“Myth and legend has been an important part of culture since the beginning. Literature began with these stories.” According to one website, a good definition is, “Fantasy is often characterized by a departure from the accepted rules by which individuals perceive the world around them; it represents that which is impossible (unexplained) and outside the parameters of our known, reality. Make-believe is what this genre is all about.”

But what’s sets one author apart from another. How do these minds dream up these fantastical stories. It’s more than just fiction. It’s magic, legend, myth. We grew up with The Odyssey and King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, but how do modern authors apply fantasy and legend to the modern genre?

Our own Grandfather Rock (Chris MacIntosh) posed a number of questions to gifted fantasy author Matthew Dickerson regarding his 3-volume fantasy series The Daegmon War.

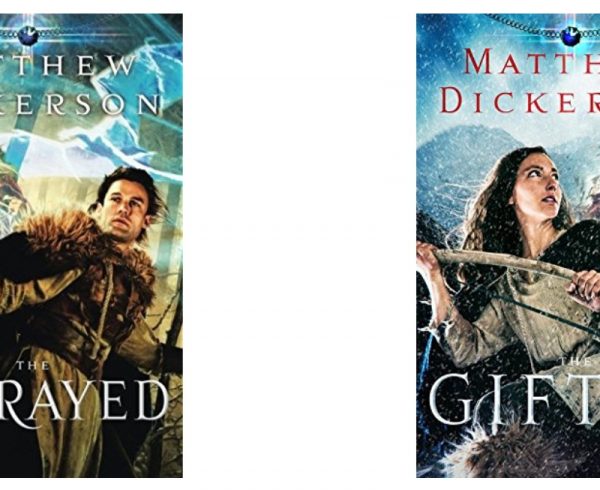

Q: You have just released the third volume of your current trilogy going under the umbrella title: The Daegmon War. Book Three titled Illengond was preceded by The Gifted (Book One) and The Betrayed (Book Two). The trilogy can best be described as high fantasy at its best. My first question is very simply this: in today’s culture is the reading and writing of fantasy just escapism or is there something deeper and more substantial going on here.

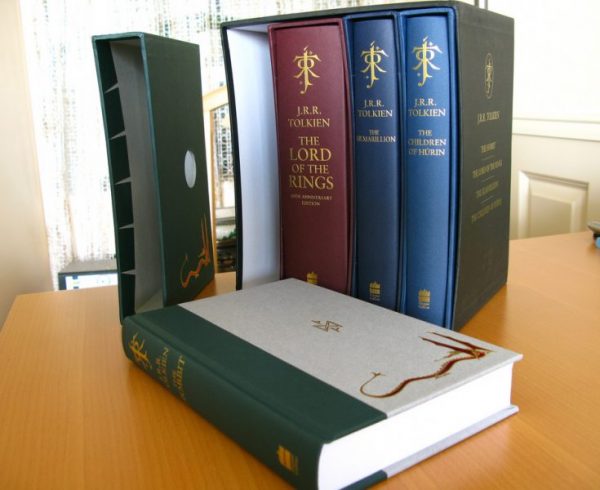

A: Good question. In fact, it’s one that J.R.R.Tolkien addressed several decades ago in his essay “On Fairy Stories” exploring the value of fantasy. For one being held captive, escape is a good thing. Prisoners of war held captive in enemy territory who manage to escape and return home are considered heroes. So with that in mind, I would say that a contrast between “escapism” or “deeper truth” sets up a sort of false dichotomy. Good fantasy literature is substantial and deep, and precisely for that reason it is an escape from that which is insubstantial and shallow.

I think of how Tolkien, in his works of fantasy literature, explored and portrayed the immorality of torturing prisoners, even for the sake of gaining knowledge that might win an important war. It would be better to lose the war, Tolkien’s narrative suggests, than to win the war by becoming the sort of people who torture prisoners. My thinking and understanding about that topic was far more influenced by profound and imaginative narratives set in Middle-earth than by abstract statements or political posturing made in newspaper articles.

Maybe that all sounds too academic or esoteric. When I’m writing a work of fantasy literature—or any other work of fiction or creative writing—I’m not trying to figure out how to insert philosophical ideas into the story. I’m working to tell a really good story with compelling characters who will draw a reader in. I suppose one other aspect is this: in order to create a compelling story that readers will not want to put down, in “epic fantasy”—or what some call “high fantasy”—the stakes are set high; all of the action is around something of cosmic significance. It may be purely for narrative reasons that in epic fantasy whole kingdoms or even worlds are at stake, but whatever the reason, the fact that this is true means the narratives can’t help but explores issues and actions of significance. Some use the term “heroic fantasy” for this type of literature I am drawn to writing and reading. Again the question of what makes somebody or some action “heroic” gets at the deepest questions of human existence.

