Jason Jones’ Unlikely Journey From The Ballot Box To The Box Office

January 2006: Jason Jones was relaxing in his Mexico City hotel room following a long day of meetings for a political project he was working on. As he prepared to enjoy some tortilla soup while watching a comedic film, Jones received an unexpected call from Marie Smith, wife of New Jersey Congressman Chris Smith, both whom were there for the same meetings.

January 2006: Jason Jones was relaxing in his Mexico City hotel room following a long day of meetings for a political project he was working on. As he prepared to enjoy some tortilla soup while watching a comedic film, Jones received an unexpected call from Marie Smith, wife of New Jersey Congressman Chris Smith, both whom were there for the same meetings.

“Jason, you need to come downstairs and meet Eduardo Verástegui. He’s a telenovela star.”

“What’s a telenovela?” Jones asked.

“It’s a Mexican soap opera.”

“Why do you want me to meet a Mexican soap star?” Jones pressed. “I wouldn’t want to meet an American soap actor!”

“He’s a devout Catholic,” Smith responded. “He’s very pro life.”

“I’m coming down.”

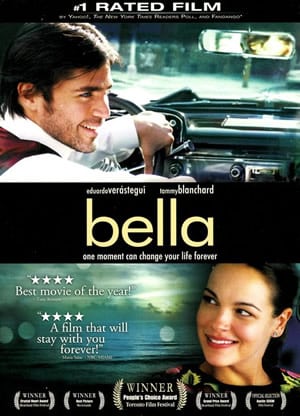

Jones was instantly intrigued. Verástegui had co-produced and starred in a movie called Bella, which was seeking funding for marketing and distribution. It’s content lined up with Jones’ core mission: “promoting the dignity of the human person and protecting the vulnerable from violence.”

Jones then attended a screening of the film. He was hooked.

“After the presentation, I walked up to him and said, ‘I’m here for you—anyway I can help.’” Jones recalls.

Two weeks later, he met with the Metanoia Films team at Notre Dame where they asked if he could help find investors to fund the promotion and advertising (P&A). To that point, Jones had only worked in the political and non-profit works. He had become known for doing favors for anyone who asked.

“If you needed it, I would do it,” Jones says. “So I had all these chips and I tried to cash them in. It didn’t take long. It took three weeks and I raised the P&A for Bella. It was millions. It was beginner’s luck. I’ve never raised money that fast for anything else since.”

As Bella neared its release in October of 2007, Jones returned to his political roots and served as national outreach director for Sam Brownback’s 2008 presidential run. When Brownback dropped out of the primary, he was asked to rejoin the marketing efforts for Bella. Jones had never promoted a movie before so he treated it like a political campaign.

“We divided the market into a series of coalitions,” Jones explains. “For Bella it was pro-life, Catholic, adoption, Latino, and Evangelical. We had five tribes or affinity groups. We had some big dogs on each steering committee. Then I broke it down from there. We had market captains, theater captains and show time captains. Just like an election, we figured out how many votes or ticket sales we needed to win and we’d go find them.”

Jones’ strategy worked to perfection. Before the film hit theaters, they already had $1.2 million in committed ticket sales. Bella ultimately posted a healthy $8 million result at the box office and continues to have cultural impact more than a decade later.

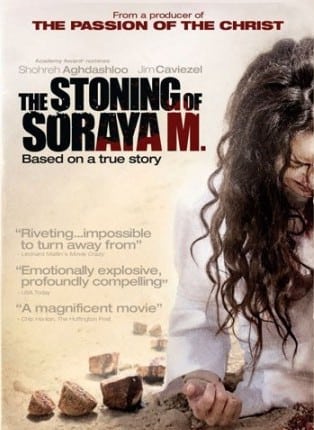

Still, it wasn’t a given that Jones would make the leap into full-time filmmaking. In fact, it took some tugging from movie mogul Stephen McEveety to help him finally make the leap. McEveety (The Passion of the Christ) had served as an executive producer on Bella and asked Jones to help with the 2009 film The Stoning of Soraya M., which starred Shohreh Aghdashloo (24, The Expanse) and Jim Caviezel (The Passion of the Christ) and told the harrowing story of a young Iranian woman’s brutally fatal punishment.

Still, it wasn’t a given that Jones would make the leap into full-time filmmaking. In fact, it took some tugging from movie mogul Stephen McEveety to help him finally make the leap. McEveety (The Passion of the Christ) had served as an executive producer on Bella and asked Jones to help with the 2009 film The Stoning of Soraya M., which starred Shohreh Aghdashloo (24, The Expanse) and Jim Caviezel (The Passion of the Christ) and told the harrowing story of a young Iranian woman’s brutally fatal punishment.

“My mission is to promote the dignity of the human person,” Jones says. “That movie did so in a very beautiful and unique way. The violence in this film makes the viewer repulsed by violence. We put together a very diverse coalition. It was very unique. They all had reason to share that hard film.”

Jones continued to get employment offers from political organizations and film companies. It was easy to say no to those that strayed from his mission. But he loved activism and movies and was beginning to understand how both could work together in a powerful way. Jones already had a non-profit group called H.E.R.O. (Human Rights Education and Relief Organization). He then married the two concepts with the creation of Movie To Movement, a division of H.E.R.O. that finances, produces, and/or promote films and other media projects.

“We only do movies that are in line with the mission of my non-profit,” Jason explains. “That’s how Movie to Movement was born. It was making sure I didn’t drift from my mission. That turned out to be a great success because it’s allowed us to fund all sorts of initiatives for H.E.R.O. Eighty percent of our income comes through Movie To Movement’s work on films.”

Jones has since been involved with numerous short films, feature films, and documentaries including Eyes To See (2010), Crescendo (2011), Sing A Little Louder (2015), and Voiceless (2015), and has multiple projects in various stages of development and production. Even though every movie is a struggle, Jones says that the ability to tell stories on the big screen gives him a fighting chance.

“There’s a disruptive beauty to film,” he explains. “The Stoning of Soraya M was bootlegged by people and tens of thousands of copies found its way into Iran. Just a couple weeks later, the Green Revolution took place. Did our film play a role in undermining the regime? I don’t know. But I do know it had a big part in undermining the image of the regime around the world, so much so that they were obsessed with the film and who we were. So there’s a disruptive beauty to film and I never feel helpless as a filmmaker and as a writer. Film gives me the sense that I can fight back.”

At his core, that’s something Jones has always been—a fighter. He joined the military straight out of high school and, these days, enjoys sparring in the boxing ring or mixing it up with his mixed martial arts buddies in Hawai’i where he and his rather large family reside. In all areas of his life—family, faith, film or fighting (recreationally, that is)—Jones has learned that if you want to do something of lasting value, it’s going to be difficult and it’s going to take time.

“There are no shortcuts in life,” he adds. “If you want to reach millions of people, it’s not going to be easy. If you want to get millions of people to shut off their phones and stare at your story for 90 minutes, there’s no easy way to get there. You’re going to need fortitude.”

To solidify his sobering point, Jones notes that 60 percent of movies are made by first time and last time producers, and take 13 years to get made—seven years once the script has been written.

“Don’t think it’s going to be what pays your bills,” Jones says. “Don’t think you’re going to get rich and famous. If you want to be rich, find a way to make light bulbs cheaper. Find a way to distribute milk from the cow to the table cheaper and quicker. If you want to get into the storytelling business, tell stories and keep telling them.”