The modern world is a place of paradox. Including the perplexing phenomenon that we have never spoken more loudly or more often of choice, from “consumer choice” to “reproductive choice”. Yet never, in the West, have we more sharply restricted choice.

We are hedged in with laws, regulations and taboos that would have appalled our medieval or Victorian ancestors. As Tocqueville feared, the modern despotism does not crush or strangle but enervates, binding as the Lilliputians bound Gulliver with endless tiny strings. Somehow the right to choose has expanded so cosmically that it swallowed its own tail… and the right of others to choose.

I’m not thinking only of sexual matters. But given the modern obsession with sex the paradox is highly visible here. The mantra of “a woman’s choice” and of “dignity in dying” means that we shall decide on our own terms even when to tolerate life and when not to. Yet we increasingly restrict free speech about abortion and the right of doctors not to be complicit in euthanasia.

The resulting restriction in choice is drastic. In forbidding doctors to follow their conscience we also deny patients the right to choose a doctor they know will not shuffle them swiftly out of their mortal coil behind a thin veil of implicit consent or incapacity to decide. Just as if we allow men to choose to enter a women’s bathroom, we deny all women the choice to perform intimate bodily functions in a gender safe zone.

Restricting choice in the name of choice

This paradox is far too widespread to be explained by quirks in one country’s culture or political institutions. From Canada to Tasmania you find anti-free-speech “bubble zones” around abortion clinics. And recently in France, ads showing happy Down syndrome children were banned lest they trouble the conscience of women who had abortions. Again, the British Medical Association recently urged health care practitioners not to call pregnant women “expectant mothers” to spare the feelings of the transgendered. So every woman thrilled to be an expectant mother, thrilled to join that long and brave chain that has kept the human story going over many thousands of generations, may not have their feelings acknowledged for the sake of those who choose not to be male just because of that dangly thing the BMA associates with “assigned” rather than “biological” gender.

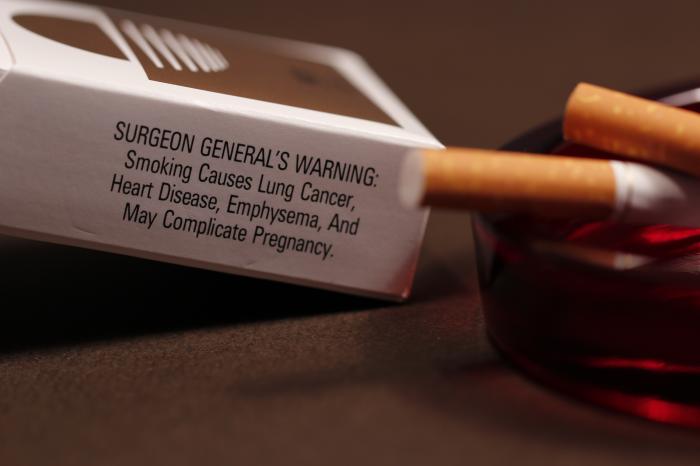

The phenomenon of restricting choice in the name of choice, including stifling a woman’s right to put nicotine into the body over which she wielded unquestioned sovereignty a few minutes back, is also highly visible in the increasing intolerance of anything on campus that makes anyone feel uncomfortable, from controversial speakers to scales in a women’s gym. The argument is that students should be allowed to choose only soothing, confirming words and ideas even if it requires chasing out or punching out guest lecturers.

The extent of the paradox is underlined by the difficulty people have in seeing it. In a brief version of this argument in the National Post in March 2017, I quoted high-society fashion icon, rebel and no longer incongruously Dame Vivienne Westwood, looking back 40 years at the Summer of Punk, at which time she was the girlfriend of Sex Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren, saying that punk “planted an attitude: Don’t Trust Governments. Ever.”

Vivienne Westwood model in a 2014 show with a climate change theme. via Ecouterre

I ran into that quotation in a June 24, 2016 Evening Standard magazine I found in the Tube while filming on Constitutional matters in Britain last summer. It was an issue celebrating the 40th anniversary of the Summer of Punk amid dystopian ads for remarkably expensive cosmetics and clothes to turn women into rather unwell-looking sex objects.

As a libertarian on policy who is conservative on metaphysics, Westwood’s warning sure sounded good to me. But it also sounded weird, because you know without having to ask that the various tattooed and pierced androgynes buying these products, like Westwood herself or the hordes of “rebels” infesting the commanding heights of our economy, culture and politics, are not even Red Tories, let alone genuine conservatives or libertarians.

If you see someone on the subway with a dyed Mohawk or painful-looking body piercings designed to discomfit the long-vanished strait-laced bourgeoisie, in a vest that’s a bargain at 295 quid, you know for a fact the only reason they don’t vote Liberal, Labour or Democrat is that they vote socialist or communist. In short, they vote for parties whose raison d’être is to expand government beyond all bounds, seeing it as the solution to every imaginable problem from concussions to rudeness (except their own).

