Exclusive SCENES Interview With Director David L. Cunningham

There was literally no logical reason for David L. Cunningham to get into filmmaking. A quick dive into his background proves that statement to be anything but hyperbole. When Cunningham was a kid, the likelihood that he would become a missionary, a preacher, or the head of a non-profit organization was a statistical lock.

Need evidence? Look no further than the seven generations of ministry on one side of his family, and the four generations of ministry on the other side. Cunningham’s great grandfather started 13 churches out of a covered wagon in Oklahoma when it was still a territory. His great uncle was a prisoner of war in World War II at the hands of the Japanese because he stayed with the church he started there. His grandmother was the first ordained female minister in her denomination.

And finally, his parents, Loren and Darlene Cunningham, started an interdenominational organization called Youth With A Mission (YWAM).

“So the family business is clearly in the ministry and as a young 12-year old guy, I just knew that I was supposed to be making movies,” Cunningham explains. “It was so out of the blue for my context. I grew up traveling the world with my folks in mostly not a lot of glamorous places—refugee camps and places where there was a lot of need. Growing up on the outer island of Hawai’i, we lived in a place that was isolated and had just one cinema – which was pretty funky at the time. I wasn’t around movies much at all.”

But there was a problem. Cunningham didn’t have any role models to follow. There were no mentors around who could take him under their wing. The primary faith-based films at the time were from iconic Christian evangelist Billy Graham.

“Do you think you’re supposed to be making Billy Graham movies?” his dad asked.

“No,” Cunningham replied. “I think I’m supposed to be making Hollywood movies.”

More than 30 years later and his filmography reveals every kind of production imaginable—short films, documentaries, TV mini-series, and yes, major Hollywood movies. The journey to success, however, was anything but easy, and at times caused him to wonder if the entertainment business was the right career path after all.

From Hawai’i To Hollywood (And Beyond)

After high school, Cunningham did the most logical thing any aspiring director might do at the time—he went to USC Film School. While there, he certainly learned a lot of helpful things in class, but the real education took place in his dorm room closet where he and his roommate set up a makeshift production studio. The duo produced wedding videos, Taiwanese karaoke videos, adventure shows, documentaries, and (in the earliest days) a stakeout video for a printing company seeking to identify loiterers from a nightclub across the street.

Cunningham’s more adventurous moments came in places like the Australian outback, the African Sahara, and Pitcairn Island where he sailed for a week from Tahiti to bring the remote island’s first American film crew. At the age of 25, he ran a company with eight fulltime people and a studio in Los Angeles, but he was moving further away from his true calling.

“I knew I needed to do a significant pivot to get on track with my passion of narrative storytelling,” Cunningham recalls. “So I went around to everyone who would listen and gave my version of the Jerry Maguire speech where he makes a passionate pitch to start his own agency. It was crickets. A lot of people liked what we were doing and couldn’t believe I would risk everything to make an independent movie.”

Thankfully for Cunningham, he had his own Renee Zellweger to support his dream—his wife of six months, Judy. She got a job as a waitress at a Mexican restaurant. They rented out their apartment and slept on a friend’s floor. He dusted off his American Express card and flew around the world to raise money.

“I figured no one person would fund a first time filmmaker with a lot of money but maybe a lot of people would fund me for a little bit,” Cunningham says. “This was in the late 90s, pre-crowd funding. I was right out of film school and even though I had a degree and all of this experience in other categories, you’re not really a moviemaker until you’ve made a movie. You’re first film is really your film school—no matter how many courses you take, how many short films you make. You’ve just got to do it.”

In a year’s time, he had raised $750,000 from 27 investors in six countries. The resulting product was Beyond Paradise, which was about a coming-of-age story about a white kid and his three Hawaiian friends.

“That journey was grueling and enlightening on how tough it is to make movies,” Cunningham says. “It took about a year to get the film made and another year to get it marketed. It was a three-year process. Everything that could go wrong through the entire process went wrong. There were lots of reshoots. Distribution deals fell through. I just wanted to make films but realized I was going to have to understand and learn the whole process if this was going to be my life career.”