Q: I have read a number of times that in The Lord of the Rings, Professor Tolkien considered Sam and not Frodo to be the his favorite character in the story even though the tale seemingly revolved around Frodo. In The Daegmon War, there were a number of, for lack of a better term, primary characters. Did you have a favorite and why? [spoiler alert].

A: I’m not sure that Sam was Tolkien’s favorite character. He was certainly the most quintessential common working-class Englishman character, but Tolkien was also critical of Sam in some ways. In one personal letter, Tolkien describes what for him was the saddest moment of the stories: it is when Sam, in his pride and lack of understanding—his “cocksureness” and inability to fathom what Frodo was doing—continues to speak unkindly to Smeagol at a moment when Smeagol was on the verge of real repentance. As a result, the moment is lost and Smeagol never repents and returns to being Gollum. Tolkien blamed Sam for that. Which isn’t to say that he didn’t also like Sam for various reasons.

All of which makes me think of the “heroes” of my story. They all have their faults or failures, yet I came to like or at least appreciate all the members of the main company that my story follows. If I had to pick favorites it might be Tienna and Jhaban, but that’s probably because I’m jealous of their athletic grace and agility. They are both maybe a little too proud, but still people full of integrity and compassion, committed to doing what is right even at great personal cost.

In one scene in The Return of the King, Denethor castigates his son Faramir for his gentleness, telling him that his gentleness may be repaid with death. Faramir replies, simply, “So be it.” For Faramir it would be better to lose the war and die than to win the war by sacrificing virtue. I think Tienna would respond in the same way.

Thimeon was the easiest character for me to write about; I felt like I understood him the best. I’d like to write more about Noab in another book; I think his gift of being able to taste truth (or falsehood) is very compelling. I mentioned that some of the hard work of revision in Illengond, the third book of the series, was rewriting some chapters from viewpoints of other characters. I’m really glad I took on that challenge, especially with Braga who also become a favorite character. I definitely know him better than I would have without that extra work, though I still don’t know him as well as I know Thimeon, Tienna, or Elynna.

Q: What is it that draws you to fantasy writing as opposed to, let’s say, crime stories or romance novels?

A: I guess my answer has two parts. I continue to read literature from a broad varieties of genres and authors, but it’s certainly true that some works of fantasy have been particularly influential and inspiring to me. I also believe that Tom Shippy is correct when he describes it at the dominant literary form of the past century. So I’ve been drawn to try my hand at this form of literature that has been personally very meaningful as well as culturally important.

I also think of what Walter Wangerin Jr. once wrote about Myth, and which I think is more generally true of the broader category of fantasy: “In order to comprehend the experience one is living in, he must, by imagination and by intellect, be lifted out of it. He must be given to see it whole; but since he can never wholly gaze upon his own life while he lives it, he gazes upon the life that, in symbol, comprehends his own. Art presents such lives, such symbols. Myth especially—persisting as a mother of truth through countless generations and for many disparate cultures, coming therefore with the approval not of a single people but of people—myth presents, myth is, such a symbol, shorn and unadorned, refined and true.” In short, I think fantasy literature more than any form of literature allows for something that is timeless and transcendent and deeply meaningful.

Or maybe, more simply, I’d say that the stories I’m drawn to tell just seem to express themselves in the mode of fantasy literature.

Having said all that, I’ve also written historical fiction and narrative non-fiction and I like those forms of creative writing as well.

Q: Were you aware when you set down to tell the tale of The Daegmon War that it would take three books to accomplish the project or did the story expand along the way? How did that influence character development?

A: I really didn’t know how long it would take to tell the story. Equally importantly, I didn’t know how many pages of writing it would take me to get to know the characters and the landscapes and cultures I wanted to explore. At some point early on I realized it would be longer than one volume and I began to imagine two. It wasn’t really until I was finishing the story that I realized that it needed to be a three-volume work, not only because of the overall length, but also because of where the natural breaks were in the story—especially the obvious point that comes at the end of The Gifted (Volume 1). So to answer your second question, I would say that I did not decide to wrote three volumes and then as a result develop the characters further. Rather, the work of developing the characters and the story are what necessitated the 3-volume length.