Hating the government but giving it all power

We can’t make a Zeitgeist out of a single Westwood. But while drafting that National Post column I also ran into a Washington Post article: “Why Hollywood Loves to Hate the Government” subtitled “In movie after movie, Hollywood has urged us to question the motives and methods of government agencies and officials.” Yet Hollywood is as famously liberal as the fashion establishment; most actors who did not support Hillary Clinton in last year’s presidential election backed Bernie Sanders. So how is it that people who utterly distrust government also want to give it all power in the name of the very choice they seek to restrict?

The answer is that in the modern world we have radically redefined choice. No longer do we seek freedom to decide among alternatives. Instead we demand the right to dictate what the alternatives shall be. Instead of freedom to act as we wish provided it did not infringe on the rights of others, and to seek our own salvation in fear and trembling, we desire, nay demand, the right to choose even to take from others and to choose what the moral law shall say.

It looks like the expansion and perfection of choice, as the 1982 Canadian Charter of Rights looked like the expansion and perfection of constitutional rights going back to Magna Carta and beyond. But, like the Charter, it instead deforms, even negates what it claims to perfect.

This temptation confronts libertarians as well as leftists. Too often the former value the act of “choice” as inherently validating; instead of defending freedom because to be a right choice a decision must first be a choice, they believe that, provided it is a choice, it must be self-validatingly right. Which is certainly a widespread conviction in the era of Theodore Dalrymple’s “individualism without individuality”. And if you quote Tom Masson’s “Be Yourself is the worst advice you can give to some people” you are badly out of joint with the times.

An inexorable trend, long foreseen

How did we get here? It is at once logical and insane. As Chesterton predicted,

“The modern world will not distinguish between matters of opinion and matters of principle; and it ends by treating them all as matters of taste.”

But it does so because, as Joseph Conrad in Heart of Darkness and, in his own tormented way, Friedrich Nietzsche foresaw, once we banish absolute truth nothing is left but the imperial will.

Tocqueville also foresaw its political manifestations, in a democratic state that

“covers the surface of society with a network of small complicated rules, minute and uniform, through which the most original minds and the most energetic characters cannot penetrate, to rise above the crowd. The will of man is not shattered, but softened, bent, and guided; men are seldom forced by it to act, but they are constantly restrained from acting.”

Thus freedom of choice is praised on every side by those who strike the cigarette from your lips even outdoors, slap a bicycle helmet on you and force you to raise your deck railing by one inch. But why?

Cardinal Manning once said, “All differences of opinion are at bottom theological.” And while the 19th century went to church, got married and wore starched collars, it was increasingly devoted to a materialistic, reductionist science, immensely successful from the Renaissance on in unravelling mysteries in chemistry, physics and mechanics, that saw humans as bags of chemicals shaped by random chance, activated by deterministic electrical reactions, whose consciousness was a puzzling epiphenomenon and whose souls did not exist.

As James Clerk Maxwell put it in his essay, “On Faraday’s Lines of Force”:

“The aim of exact science is to reduce the problems of nature to the determination of quantities by operations with numbers.”

That was in 1856, when Victoria was not yet 40 and Albert still alive.

This project succeeded all too well, with man brought down to the level of a mere part of nature and then to a jumble of quantities whose behaviour was dictated by operations with numbers without a ghost of free will anywhere in the machine.

The stereotypical radical may be a muddy 1960s hippie or unwashed Occupy activist who has never come in contact with reason. But it is the hyperrational “social sciences” that extended this dreary vision into what was once the “humanities” and left them a barren social justice warrior wasteland full of deconstructionists shouting that words mean nothing, like the Cretan saying all Cretans are liars.

Back to the world before Christ

The curious result of all this rationalism was to take us back to a pre-Christian world in which morality is absent and myths and cultural practices make no sense. I’ve always found it disquieting to read, say, Homer, or Ovid, because despite the authors’ best efforts the religion of the Greeks and Romans doesn’t make sense. It has no moral core or theology. The good are not rewarded nor the bad punished, in this world or the next. Sure, once in a while Zeus rewards someone who exhibits hospitality and arrogance is punished. But ye Gods these gods.

The claim that man has made God in his image, frequently and foolishly levelled at Christians, is, I think, very much true of Olympus. If we were made immortal and nearly omnipotent without being cleansed of sin, we would act exactly like Zeus and his fellows and woe betide any mortal who caught our eye.

Only with the coming of Christianity, and before that within a smaller community Judaism, is there any expectation that the world will make sense, a God who proclaims that Truth will make you free. And it did, with enormously fruitful results including the birth of genuinely scientific inquiry of a sort never before seen even in Aristotle, with his bizarrely anti-empirical claim that men have more teeth than women. Yet as this mighty intellectual edifice rose, it dethroned Christ and enthroned man not as God’s work but as a particularly clever and bloodthirsty ape.