The 9/11 Dilemma

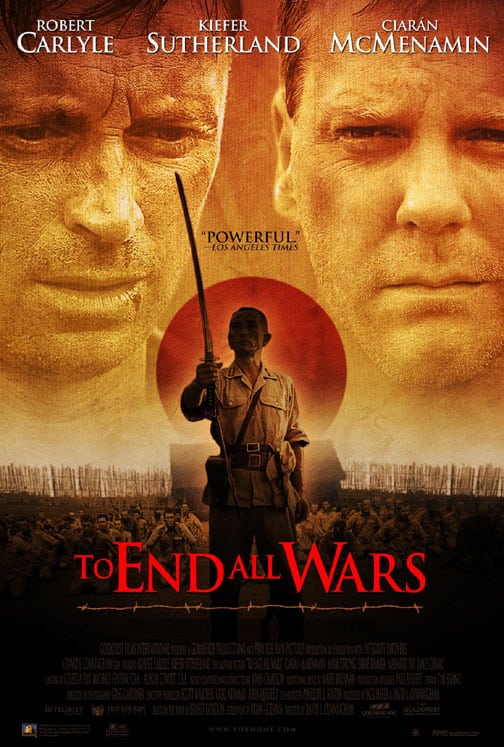

Cunningham’s next step was more like a gargantuan leap. One of his investors on Beyond Paradise helped him raise $10 million for a World War II flick called To End All Wars, which landed A-lister Kiefer Sutherland. The film debuted at the Telluride Film Festival in Colorado and, despite two less than desirable screening scenarios, drew favorable attention from Universal, Walden Media, and representatives from Steven Spielberg’s group.

Cunningham’s next step was more like a gargantuan leap. One of his investors on Beyond Paradise helped him raise $10 million for a World War II flick called To End All Wars, which landed A-lister Kiefer Sutherland. The film debuted at the Telluride Film Festival in Colorado and, despite two less than desirable screening scenarios, drew favorable attention from Universal, Walden Media, and representatives from Steven Spielberg’s group.

Over the course of a few hours, the paradigm had completely shifted in Cunningham’s favor. Fundraising was no longer a problem. Access to big name talent and powerful executives was being granted. Opportunities were coming in from everywhere imaginable. Life was good.

To End All Wars was set for a red carpet event on September 13, 2001, at the Toronto Film Festival—in Kiefer Sutherland’s hometown, no less. History had other plans. Two days earlier, a pair of hi-jacked planes infamously hit the World Trade Center towers and sent the nation reeling. The film festival was evacuated and cancelled. When the dust settled, all of the significant deals Cunningham had on the table went away.

“People didn’t want anything to do with war,” he says. “Fans of the film were saying we needed To End All Wars. It was talking about the opposite spirit of war. With all of the anger and hatred going on, we needed it for the cultural discussions. But the executives wanted romantic comedies now. They wanted escapism.”

Instead of a wide release, the movie was reduced to a limited release. And even though the film was ultimately good for his career and created many opportunities, Cunningham was left wondering what might have been.

“I was disappointed but grateful for having been put on the map as a studio director. But then, I had my first two studio gigs blow up after millions spent.”

The first movie backed by a well-known billionaire, who was a fan of To End All Wars, fell apart because of high profile corporate merger.

“It kind of blew my mind,” Cunningham says. “How does this happen when you have one of the wealthiest men in the country behind this? I thought that the most fragile part of filmmaking was the independent financing side of things. But no. I had this revelation that the studios can also be fragile and difficult.”

The second film Cunningham was attached to direct was torpedoed by the now infamous Harvey Weinstein.

“Weinstein had a competing movie with a similar story line as ours,” Cunningham says. “He made some kind of back office deal with our studio boss and our project and crew was immediately canned.”

Ironically, the historic event that negatively impacted his first significant film was the subject of a mini-series that ABC hired him to direct five years later. The Path To 9/11 had a $43 million, a cast of 200, was shot all over the world (New York City, Los Angeles, Toronto, Morocco, etc.) and was based on the non-partisan work The 9/11 Commission Report.

ABC and its parent company DISNEY spared no expense on accuracy. Cunningham had numerous advisors including a CIA operative who was first on the scene in Pakistan after 9/11, the man who held the launch codes for President Bill Clinton, and FBI anti-terrorism experts. ABC executives were excited about the final product. The two-night event was predicted to score critically and with audiences around the world.

But after the first showing at the National Press Club in Washington D.C., representatives from the Clinton camp approached writer/producer Cyrus Nowrasteh and voiced their displeasure over one particular aspect of the film.

“Everything went very fast after that,” Cunningham explains. “But essentially, they felt that the way we showed how the Clinton administration handled Osama Bin Laden was done in an unfair light that was political and with an agenda to keep Hillary out of the presidency. We were all flabbergasted. Most of the executives at ABC and Disney are Clinton supporters—the producers as well. I’ve never considered myself a political person although they made me one after that. But there was no agenda.”

That didn’t stop bloggers from attacking the film ahead of its release. On one front, they suggested that Nowrasteh (a registered Libertarian) was a conservative pundit bent on hindering Hillary Clinton’s chances to win her 2008 Presidential run. On the other front, naysayers pointed out Cunningham’s ties to YWAM and erroneously claimed that the evangelical ministry had funded the film, also in an effort to derail Hillary Clinton.

Mainstream news organization began reporting the blog posts as fact, which led to death threats, FBI involvement, and negative pontificating from government officials such as U.S. Senator Harry Reid.

