In the climatic scene of the R-rated “Gran Torino” (2008), Walt Kowalski (played by Clint Eastwood) puts his hand in his inside coat pocket only to be riddled with bullets from the gang members occupying every window in the house before him. The gang fires because they believe that Walt’s pulling a gun — as he knows they will — when he’s only reaching for his cigarette lighter.

Walt Kowalski gives up his life to protect his next-door Vietnamese neighbors who are targeted by the violent gang. His death solves the problem, as the gang members are led away to jail, presumably for life.

I doubt many people think of “Gran Torino” as a “faith-based film,” despite its being about the redemption of a hellish situation through one man’s sacrificial atonement — the last image of Walt has him lying in a cruciform posture, a worthy imitator of Christ.

Similarly, in “Hacksaw Ridge” when the army company of Medic Desmond T. Doss (Andrew Garfield) waits to go back into battle on Okinawa because Doss hasn’t “finished his prayers,” we realize that we have encountered another follower of Jesus, whose authenticity matches his Medal of Honor gallantry.

Film depictions of faith have now gone beyond mocking stereotypes like Robert DeNiro’s sociopathic Max Cady in “Cape Fear,” or Will Ferrell’s treacly and not-funny prayers to the “little, baby Jesus” in “Talladega Nights.”

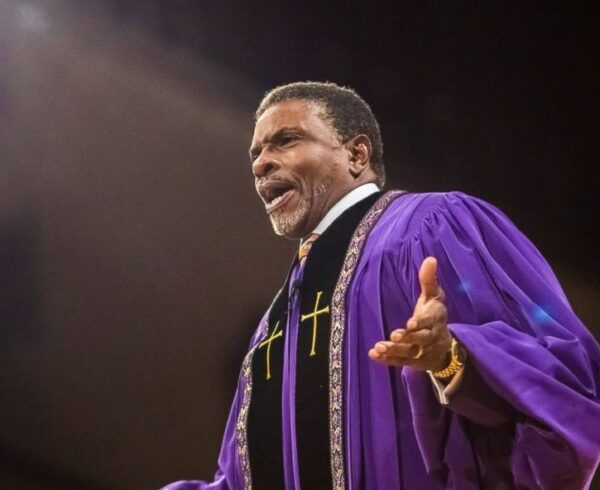

Instead, there are utterly compelling films like “Of Gods and Men,” “Silence,” “Risen” and “Ben-Hur.” Or TV shows like “Greenleaf” (starring the wonderful Keith David) and one of the smartest, most telling sitcoms in years, “The Jim Gaffigan Show.”

Industry executives seem to be recognizing that “faith” and the questions faith addresses are simply part of life. Much of the credit for this recognition goes to Christians who have moved into positions of power within the entertainment industry.

For example, the faith of screenwriter Scott Teems broadly influences the AMC miniseries “Rectify,” and the commitments of Mel Gibson and Jim Gaffigan are well known. Other Christian business beachheads include Mark Burnett, Jr., and Roma Downey’s Light Workers Media as part of MJM, Sony Faith, Walden Media and Giving Films. Pure Flix, a production company and streaming service, is moving into distribution. The Dove Channel is developing original programming. These productions and the growing business infrastructure supporting them constitute the good news.

Still, with the possible exception of “Risen,” the titles I’ve so far mentioned are not what people generally mean by “faith-based films.” What I’d like to suggest is that “faith-based films” follow the lead of a “Gran Torino” and eschew the self-imposed predictability thatseems to stifle success.

By predictability, I am referring to two conventions: 1) someone, somewhere in the film always presents the “plan of salvation,” as evangelicals understand it, and 2) they stay in a PG box.

I share the weariness of F-bombs and gratuitous nudity, but what you can’t do is present gang bangers talking like missionaries.

What stories can do is inspire longing and imitation. How many children have zoomed around their living rooms after watching “Superman”? “Hacksaw Ridge” makes me want to be a person who can draw a deep courage from my faith; it also wants me to possess a faith so palpable that others, who don’t believe in anything at all, can at least respect it.

So even as faith-based films are coming of age, I think some audiences will still say they are “not for me.” I’d therefore like Christians in entertainment to consider the idea that this may not be a prejudiced judgment but simply an accurate one. That might lead us to concentrate our energies in the broader and more helpful directions of “Gran Torino” and “Hacksaw Ridge.”

This article originally appeared at The Washington Times.