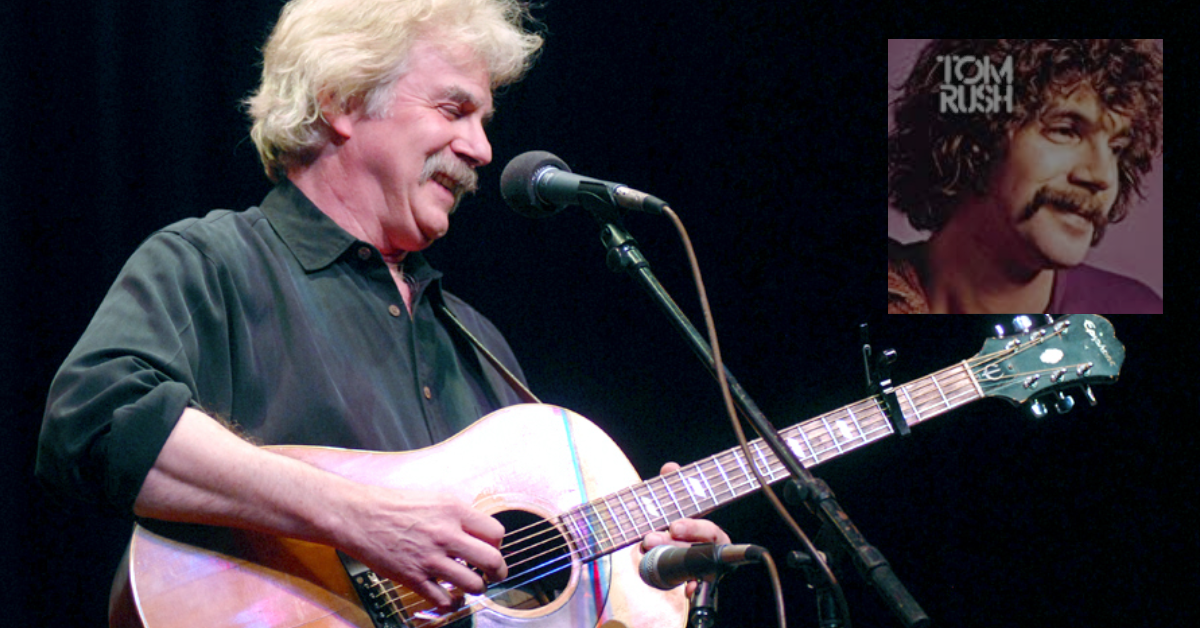

Interviews with Master Musicians #1 – Tom Rush

In 1968 Tom Rush penned and released his timeless folk standard, “No Regrets,” as the last cut on his album, Circle Game. He’s released a total of seventeen albums and entertained millions in a touring career that has spanned sixty years. He came out of the fabled Cambridge folk scene of the 1960s, where those he encountered remain cherished influences.

With his charming, self-deprecating humor, his poet’s heart, and a nature that seems equal parts road worn and perpetually youthful, Rush exemplifies the singer-songwriter—the troubadour—whose musicianship transcends fashion. His life deserves to be seen as a triumph over the vagaries of the music business. Along the way he became a wonderful performer, whose delight in the skill at his command and his wit make him a favorite entertainer, to whose shows people return again and again.

Everyone famous is an “icon” these days: Tom Rush deserves that title because he’s the central figure of a period whose music endures. He’s a legend.

Recently, SCENES was fortunate to have a conversation with Tom Rush in which he discusses his new Patreon series Rockport Sundays; a new book he’s working on called Roadmap; and offers insight into his own creative process and history.

All in all, it is a conversation bursting with Rush’s signature playfulness, his unabashed humanity, and one which reminds us that creativity often flourishes best in community–whether that’s in a smoky Cambridge folk club or, right here, as a part of SCENES.

We hope you enjoy!

****************************************************

(Interviewer) Tom, thank you so much. I really appreciate you doing this.

Oh, you’re very, very welcome; it’s a pleasure.

I’ve had a tremendous amount of fun preparing for this interview. It gave me a chance to go back and listen to so much of the music you made that I love.

You’re prepared. That’s dangerous. [laughs]

Let’s get right to it: you have a new show on Patreon called Rockport Sundays. I’m just wondering if you’d talk a little about that and what your experience has been like with it?

Well, we can talk a lot about it. It’s what I’m pushing right now. Basically, you know, COVID shut the whole industry down. I actually had it back in March and, thankfully, got over it, but I’ve had like 60-70 gigs either cancelled or pushed way down the calendar so far. In other words, I’m suffering from “Audience Deprivation Syndrome” [laughs] —I actually googled ADS to make sure it didn’t stand for some dreadful disease. It actually stands for Automatic Delivery System—which is kind of appropriate in this case.

So I put together this notion that, every Sunday, I would post a new song, maybe a story from the road, or pages from a book I’m writing, and there will be a library with eight of the previous postings which I’m calling “Eight Ways to Sunday.” It’s off to a very good start, and I get to, you know, play in my kitchen or my living room for an imaginary audience that actually then posts all kinds of very supportive comments—so it’s kind of like being on stage but a lot more casual. I get to hang out in my kitchen and not have to get all dressed up, and I get to talk about things like: “Where this song came from,” or “Why am I playing so many different guitars?” —you know, basically just chat, and it’s been a lot of fun.