Ultimately, ABC edited the footage in question and the film was released as planned. Although the numbers weren’t as big as projected, the mini-series did garner 23 million viewers between both nights and won a Prime Time Emmy.

“I was so naïve before that process,” Cunningham says. “I would watch the news and I would see Wolf Blitzer or whomever and assume that whatever was coming out of his mouth someone had vetted and he was speaking with authority. And I’m sitting on the couch with my remote in my hand and I see him saying lies about me and my family.”

A Hawaiian Homecoming

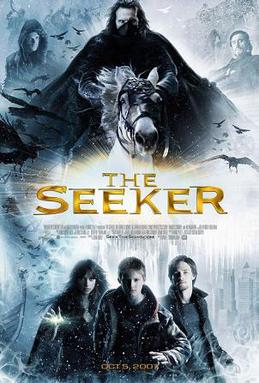

Despite the controversy surrounding The Path To 9/11, Cunningham remained a hot commodity in Hollywood. His next film was the Walden Media release The Seeker: The Dark Is Rising, which grossed $31 million worldwide. But even in the midst of success, something didn’t feel right.

Despite the controversy surrounding The Path To 9/11, Cunningham remained a hot commodity in Hollywood. His next film was the Walden Media release The Seeker: The Dark Is Rising, which grossed $31 million worldwide. But even in the midst of success, something didn’t feel right.

“I was sitting at the Fox lot having survived these studio movies and independent movies and still in my mid-30s at the time,” he recalls. “I had everything that all of these people were fighting for. I had the bungalow. I had the studio deal. I was up for a really big franchise film. I had the little golf cart. I had all of it. But then I had this revelation. I was looking at the big fancy gate at 21st Century Fox and seeing all of the security as all of the people are trying to enter into the gates. And I just had this feeling come over me that these guys are trying to break into a prison.”

“Don’t do it! Don’t do it! Turn around!” he instinctively thought.

Then, he prayed.

“Lord, I know I’m supposed to be a filmmaker. It’s my passion to tell stories. But there’s got to be another way to do this.”

Cunningham’s next move surprised everyone. He decided to go back to his roots and take the lessons learned from his indie and studio journeys home to Hawai’i. Everyone thought he was crazy. There was no way his storied career could survive such a radical move. But Cunningham had something different in mind—he wanted to raise his children in the same richly diverse environment he had experienced as a kid.

