Last night I finally forced myself to listen to Marc Maron’s 2011 interview with Anthony Bourdain. I say finally because I’ve been putting off reading about or listening to anything involving Bourdain since I found out about his death by hanging on June 8th.

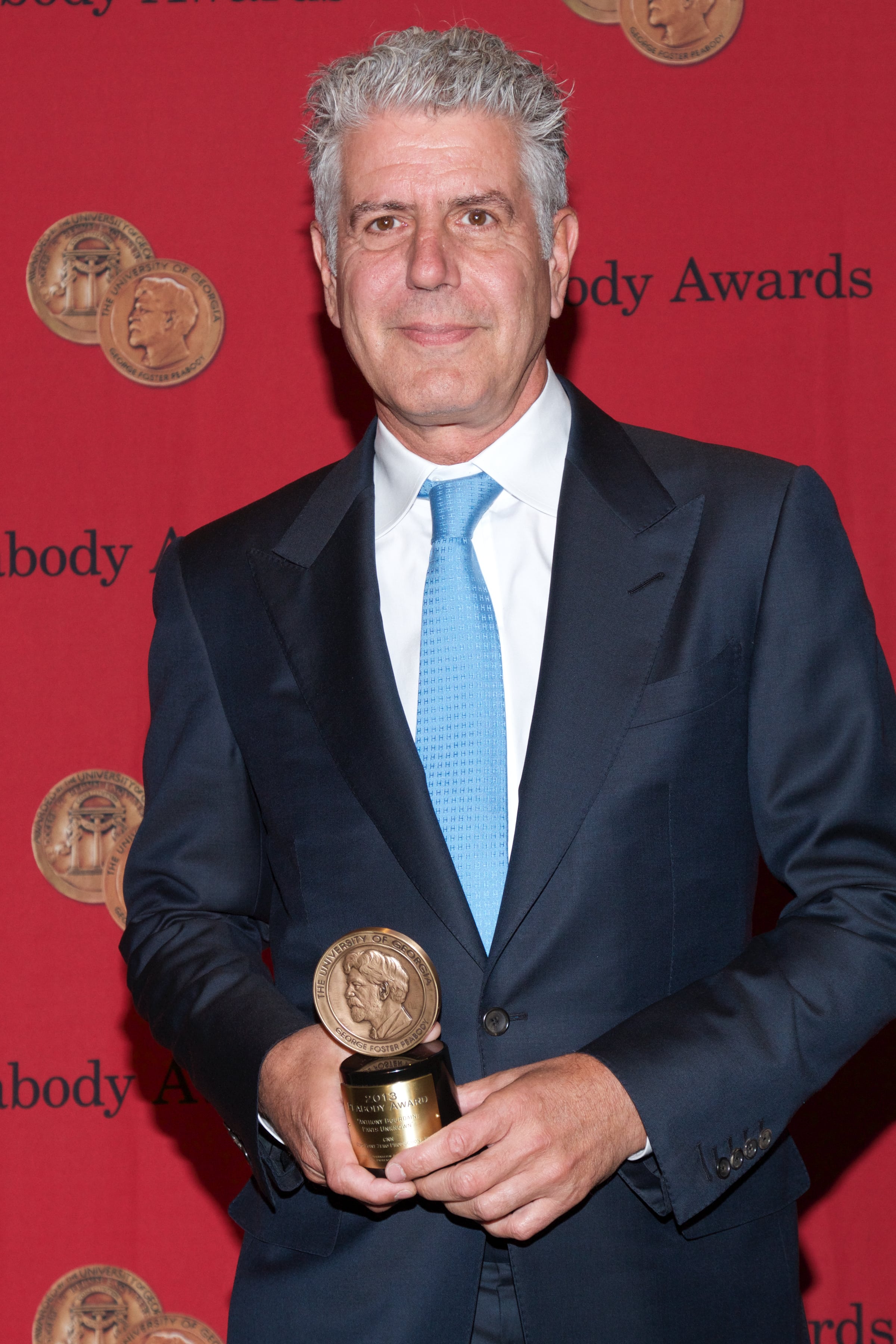

Bourdain was one of my heroes. I got to meet him a few years ago when he came to Oxford, Mississippi, to film an episode of his CNN show, Parts Unknown. He was so nice, and friendly enough to take a picture with my husband. I didn’t get a photo with him because I was too afraid of nerding out, fangirl that I was.