The contribution of the capitalist right

It would be easy to locate the resulting apotheosis of choice on the left, which certainly seems to have embraced it with something very like madness with respect to silencing speech as “hate”, to say nothing of sex, going with blinding speed and strong internal consistency from choosing sex without commitment to choosing abortion to choosing divorce to choosing euthanasia to choosing your own genitals in 30-odd configurations only you can see. But why is resistance to such ideas and practices now so feeble?

Henry Ford Memorial in Dearborn, Michigan by Marshall Fredericks. Photo: Goldnpuppy CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The modern project of liberation is metaphysically very deep, and includes many arch-capitalists as well as socialists. It was Henry Ford, not some union radical, who called history “bunk”. And for every leftist touting “social change” without specifying direction or purpose, there’s an ad for new and improved everything for your modern lifestyle, while Apple and Google and Microsoft want to rock our world every year with life-changing new products.

The complaint by David Brooks of the New York Times about a decade ago about the “the economic individualism of the right and to the moral individualism of the left” underlines that whether we authentically self-create through sex toys or high-tech ones is secondary.

As libertarian giant like Friedrich Hayek wrote in The Road to Serfdom,

“The guiding principle that a policy of freedom for the individual is the only truly progressive policy remains as true today as it was in the 19th century.”

Progress without end, amen. We’ve had 150 years of it and are no closer to our goal. So we must run faster until we drop, exhausted, and others stronger, purer and more Nietzschean leap over our shabby corpses.

It’s the dream of someone like Peter Thiel, humanist, co-founder of PayPal and a libertarian, who burbles that creative technological breakthroughs “rewrite the world” and seeks innovative heroes who transvalue incessantly, creating in isolation in the proverbial garage, overthrowing traditions from without, faster today than they can be created. Or Richard Branson, a capitalist and… and… minister of the Universal Life Church Monastery which has no beliefs, ordains anyone free and says respect other people’s rights.

Or even Conrad Black, who once told a reporter he was feeling philosophical on his way into a Hollinger board meeting and when a reporter asked which philosophy said “Darwinian capitalism, as always.” That was 13 years ago and possibly he feels differently today.

But while libertarian demiurge Ayn Rand’s characters resent state restrictions as limits on their Olympian self-creation, they shun state aid from haughty pride, not reason. Her cold and impoverished metaphysics offer no real reason why they should not manipulate the state for personal gain if they happen to be good at it, just as they do the bodies of others in bed. But why?

Reducing ourselves to absurdity

Because virtually everyone now believes in radical choice. Not between good and evil but what these terms shall mean. If there is no law written on the human heart, except that of survival of the fittest by our relentless genes, they cannot mean anything. As Herbert Spencer at one point confessed with remarkable understatement, as far as ethics were concerned “the Doctrine of Evolution has not furnished guidance to the extent I had hoped.” Nor could it, since by that doctrine our consciousness is not a process of rational choice among objective alternatives but a weird side-effect of a mechanistic process unfolding inexorably since the Big Bang.

Darwin himself insisted that despite his theories man’s moral obligation was, as always, to “do his duty.” And he was buried in Westminster Abbey in the late 19th century — along with the civilization and mental framework in which such a response was coherent. As Darwinian historian of biology William Provine put it, with commendable frankness, in this framework “There is no ultimate foundation for ethics, no ultimate meaning in life, and no free will.”

This whole project isn’t working very well. As Matthew Crawford observed, in a world of unlimited choice with taboos all shattered and the fragments swept away,

We are now very fat, very much in debt, and very prone to divorce.

And say what you like about persons of size, alternative economic and sexual lifestyles, we know something is wrong. And it came at us from everywhere. The market sold us junk food, it and the state encouraged profligate borrowing, and the left dissolved the family. We are all in this together.

And we resemble Slartibartfast, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy’s wise old man with a secret sorrow (his name). He tells Arthur Dent:

“I think that the chances of finding out what’s actually going on are so absurdly remote that the only thing to do is to say, ‘Hang the sense of it,’ and keep yourself busy. I’d much rather be happy than right any day.” Arthur asks “And are you?” And Slartibartfast replies “Ah, no. Well, that’s where it all falls down, of course.”

And indeed it does all fall into an abyss with no bottom, as relativism always does. But we arrived here logically, with Victorian precision, coolness, detachment and rational reduction of everything to meaninglessness, abolishing man and morals and leaving only the imperial ego howling in the wilderness.

Thus we find the success of the materialist reductionist project in reducing man to material, something without rights or ethics, choosing frantically in a doomed quest for meaning without, in fact, having free will with which to choose. And to try somehow to assert his existence against this bleak and overwhelming backdrop he increasingly chooses to impose his will on others.

Exactly as one would expect from an entire civilization that ate the apple, dethroning God as the author of moral law and seeking to write a new one without pen or paper let alone authority, grounded in a metaphysic of an evolutionary war of all against all and creating a similar free-for-all in public affairs.

This review originally appeared at Mercatornet.com, and is reprinted with permission.