My life has been marked by periods of severe adversity, but also by moments of exquisite joy. My childhood, during which I spent time in a Japanese concentration camp, had its nightmarish aspects, but that’s far from all that I remember.

An Untied Shoelace

Mom and Dad were medical missionaries in China. I was raised there with my three brothers and two sisters.

In the summer of 1937 the eight of us went to Shanghai for a family holiday. I was five years old. Dad was taking all of us to the park to play and he noticed that my shoelace was undone. He pointed this out to me and probably thought that I would tie it when we arrived at the park. However, I immediately knelt down to try to tie it.

After struggling for a few minutes I looked up and found that my father and siblings had disappeared. I was in the middle of a busy Shanghai street, completely lost.

Fortunately, an apparently wealthy and strikingly stylish Chinese lady took me by the hand. She wore an elegant, embroidered, silken dress, blue with dragon patterns, and spoke kindly to me in perfect English.

She called a rickshaw runner over to where we were standing and, in Chinese, told the runner to take me to the police station. She gave him the fare and, I now believe, a generous tip for he smiled with a broad grin and bowed slightly.

I was far too scared to thank her but obediently climbed into the rickshaw. I was sitting, small and lonely, in the middle of the wide rickshaw seat, wondering where I was being sent, as I did not know the words for “police station” in Chinese.

The journey was long and bumpy and the rickshaw old and rickety. The seat smelled of grease and tobacco. I watched the back of the runner’s neck, where little beads of sweat were appearing as he hurried along. He must have felt responsible for me. Looking down I noticed that my shoelace was still undone. Not that it mattered any more. I was overwhelmed, and felt helpless.

The police station seemed a long way away but we eventually arrived. The rickshaw runner dutifully handed me over to an English Bobby. I realized that I was now in the British-controlled section of the city. It comforted me that I could hear English spoken again, but the sense of being alone and surrounded by complete strangers came over me like a thick, dark pall. All I could say was “I want my mother.”

The policeman, in a smart blue uniform with bright brass buttons, told me to sit on a little stool in the main reception office. I told him my name and said that my dad was a missionary doctor.

The policeman towered over me on a high stool making notes on his pad. The smell of his cigar wafted down to me. I felt very small. Being lost was a completely new experience. During what seemed an eternity of waiting, I wrestled with this strange sensation. It consisted partly of fear but partly of adventure into an unknown world. I couldn’t put the two emotions together and began to cry.

What would Mowgli do now? I wondered. (Mother had been reading The Jungle Books to us kids.) The waiting seemed without end.

I am still filled with wonder at what happened next. I saw my mother advancing toward me from across the room, but behind that simple fact was an eternity of meaning. Seeing my mother’s face meant I had been found. I will never forget that moment. Looking back, and from my exquisite joy, I saw that being found had everything to do with the love of my family and little to do with location.

Life was wonderful again. I was living a new life, a found life, one of vivid colors and, above all, one in which I was loved. I had survived the abyss and was all the more certain of my mother’s love. If I could be rescued from the streets of Shanghai, then I could be rescued from anywhere. This gave me a new sense of self-confidence. I quickly learned how to tie my shoelaces. This, my first experience of exquisite joy, was ultimately a sensation of being overwhelmingly loved.

Midnight on a Prison Ship, Four Years Later

Japan invaded China in 1937 and the Shanghai that we knew was to be completely changed. In 1940 Mom and Dad left us six at the Mission boarding school on the coast at Chefoo while they traveled across no-man’s-land to Lanchow, thirteen hundred miles inland, to run a mission hospital. We had been completely separated from them, physically and emotionally, when we received the news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

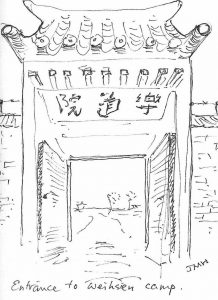

Japanese cavalry and infantry occupied Chefoo and turned our school into a temporary prison. After ten months of extreme congestion, the news came through that we were to be moved to a much larger prison camp at Weihsien, a hundred and fifty miles inland. The journey there involved two stages, a ship to Tsingtao and then rail to Weihsien.

Japanese cavalry and infantry occupied Chefoo and turned our school into a temporary prison. After ten months of extreme congestion, the news came through that we were to be moved to a much larger prison camp at Weihsien, a hundred and fifty miles inland. The journey there involved two stages, a ship to Tsingtao and then rail to Weihsien.

The Japanese did not provide any food for the journey. We were completely out of bread. The baker who had delivered bread to the school agreed to supply it for the crossing and to deliver it directly to the Japanese ship. However our hearts sank as the boat left the dock and the baker had not arrived. Inexplicably, the boat had to drop anchor out in the bay for a few minutes so the enterprising baker secured a rowboat and delivered the bread just in time.