Q: Obviously the telling of such an epic tale is going to be a long process. Can you walk us through the story of creating such a work from the original germination of the idea until you have the hard copy in your hands.

A: A few years before I started writing The Daegmon War, I wrote a medieval historical novel. The first publisher I sent it to turned it down. The editor told me she loved my character development, and dialogue, and descriptions, but she felt like the novel started too slowly and took too long to get to the main conflict. She suggested I write a fantasy novel that brought readers into the “action” right away.

I responded in two ways. I edited the historical novel and restructured it, focused more on the action, and brought readers more quickly to the tensions and challenges. The revised version was definitely better, and eventually got published by Wings Press with the title The Rood and the Torc: the Song of Kristinge, Son of Finn.

I also took the editor’s suggestion and began a fantasy novel. I stepped right into that opening scene, and wrote what would become the first three chapters of The Gifted. I had little idea where any of it would take me. I didn’t know who the characters were, or the dynamics between them, or their backstories, or the history behind the conflict in which they found themselves. I just let the scene take me where it seemed to want to go. Writing, especially creative writing, is a process of exploration.

So to answer your question, the first stage of that long process of writing an epic tale was the exciting part: following the story and the characters where they lead me, letting the tale unfold, getting to know the various people who had suddenly appeared in the opening scene, as well as the new characters I would meet along the way. As I learned more about the world, I took lots of notes, drew maps, and began to imagine the history and geography of that realm. Since Gondisle is an imagined world that bears some resemblance to our world but also some differences, I also had to think through consistently the laws of that world—not the political laws, but the deeper metaphysical laws of where the fantastic or enchanted elements came from. Some of that work I had to do before continuing that story much further, so that my world would be consistent. Some I discovered along the way.

Then, at some point, the “story” is done. I’ve reached the conclusion. I realized I had a three-volume novel with a complete narrative arc. (Not that any story is ever complete. The characters lives continue on, or not. I’ve begun some new stories about that realm that may someday be published in a new novel. But that’s for another day.) Then came the more difficult work of going back and revising the work, cutting out scenes where needed, in rarer cases adding some pieces, and polishing the prose. In doing this, I ended up with a major revision on the third book, Illengond, changing not only the title but rewriting several chapters using the perspectives of different characters. That was difficult work, as I had to not only re-envision what would be known about a scene from a different limited perspective, but I also had to enter the thoughts of some characters I didn’t now as well. I really liked the result, though. I think it helps the reader get to know more characters, and also makes it more interesting and gives the feel of a faster pace.

Q: Now that the trilogy is complete and you have hard copies available what comes next? Do you go out on the road to promote it via book signings or lectures and how does that coincide with your teaching responsibilities.

A: Well I do get invited to do speak from time to time, usually on a topic related to literature, and so I do some travel. Sometimes with these invitations I even get to talk about my creative writing or to do a reading of my work, and now and then there is a bookstore involved. It’s always fun when there is a book table with my books and I can sign copies or answer questions about my writing. But the reality in today’s publishing world is that it’s very hard for publishers to fund any sort of speaking tours, so the only time I really travel is when I’m invited someplace to speak. So between lack of publisher funding and my day job as a college professor which makes it hard to be out of town on most weekdays, I don’t do a lot of promotional travel. I’m dependent mostly on word of mouth for people to hear about my books. If somebody reads one of my fantasy novels (hopefully likes it), and posts a photo and short blurb to Facebook, Instagram, or Goodreads—or maybe puts a review on Amazon—that’s the best way for people to hear about The Gifted, The Betrayed, and Illengond.

Q: So what can we expect next from the writings of Matthew Dickerson?

A: My next book due out is a collection of creative narrative non-fiction essays—a mix of outdoor writing and nature writing and personal essays–about places wild and almost-wild. Most of the essays are set in national parks and national forests, like Lake Clark National Park and Glacier National Park where I spent a lot of time this year. I also have a couple books due out about trout, rivers, and fly-fishing. But I hope soon to get back to working on a new fantasy novel set in Gondisle a few months after the end of Illengond. I began it some time ago and I really like the characters and the direction it is going. I just need to go back to it.

Editor’s Notes: All three volumes are available on Amazon among other outlets and just I need time for Christmas.

You can follow Matthew on Facebook. You can also follow Grandfather Rock on Facebook.