Waking Up

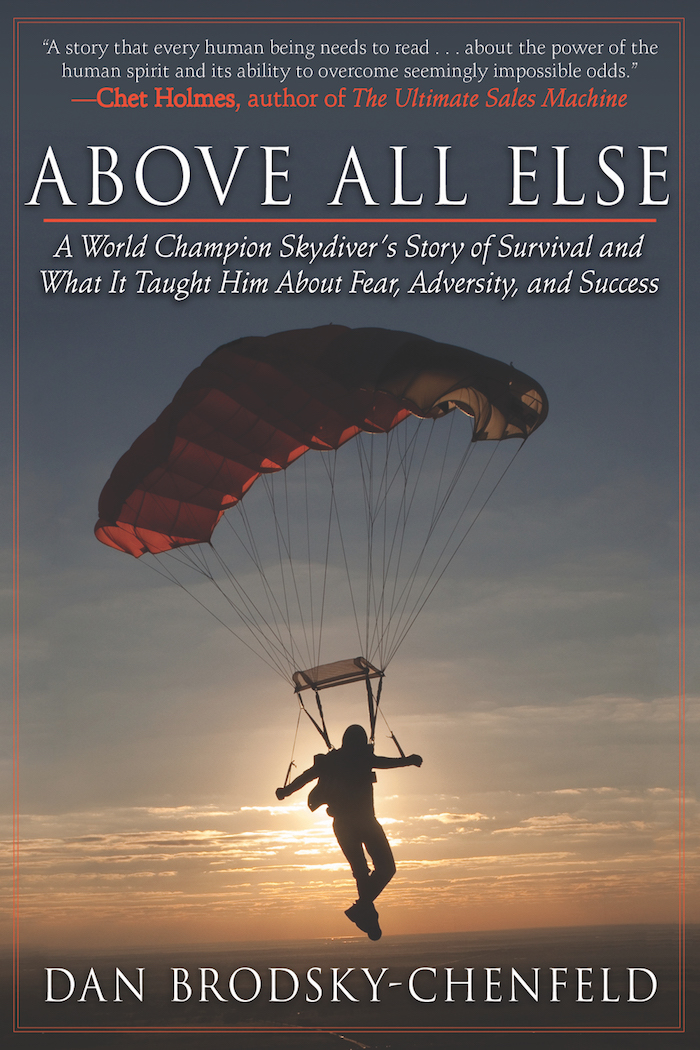

The following article is taken from the new book, Above All Else.

Something was wrong. I was groggy, fading in and out. My body felt tired, weighted down. What was going on? I tried to see but my eyelids were too heavy to lift. I summoned all the strength I could but still didn’t have the power to peel them open. The last thing I could recall was training with my new skydiving team, Airmoves. After nine years of competition, much of which was spent living in my van and eating out of a cooler so that I could afford team training, the owners of the Perris Valley Skydiving Center in California had presented me with a team sponsorship opportunity. I would get to pick and run the team. They would cover the training costs.

This was it, the opportunity I had always hoped for. Since money wasn’t an issue, I was able to pick the teammates I most wanted. The first person I called was James Layne. I had known James since he was eleven and had taught him to jump when he was only fourteen. His whole family had worked at my drop zone in Ohio.

James was like a little brother to me. Even before his very first jump seven years earlier, we had decided that someday we were going to win the national and world championships together. This was our chance, a dream come true…

…

We were five months into our training and had made about 350 practice jumps. Everything was going better than I had ever imagined, and I have quite an imagination. We were improving at an unheard-of pace and had already gone head-to-head with some of the top teams in the country. The U.S. Nationals gold medal was in our sights.

And then . . .

The crust on my eyelashes glued them shut. Using the muscles in my forehead, I finally pried them open a crack. A faint white light was all I could see, like I was inside of a cloud. It was silent. Where was I waking up? Was I waking up? Was I dead?

…

I knew I wasn’t dead. I squinted, trying to see more clearly. The white light slowly brightened. A few small red and green lights came into view. As if coming from a distance, faint electrical beeping sounds began to reverberate from the silence.

My vision started to sharpen. I could see I was surrounded with lights, gauges, hoses, and wires running in every direction. The glowing white light wasn’t the heavens. It was the bedsheets and ceiling paint of an ICU hospital room.

I stared straight up from flat on my back, the position I found myself in. What’s the situation? I thought that James and I must have been in some kind of accident together. James was gone and I wasn’t.

I tried to pick my head up to look around the room. My head wouldn’t move. I tried to turn my head to look to the side; it wouldn’t move. Oh my God, I thought. I can’t move my head. I’m paralyzed. It can’t be true. Don’t let it be true. This can’t be the situation.