There were 300 of us crowded into the 150-foot steamer. With no cabins and only bare decks, the school staff and children were allotted the hold for sleeping quarters. We lay head to tail like sardines, or shoulder to shoulder, if preferred, on the flat boarding, without an inch to spare. There wasn’t much sleeping; the slightest movement would disturb those on each side of me. It was stiflingly hot. No toilet facilities were provided. The smell of urine permeated the hold. The hatches were battened down at night and no one was allowed on deck.

On the second night I could not stand it any longer and managed to slip out through a carelessly unlocked hatch to the blissful coolness of the deck. It was late, about midnight. I was restless and hungry but my sense of elation at having escaped the “dungeon” overwhelmed all other feelings, even those of conscience. After being so desperate down in the hold, it did not matter at all that I was breaking the rules. All the adults were asleep, I told myself. I declared myself king of the most beautiful midnight dream ship in the world.

Moving quietly to the bow of the ship, all alone, I mounted my throne. I sat with my feet dangling over the edge, legs on either side of the steel cable that stretched from the bow to the top of the foremast. With a full moon above and a moonlit ocean rippling to the horizon, I seemed to be looking out into infinity. This was my moment! Gone was my hunger and restlessness. Gone was my fear, even though I knew we were going through mine-infested waters. Gone was my sense of being an orphan.

Strangely, I felt a sense of complete peace. Everything I had experienced in the last few days of uncertainty, and dread of what might well be a cruel prison camp ahead, argued against this moment. But there it was, inexplicable and intimate. The overwhelming sense of joy that I had experienced after being lost in Shanghai had been made tangible by the immediate presence of my mother. Now, Mom and Dad were hundreds of miles away. Yet, here again was this same immediate sense of being loved. The God my teachers had told me about had always seemed distant. Whatever the source of this love, I could accept it and rest in it. This was real, compellingly real. It took my breath away and I wanted to stay in this magical moment for ever.

C.S. Lewis describes moments in his life of inexplicable wonder, longing, beauty and awe. He calls them moments of being “surprised by Joy.” For him they became signposts toward a spiritual reality he knew nothing about as an atheist professor at Oxford University. Of all the emotions I experienced that night – peace, longing and the exhilaration of release – an overpowering sense of joy trumped them all.

I don’t know how long I stayed on my “throne.” I was getting cold. Tiptoeing back to my cramped space below deck without waking anyone was a challenge but I managed it. I left the hatch I had used for my escape looking as firmly secure as possible and quietly laid down on the hard boarding, then fell asleep immediately. I kept the secret of my temporary escape as close as I could but eventually shared it with my best friends, Jimmy and Theo. Naturally they were jealous, but in an understanding way.

The memory of it had a profound effect on the dark days ahead. It had been only a temporary escape but my spirit had found a lasting way of escaping some of the harshness of the months ahead.

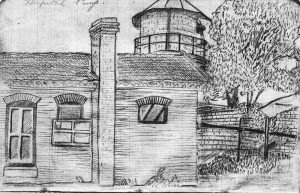

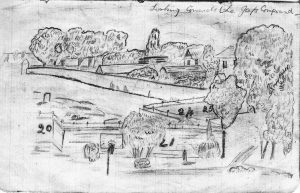

We were to stay in the large concentration camp at Weihsien until the end of the war. At times there were over two thousand prisoners in a compound measuring 200 yards by 150 yards. The food was inadequate, the winters were cold, with only coal dust to keep us warm but the most painful part of those long years was our separation from Mom and Dad. The moment of exquisite Joy on the crowded prison ship remained with me and gave me strength.

We were to stay in the large concentration camp at Weihsien until the end of the war. At times there were over two thousand prisoners in a compound measuring 200 yards by 150 yards. The food was inadequate, the winters were cold, with only coal dust to keep us warm but the most painful part of those long years was our separation from Mom and Dad. The moment of exquisite Joy on the crowded prison ship remained with me and gave me strength.

Surprised by Color

If Lewis used the word Surprise in his description of finding joy, my next experience of exquisite joy was certainly a surprise. Life in the prison camp dragged on during that long hot summer of 1945. Food was getting scarce. We heard rumors that kitchen workers were stealing precious allotments of horse meat to feed their hungry families before it could be shared by the rest of the prisoners.

August 17th was clear, cloudless, and warm. That morning, while we were in class, our attention was caught by the distant drone of an airplane. As it grew louder, we perked up our ears, for very few planes flew over the camp and only at high altitude.

