier’s Magazine that her visit became a long time residence “after she had eaten up her return fare.” She had a hard time settling down, staying with friends and traveling with no permanent address until later in life. She was able to make her drawings anywhere, often working at someone’s kitchen table.

Barbara was so focused on creating her one-liners that she slept with a pencil and pad under her pillow in case she thought of an idea during the night. Later she bought ideas from gag writers.

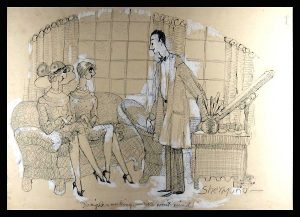

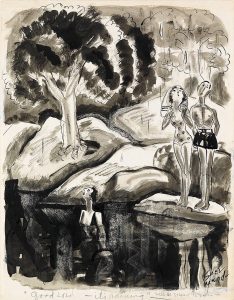

Barbara Shermund, “Go right on working – We won’t mind!,” ink on paper, for the New Yorker Magazine, June 4, 1927 issue.

New Yorker cartoonist Liza Donnelly describes Barbara Shermund’s technique in her book, Funny Ladies: The New Yorker’s Greatest Women Cartoonists and Their Cartoons.

Shermund experimented with her style, although her drawings were predominately strong and forceful. She was classically trained, and she displayed bold loose lines and an assuredness not dissimilar to her contemporary Peter Arno. Her energetic brushwork and dark grey washes are as gutsy as her captions. Hence the art and the words work together well.

She worked on large twenty-four-by- thirty-six-inch pieces of heavy, rough watercolor paper, first sketching out an indication of where the drawing would sit on the paper then boldly painting over the light pencil lines (the lines were merely guides). Sometimes her brushwork- it appears that in her early work, she did not use pen but rather a brush- was wet and potent, sometimes dry and sketchy.

In a letter from Shermund to her friend (and fellow cartoonist) Eldon Dedini, she wrote, “I have done a drawing as many as twenty times to get all the stiffness out of it and make it look as though I tossed it off in two minutes.”

Barbara Shermund, “Good Lord, it’s raining,” Ink and wash cartoon on paper. 17.5 x14″, Likely submitted to The New Yorker. Circa 1940.

This sounds a lot like the lines from William Butler Yeat’s poem, Adam’s Curse:

A line will take us hours maybe;

Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought,

Our stitching and unstitching has been naught.

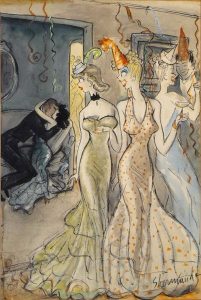

Barbara Shermund, “Now these are just what Madame needs- they’ll give her character,” Ink on paper, n.d.

Barbara Shermund was like a sponge, soaking up ideas for gags from the times and the people around her. She depicted the contradictions in all of us, but especially women sorting out the heady new freedoms of the early 20th century. Her women were both ditzy and bright, dependent and independent, tough and soft. They were thin, glamorous, smoked cigarettes, drank cocktails, frequented parties, beauty salons and department stores, and discussed dating, marriage and sex.

Co-founder of The New Yorker, Harold Ross, once said his magazine was “not for the old lady of Dubuque.” Back then you could open the New Yorker and read Herman J. Mankiewicz, Alexander Woollcott, James Thurber, Dorothy Parker, and Ring Lardner. Lewis Mumsford wrote a column on architecture. Janet Flanner reported from Paris on luminaries like Josephine Baker, Henri Rousseau, Edith Piaf and Jean Coucteau.

Barbara Shermund, “He’s the gentleman who came up to complain about the noise!” (study for Esquire), 1950–1959

Shermund worked at The New Yorker until 1944, eventually publishing 597 drawings and supplying 8 covers. Esquire published her cartoons into the 1950s as did King Features. In 1950, Barbara Shermund became one of the first three women to be accepted as a member of the National Cartoonist Society.

In 1947, Irving Penn photographed eighteen New Yorker cartoonists for the August 1947 issue of Vogue. Charles Addams is reclining on the platform. Saul Steinberg is sitting in front. And Barbara stands out among all of them in her chic black dress and dark wide brimmed hat.

Barbara Shermund never married. A free spirit, she lived alone during the last years of her life in a little house on the coast of New Jersey. She died in September 1978 during the newspaper strike. How ironic that the New York Times could not run a full obituary on someone whose life’s work had been producing things for print.

If you want to read more about Barbara Shermund and other lady cartoonists, check out Liza Donnelly’s book, Funny Ladies: The New Yorker’s Greatest Women Cartoonists and Their Cartoons.