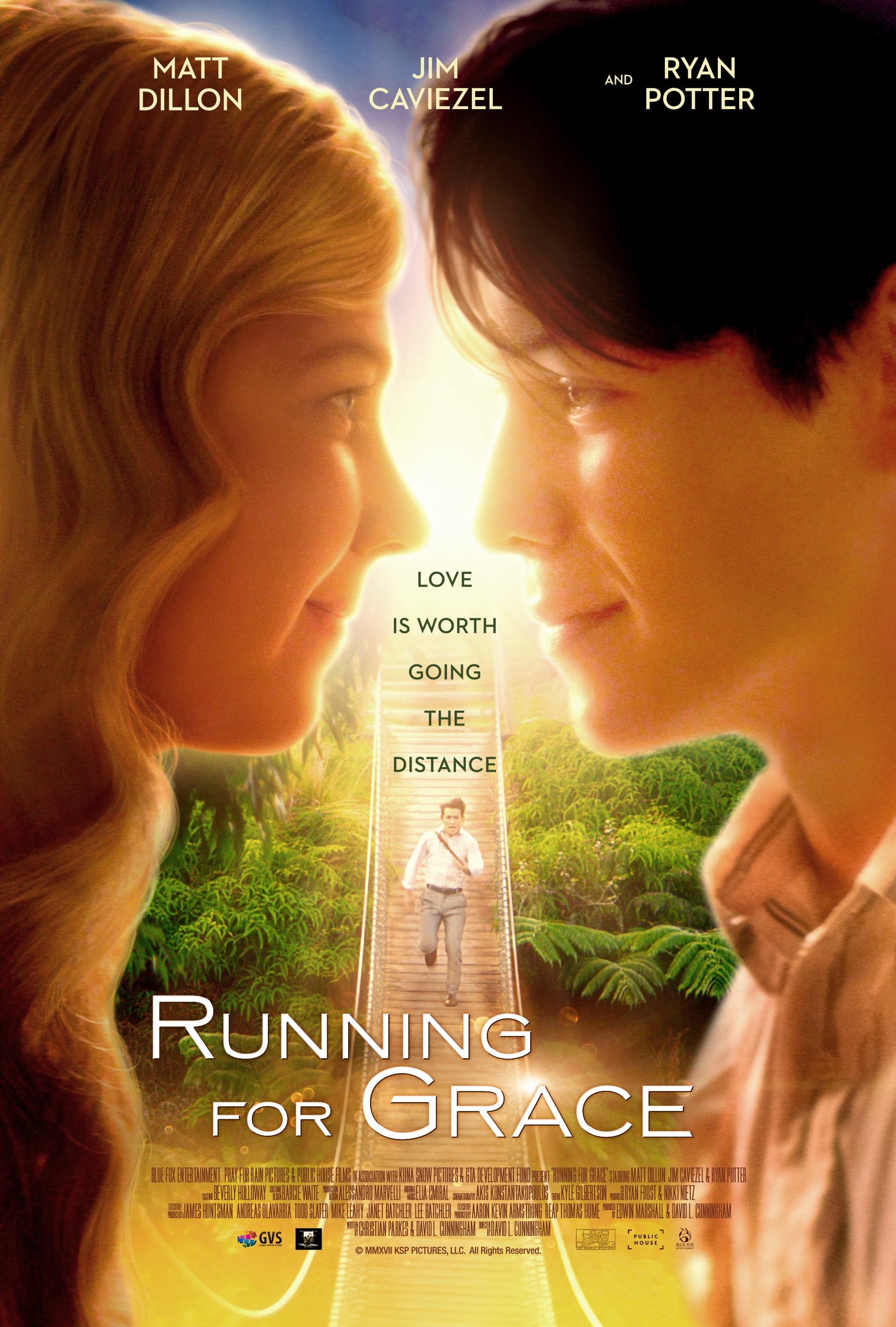

Now, after several years of hard work, he is releasing Running For Grace, his first film through the Hawaiian-based Honua Studios. It’s a smaller, independent film, but the cast is dotted with big name stars such as Jim Caviezel (The Passion of the Christ), Matt Dillon (Crash), and rising star Ryan Potter (Big Hero Six.)

“Jim can do anything,” Cunningham says. “People have short memories, but when you start reflecting on his filmography, he has played a tremendous range of characters over the years. I found him really entertaining to watch. I believe the audience will as well. Matt was also so genuine and engaged, and Ryan’s got that charisma and charm. It was a fun ensemble.”

Set in the 1920s, Running For Grace tells the story of a young orphan boy named Jo (Potter) who is half Japanese and half white. Rejected by all sides during an age of segregation, a new plantation doctor (Dillon) takes him under his wing and trains him to be his assistant. Jo’s forbidden love with the plantation owner’s daughter Grace (Olivia Ritchie) creates the conflict that will either bring together the community or tear it apart.

Set in the 1920s, Running For Grace tells the story of a young orphan boy named Jo (Potter) who is half Japanese and half white. Rejected by all sides during an age of segregation, a new plantation doctor (Dillon) takes him under his wing and trains him to be his assistant. Jo’s forbidden love with the plantation owner’s daughter Grace (Olivia Ritchie) creates the conflict that will either bring together the community or tear it apart.

“We tried to make a film that celebrates who you are,” Cunningham explains. “There’s a lot of discussion in popular culture about diversity. What you look like should be secondary to who you are. I grew up as a minority as a “haole,” as a white kid, with all of my friends being native Hawaiians. That was a real gift to have that perspective.”

Another goal of the film was to highlight the state of Hawai’i as an independent film hub.

“We believe that we have the talent, the locations and the proximity to do so,” he says. “This is the first film coming out of our shop to demonstrate that. We wanted to show people that Hawaii is more than just a location for pretty beaches and jungles.”

But ultimately, Cunningham found inspiration for the film when looking around his living room. His daughters loved comedies. His wife loved chick flicks. His son loved action movies. Was there a way to bring all of those elements into one movie?

“I think so,” Cunningham says. “We’re really proud of it. We hope people will get behind the film. Even though it’s a small film, we believe it can connect to a wide audience.”

Running For Grace releases in multiple theaters in Hawai’i (Kona, Hilo, Honolulu, Maui) on July 20th, and then in limited theaters across the United States on August 17th. The film will then be released to various on-demand and streaming platforms including iTunes.

Moving forward, he hopes to grow support for his own production house, Global Virtual Studio (GVS), which represents what he calls a “massive leap of faith” that seeks to find a happy medium between the two worlds in which he has spent the better part of three decades.

“I describe independent films as a beat up jalopy,” Cunningham explains. “You own it, and it gets you to the destination, but you break down a lot and it takes a lot longer to get there. Studio films, on the other hand, are like a Ferrari. The car pulls up and they throw you the keys. You’re all stoked to have horsepower and it looks great, but you get in the car and realize there are 20 people in the backseat telling you how to drive. You can’t fully engage the full potential of that vehicle because you’re stopping and going and grinding the gears.

“With GVS, we want to build a Mustang,” he adds. “It has some horsepower. It’s got some style. But it’s yours and you have autonomy to go where you want to go and do what you want to do.”