I listened to a number of the episodes, and am I’m enjoying it. I’m sure your audience will as well, and I hope that audience expands.

Well, yeah, I hope so, too! What I’m doing is sending people to www.tomrush.com, and there is a link that will send you to the Rockport Sundays series where you can sign up.

Let me just, in like two sentences, tell you about our company Scenes. We specialize in supporting emerging artists.

Cool!

We’ve had over 1,500 bands and singer-songwriters perform for us. Some are Voice or American Idol winners and have established audiences, but a lot of them are young performers who have never played for more than fifty people in a bar. We give them a global audience; sometimes their videos reach tens of thousands and, in some cases, even millions, so it’s really cool. It’s the most fun thing I’ve ever done.

Sounds like that’s right up my alley, because I’ve been doing shows under the name Club 47 for years where I put together some well-known artists with some up and coming, unknown people who are brilliant. We basically do a show that fills a symphony hall or Carnegie Hall or wherever—and it gives them a leg up, because they get reviews in the papers, and they play for a couple thousand people who have never heard them before. Then they go home all excited.

Well, that’s so important because—you know, in our digital world—it’s so hard to find the real talent out there.

I’m thinking, in fact, of starting a parallel series to Rockport Sundays called Club 47 where I would get, you know, Jackson Browne to come on with some kid that he’s really excited about to play some songs together—precisely as a way of giving more exposure to some really talented, young people.

That would be great. We’ve been thinking about having a mentorship component of what we do as well, and, in a sense, the interview with you is kind of a start into it. I don’t want to put you in the position of being Moses here, but I do want to ask you some things that I think I might be helpful to young musicians.

Okay, cool!

I’m wondering about your relationship to the audience. It seems to be something that nourishes and sustains you.

It does, and I think a lot of performers would say the same thing. Getting on stage—or, in this case, sitting in the kitchen—and being able to share stuff that you’re excited about with people is kind of what it’s all about, and it’s really rewarding. You know, getting up and saying “Here’s a song I wrote” or a song that maybe I didn’t write but that I’m really in love with and why—and then hopefully the audience agrees that it’s a really good song and sinks into it, which is very rewarding from the performance standpoint.

I imagine you have some fans that have gone to enough of your shows that you’ve gotten to know them a little bit.

That does happen. I mean, I don’t have the Grateful Dead kind that hire a bus and go from show to show, but yea, there are people, especially in the same geographic vicinity, who will show up from year to year and wear the t-shirts they bought last time.

Is one of the secrets to your longevity your pleasure in your skill as a musician? What you can do with a guitar and all the ways you can do it?

I do have fun with that, but I have to confess that I don’t know what I’m doing—guitar teachers get the hives when they see me play. [laughs] I took piano lessons for about 12 years when I was a kid and hated every minute of it, but I really enjoyed playing the guitar and never took any lessons. Actually, I have to back up. After I’d been doing it for about twenty years, I figured, “I should really learn how to do this properly,” and I had one lesson. The guy gave me all these exercises that made my fingers hurt, so I said, “Nah, screw it, I’m making a living doing it the way I do it.”

Basically, I just hunt around the guitar until I find something that sounds good. I don’t know what the chord is called, and I’m probably not doing it properly, but I’ve got this guy working with me now Matt Nakoa on keyboards, who is a really talented musician, and he will tell me what the chord is called, if I need to know.

I just kind of make stuff up, and it works. It sounds good to me, and it apparently sounds good enough to other people that they pay to listen to it. God bless them.

You learned some things from other musicians. On one of the episodes of Rockport Sundays, you talked about how the blues musicians would come to the original Club 47, and you had a chance to talk to them and learn how they did certain things.

Yea, that was such a treat, and that was a really pivotal time in my life. It was a point where I was going to Harvard. My parents wanted me to go there, and they were thinking I was going to become a doctor or a lawyer—you know, do something important. Instead, I went off and became a musician. They were very supportive, but I think, even to her dying day, my mom wanted to know when I was going to get a real job—and I’m still wondering what I’m gonna do when I grow up. [laughs]

But yeah, Club 47 brought in the legends—the folk legends, the blues and bluegrass players, the Irish/Scottish balladeers—and you could hang out and talk to these people, and they turned out to be actual people—not just legends. You could ask them, “How do you do that thing you do?” and, very often, they would show you. Most of them were eager to help.

I want to pursue this a little bit with you in terms of your relationship with other musicians through the years. I’m wondering if there were one or two people you might comment on who had a big impact on you?

Well, I am very easily influenced. Back in those days especially, I was a bit of a sponge. Two artists that would be at the head of the pack would be Josh White, whose recordings really turned me around. I was very much into the Rock n Roll scene of the late fifties, and then I heard a Josh White recording and thought, “Wow! I’ve never heard a guitar played like that; I’ve never heard songs like that. This is wonderful,” and it really got me more focused on folk music.

