Gone are our real life heroes. It’s time for some make-believe ones. Storytelling cultural creatives must come to the rescue.

We are living through a necessary national catharsis of sexual misbehavior. I presume that the reality is far worse than is being reported. But the nightly news is no longer “family friendly.” The litany of perversions across a host of industries leaves one disgusted. Social trust is in the toilet. Heroes and integrity appear to be in short supply. Culturally we will suffer scandal PTSD.

Hollywood directors and television showrunners have a special responsibility in times like this. Social scientists and storytelling cultural creatives both know the power of story. Stories are what help us make sense of the senseless facts that bombard us day in and day out.

Some have claimed that we live in a “post-fact” era. Decorated reporter Carl Bernstein corrected this assessment on Bill Maher. We don’t have a crisis of facts, he explained, we have a crisis of context. We no longer know how to connect the dots. We have a frame problem not a fact problem. Facts abound, it is meaning that is in short supply.

Stories are how we make sense of facts. We are told that everyone should write a memoir, because it helps us put our lives in some order and gives them some meaning. When we are not a part of something larger than ourselves, we have to make sense of it from the inside out. In the absence of reality, a memoir may fill the gap.

With the power of stories and storytelling affirmed, what social responsibility do showrunners have to the common good?

One frequently watches shows where the protagonist is morally bankrupt. Antiheroes are in vogue. Machiavellian power, greed, and debauchery dominate contemporary protagonists. One cannot watch House of Cards, Scandal, How to Get Away with Murder, Teachers, and Game of Thrones without feeling like one needs to take a moral shower. Politicians, cops, doctors, teachers, coaches, sports figures, and businessmen are all depicted as corrupt, greedy, lustful, and murderous. I often ask myself at the conclusion of the episode, “How is this story helpful to our society?” How does this story call us to our better angels?

Harvard M.D. and Hollywood showrunner Neal Baer has been connecting storytelling to social policy for the past decades. “I stand in three worlds: storytelling, which is TV, movies, and novels; medicine; and social entrepreneurship,” he says. “A lot of people get their health information from TV and the Internet and act on it, so I didn’t want it to be inaccurate. I don’t think about it as educating, because I don’t want to be pedantic. I think of it as trying to tell very rich, accurate stories that try to pose complex, ethical issues.” His moral compass is about using storytelling to make the world a better place.

Of late television has even gotten worse as the era of the anti-hero has moved from dramatic TV to the nightly news. Financial corruption and sexual scandal pervade the airwaves. One news commentator suggested a solution to the political posturing between the two parties is that perpetrators of sexual harassment simply join a new third party, the Perv Party. It is a bull market for the Perv Party. Indecency has become so common as to numb our senses. Lost is a sense of trust, respect, and integrity. Male piggish behavior has reached epidemic proportions. One feels the need to apologize for one’s gender.

After we choke back our politically correct self-righteousness, cynicism takes over. American democracy is dying of a thousand cuts. And yet, we continue to long for examples of goodness, fairness, and basic decency. We long for them and need them. We hope against hope that societal churlishness does not go all the way down.

In this debauched cultural context two programs stand out: Blue Blood and Designated Survivor. Blue Blood explores the ambiguities of justice in a fictional New York City police department. There is a lot that is wrong with American justice and policing. The cynical may feel that shows such as Blue Blood whitewash the crimes and provide cover for the guilty. But moral complexity is a regular feature of this show. That its characters affirm faith, family, and integrity is its strength and cultural gift.

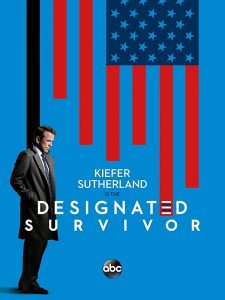

In a similar manner, political integrity is demonstrated in Designated Survivor. President Tom Kirkman (played by Kiefer Sutherland) is an everyman thrust unexpected into the highest office of the land. As a progressive-leaning moderate independent, he works hard to demonstrate a political agenda that crosses party lines. This show is the antidote to House of Cards and Scandal. And while this show has problems with dialogue with many acknowledge critics of writer David Guggenheim, it consistently discusses and provides a useful take on some of the most vexing political dilemmas of our time.

The show about how to deal with Civil War monuments is a good case in point. The episode has a recognized Black Civil Rights hero advocating for keeping the statues in place as a way of reminding the country of its racist past. Remembering is not always celebrating.

Designated Survivor lacks the snarkiness and smarts of Aaron Sorkin’s West Wing or The Newsroom. But then again, Sorkin is a one-of-a-kind writer. But Designated Survivor does put forward a complex presidential character who consistently stands for integrity and nonpartisanship in an Oval Office where these attributes are often in short supply. For the most part, the show is able to do this without preachiness, which is an accomplishment in a day when the ideological tweet replaces substantive dialogue.

We need fictional stories that call us to our better angels. The nightly news easily does the rest.