Quite suddenly, the sound grew so loud that we rushed to the windows and looked out. There, unbelievably, was a U.S. bomber flying low over the trees, flying so low that we thought it might touch the topmost branches. It climbed, circled, and came in low again. It was clearly an Allied plane, not Japanese. We could see the bold American star on its flank.

By this time, the whole camp was outside, wildly waving, but also wondering if the Japanese might try to shoot it down. As far as we knew, the war was still on. But the airplane came down towards us so boldly, so exquisitely, that it was an unmistakable reality. The meaning was profound: this plane had come for us, to give us a personal message. Our camp, out in the remote countryside, had been remembered. Could the war really be over?

After passing over us three times, the magical airplane gained altitude and headed away. Next to me, someone gasped. There was a hint of disappointment. Our teacher said “They are leaving us! But perhaps they will come back and set us free.”

Then an even greater marvel took place almost in slow motion. When it was about half a mile away, the plane’s undercarriage opened and seven dots appeared.

It became clear that they were seven airmen, parachuting down, a slowly unfolding miracle. There was no hurry, no rush. Just gravity gently doing its job. And what parachutes! Brilliant colors: red, blue, yellow, green, orange, white and purple.

They contrasted vividly with the shabbiness of the camp. After our years in captivity, most color had faded from our lives, with our drab clothes in tatters, devoid of color, and our food, almost as colorless as it was tasteless. Those brilliant colored parachutes were especially memorable as they graced the reality of seven very real men, dangling from them.

Time stood still for a precious moment as the colors danced before my eyes. What made it extra-special was the totally unexpected nature of this visitation. Like a vision from another world, almost too wonderful to believe—a moment of unspeakable joy that I would recall years later, as precious as my experience on the bow of the prison ship.

Without hesitation and regardless of the possible danger involved, we boys, following several adults, rushed towards the main gate of the camp, burst it open and ran out into the fields with complete abandon.

As I passed through the gate, a couple of guards brought their rifles into firing position. Then, in obvious confusion, the guards slowly lowered them. The sight of the parachutes had made us fearless.

Our goal was to reach the seven airmen. We prisoners were all barefoot, as we normally were during the summer, and the ground was rough with broken glass, scraps of jagged metal and prickly kaoliang stalks, but we did not care.

Half a mile out, in a fie ld high with kaoliang corn, were our seven heroes. They had their automatic rifles at the ready, expecting to have to fight their way into the camp. But they were now taken totally by surprise by this horde of ragtag, barefoot prisoners surrounding them in jubilation.

ld high with kaoliang corn, were our seven heroes. They had their automatic rifles at the ready, expecting to have to fight their way into the camp. But they were now taken totally by surprise by this horde of ragtag, barefoot prisoners surrounding them in jubilation.

I was one of the first to reach Jimmy Moore, an alumnus of Chefoo School, who had volunteered for the mission to help set free his old school chums. His uniform was impeccable. His complexion was ruddy as some Olympian hero, and just to touch his sleeve took away my breath. This was as close to idolizing a human being as a boy could get. Some of the adults and bigger boys carried Jimmy and the other airmen into camp on their shoulders, as we smaller fans tagged along.

Just inside the main gate, Major Steiger, their commanding officer, quickly took charge. He asked to see the Japanese commandant. Steiger was pointed to the hall where the Japanese officers were assembled. He drew his two revolvers and strode in to face the commandant, seated at his desk with his hands spread out in front of him.

We waited outside and were relieved to see Major Steiger coming out with his revolvers holstered and a smile on his face. A peaceful surrender had been accomplished.

It is hard to describe the sensation of freedom that came over me. My friend Theo and I walked out the unguarded gate with a sense of ecstasy. After three and a half years in captivity, it seemed incredible that we now had freedom.

I asked Theo, “Does this mean that we can go wherever we like?” We wandered around outside the main gate, toward the little village of Weihsien, kicking the dust and throwing stones at an old can down in a gully. There were new village smells too: old rotting cabbage in the village dump, chicken manure and wood smoke from a nearby farmhouse.

Since we first came into camp, the world beyond the walls had begun to shrink and seem unreal. Over time, its landscape had become like a two-dimensional stage set. The narrow, colorless existence of confinement was our only reality. Suddenly the outside world became not only three-dimensional but it had taken on a fourth dimension of infinite possibility. That is what our freedom felt like.

This moment of exquisite joy at watching the seven parachutes and its aftermath had the crowning glory of freedom in all its many colors. I was now full of great expectations. These moments were also those of being found, of finding myself, of coming of age. They have helped sustain me over a lifetime.

[Editor’s Note: The pen and ink drawings used here of Camp Weihsien’s entrance, the barracks, and the view over its electrified walls to the surrounding countryside are from a sketchbook the author kept as a boy. This article is adapted from his upcoming memoir. For more information go to johnhoyte.com]