I’m a total foodie. I’ve been cooking since I could walk. My grandmother is a chef, and I grew up on the Mississippi Gulf Coast surrounded by great cooks who were focused on New Orleans-style French Cuisine. There’s a picture of my siblings and I at Thanksgiving in matching outfits, shucking oysters before we should have been allowed to hold a knife. Ah, the good old days, before helicopter parenting. But, I digress.

I first became aware of Anthony Bourdain when his debut book Kitchen Confidential came out to rave reviews. If you cared about food, you read that book. Those of us in the restaurant biz went crazy over it. He was one of us. He got it. The long hours, the sex, the drugs, the booze and the thousands of cigarettes smoked were something that hit home with us. He was a working chef, not some fancy celebrity. Bourdain was someone we could relate to.

I first became aware of Anthony Bourdain when his debut book Kitchen Confidential came out to rave reviews. If you cared about food, you read that book. Those of us in the restaurant biz went crazy over it. He was one of us. He got it. The long hours, the sex, the drugs, the booze and the thousands of cigarettes smoked were something that hit home with us. He was a working chef, not some fancy celebrity. Bourdain was someone we could relate to.

When he did become famous—from the success of that book, the books that followed, and the eventual TV shows—we didn’t leave his side. He was still raw, on-camera and off, and kept it real. He was a fan of punk rock, and loved the same bands I did, like the New York Dolls and The Dead Boys. He was a real New York City ragamuffin and the raconteur we had been waiting for. And he had cool parents. His dad was French and his mother was an editor at The New York Times. He was well-rounded and cooler than any of us. He was who we all thought we wanted to be.

When I listened to the Maron interview, it sounded so fresh and current—as if it had been recorded yesterday. They talked about Hunter S. Thompson and William Burroughs. And Bourdain was so humble. He told Maron that, “the deep fryer awaits at any moment.” In other words, he realized that fame could be, and often is, short-lived. He kept that mentality throughout his career. Even when he had reached his pinnacle, sharing a meal in Hanoi with Barack Obama as part of his aforementioned CNN show, he shrugged it off and looked at it as just another encounter with a fellow traveler.

Although I followed Anthony Bourdain’s career religiously, I didn’t know how deep his struggle with depression was. I guess I should have realized it, considering his longtime heroin use and other battles, which he was very open about, but I just didn’t know. As someone who suffers from Bipolar disorder, I completely understand the ups and downs of the depressed mind. I just wish he had gotten help.

Apparently, in the weeks leading up to his suicide, Bourdain sought medical advice from a mental health professional, but had not heeded it. Oh, how I wish he had. His own mother didn’t even know how badly he was hurting. She had spoken with him not long before he took his own life and she sensed that nothing was wrong—that he was ok. So often people hide the way they feel from everyone around them, for multiple reasons. Either they don’t want to burden others, or they’ve been feeling that way for so long, they’re just used to it.

Depression is a beast, a cold and cruel demon, and for those who suffer with it deeply enough to contemplate suicide, there is help available. If you or someone you know suffers from depression, please reach out. It’s hard to admit the way you feel, hard to admit that life is tougher for you than for some, but there is a way out.

Depression is a beast, a cold and cruel demon, and for those who suffer with it deeply enough to contemplate suicide, there is help available. If you or someone you know suffers from depression, please reach out. It’s hard to admit the way you feel, hard to admit that life is tougher for you than for some, but there is a way out.

Bourdain’s death—and the deaths of far too many celebrities and everyday Americans alike—will hopefully serve as a wakeup call for those needing help and the people around them who need to look for the signs of severe depression.

Contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. Let’s do everything we can to prevent suicidal ideology from being a secret anymore. We have to make a change.

Excellent points all around, ME. Love, your fan in Memphis.