I was filled with a sense of fear far greater than anything I had ever experienced before. I felt myself starting to give up and caught myself. Don’t panic, don’t panic. I closed my eyes, took a breath, and tried to calm down. It’s got to be something else, there has to be more. I told myself not to come to any conclusions too soon, to pause and reevaluate the situation. I started again.

I opened my eyes. I could see a little more clearly now, and there was no doubt I was definitely in a hospital bed complete with all the bells, whistles, buzzers, and instruments. I tried to move my head again. It wouldn’t budge. “Stay cool, stay cool. Try something else,” I told myself.

…

I tried to wiggle my fingers. It felt like they moved. I tried to move my hands. I could swear they worked. Did they move? I couldn’t turn my head to see my hands but nearly stretched my eyes out of their sockets trying to look down to verify that my hands were actually moving.

Peering past the horizon of the bedsheet, there were no hands in sight. I tried to lift my hands higher. They felt so heavy. Were they moving, or was it my imagination wishing them to move? Slowly, I saw the bedsheet rise. Like the sun rising in the morning, slow but certain. I brought my hands all the way up right in front of my face, trying to prove to myself that it wasn’t a hallucination. I stretched out my fingers, clenched my fists, and then stretched them out again. I put my hands together to see if my right hand could feel my left and my left hand feel my right. They worked. Yes! What an incredible relief. My arms and hands weren’t paralyzed. Okay, so far so good, back to my legs.

I tried again to move my toes and lift my feet. They were too far away to see and too heavy to lift. I gathered all the strength I had, as if I was trying to bench-press four hundred pounds, and focused it on my knees. Ever so slowly, the bedsheet started to lift. Slowly my knees came up high enough that I could see they were moving. I wasn’t paralyzed, not at all.

I still didn’t know what the situation was, but no matter what, it wasn’t as bad as I had feared. I felt a sudden relief, and though I had never been a person who prayed very often, without even thinking I found myself thanking God for lessening my burden.

Why couldn’t I move my head, though? I reached up with both my newly working hands to feel my head. As I did, I came in contact with two metal rods. As I explored further I realized my head was in a cage. I couldn’t move my head not because I wasn’t capable but because it was being held still by a halo brace.

My neck must be broken. But for a person who moments earlier thought he was completely paralyzed, a broken neck seemed like the common cold. The experience of thinking I was paralyzed from head to toe was truly a gift. It would forever put things in perspective for me. I decided at that moment that I would never complain about my injuries, no matter what they were.

…

The doctor was concerned about the nerve and brain damage but seemed confident that I would ultimately be able to walk out of the hospital and lead a relatively normal life, as long as my normal life didn’t include any contact sports or rigorous activity at all. I would certainly never skydive again.

A little while later, Kristi, my girlfriend, came in. I asked her what had happened, but she dodged the question. I kept asking her, pushing her; I had to know. Finally she said, “It’s bad, Dan, it’s so bad.”

That was the first time it occurred to me that if James and I were in an accident of some kind, it was likely that the other members of Airmoves were in the same accident. I asked her again what had happened. “It’s so bad” was all she could say. I pushed her relentlessly. Finally, she told me. There was a plane crash. A plane crash? I hadn’t even considered a plane crash. I realized what that could mean and tried to prepare for the worst, that my entire team may be gone. The sudden emotional barrage that hit me was overwhelming. I was starting to lose control and caught myself. I closed my eyes, took a breath, and calmed myself down.

I later learned that Kristi had been by my side since the crash. She and my friends and family did not know how, if and when I woke up, they would tell me that James was gone.

I asked her, “How’s my team?” She tried to speak, but still, the only words she could muster were, “It’s bad, Dan, it’s so bad.”

I needed an answer. I said, “I know James is gone. How is the rest of the team?” She froze in disbelief. She looked at me, staring deeply into my eyes, and asked, “How do you know that?”

I answered directly, “He told me.”

…

The emotional bombardment continued as Kristi told me who we lost. The names included members of Tomscat, a team from Holland that I was coaching, the pilots, instructors, and camera flyers who worked at the skydiving school, and students who were there for their first jump, in what was supposed to have been an experience of a lifetime for them. Kristi was right: It was bad. So, so bad.

Because I was just learning about this, I had assumed that it had all just happened. As I was absorbing this information, I was hit with another shocker. The crash had occurred over a month ago. I had been in a coma for nearly six weeks.

Published by Special Arrangement with Skyhorse Publishing. Above All Else by Dan Brodsky-Chenfeld is available for purchase at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or your local indie bookstore.