The other one would be Eric Von Schmidt, who was, in my mind, kind of the keystone of the whole Cambridge/Boston folk scene. He was a little bit older than most of us. He was a graphic artist, but he was also a consummate finder and writer of songs. I just adored his music, his style, everything, and I mimicked him in every way I could. Of course, when I do one of his songs, it now comes out completely different than the way he did because that’s my technique.

When I’m learning somebody else’s songs, I will learn it off the record, but once I’ve figured it out, I won’t listen to the record again. I let it drift from its moorings and become, you know, my version of it, because there’s no point in doing the same thing the original guy did.

I have to ask, with Joan Baez and James Taylor being in that scene, did you guys get to know one another?

Baez was already kind of up and gone by the time I got to town. She was becoming famous and wasn’t playing at the Club 47, except on very rare occasions. I became good buddies with a lot of wonderful players that you’ve probably never heard of though. [laughs]

The Cambridge scene was different from the New York scene; there were a bunch of players who really didn’t care about being professionals. They were very good, but they were typewriter repairmen or psychopharmacologists, so they had some other thing going on in their lives and music was just for the fun of it. It didn’t make them any less good than the professionals—and, in fact, sometimes they were better than the professionals, because they could do whatever they wanted. They didn’t have their careers on the line.

It was a fabulous music scene, and I remember thinking at the time, “This isn’t normal. This can’t be normal,” and, in retrospect, it certainly wasn’t. It was a magical confluence of towering legends in the field and a bunch of really talented kids. It had its amusing inconsistencies, and it was a bit incongruous to have a bunch of Harvard students sitting around singing about how hard it was in the coal mines. We made up in sincerity what we lacked in authenticity; I think.

Isn’t it strange how those magical nodes of talent do geographically come together? Right now, East Nashville and Asheville, NC are nurturing lots of new artists. We get a ton of performers from a handful of thriving music scenes.

Well, I think the lesson that I took away is that great music, almost always, comes out of a community. Nowadays with the internet, that community can be scattered across the globe, but I think the way that you’re influenced, the way that you listen to other people and pick up this or that, is very enlightening. I find a lot of times with the songs I write that I’m listening to somebody else’s music, but whatever occurs to me has nothing to do with what the other person is singing. Listening to somebody else somehow puts your brain into a space where ideas can fly around. Some of them stick, and some of them don’t.

Would you say that, at a certain point, you transitioned from being a recording artist to being more of a touring artist?

I’m not sure that take is accurate, because I was touring all along. The way it worked for me, at least, is that I never made my money off selling records. I’ve always made my living on stage—until this year. I looked at it like the records were a way to promote the shows. In those days, you made a record and the record company would pay for all the expenses, but they would charge it against your royalty account. They would sell the records and were making probably a buck a copy, while the artists were making, maybe, fifteen cents a copy, so it was very difficult to pay off that deficit. You’d basically have to sell a million copies before you saw another dime. The concerts were where most of us, in fact, got to pay the rent.

I was traveling all along. In the early 70s, it just got brutal. There was a five year stretch when I think I had 12 days off—not in a row. Every day was rehearsing, traveling, doing a promo trip, or doing concerts, and I started to realize that, you know, I wasn’t making a ton of money; I was bringing in a ton of money, but it all went out to the managers, the agents, the band— of course, bands have nasty habits of wanting to get paid [laughs]—the hotels, airplanes, road manager, sound tech, etc. It’s a very expensive way of having a business. I started to realize I was the money pump. Basically, I wasn’t an artist in the eyes of the industry: I was the money pump. I caused the money to flow from peoples’ wallets, into their wallets, and I quit at one point. I just got I got so fried that I decided I would quit, and I bought a farm in New Hampshire. I was determined that I was going to be a farmer, and it took me about six months to realize that wasn’t working either. I came away with an abiding respect for people who actually are farmers and can make a go of it.

So, I started little by little going back on the road again but on a much less expensive and ambitious level. It was just me, or me and a small band, and then it grew from there, but the way it works for me now—or did until COVID shut everything down—is that I’m either a solo act, or I have Matt Nakoa with me on keyboards and harmony vocals. Working with him has really been a treat. I urge you and your readers to go to www.mattnakoa.com. He’s a monster talent. My hope is that when he’s playing stadiums, he lets me open the shows.

You were famous during the ‘60s and ‘70s. Did you ever miss it? Or were you glad when the notoriety began to fade?

You know, it’s funny. I’m writing a book called Roadmap, which is actually kind of in-sync with what you’re doing. It’s basically a book about why you probably don’t want to be a touring musician [laughs]. I’m having a lot of fun writing it, and I’m hoping it’s going to be entertaining for people who have more sense than to want to do that.

Well, but that’s the only way emerging artists make money these days, though.

Well, it’s true that if you want to do it, you’ve got to do it onstage. I was just going through my BMI royalties statement, and I decided I would do the math on one little section that had about a dozen entries. It was for Youtube. There were a little over 83,000 plays of my songs in that one section. In other words, 83,000 people listened to my recordings. My royalties for that ended up being 83 cents—one thousandth of a cent per play! It’s going to be really hard to make a living like that. Somebody’s making money, but it’s not the artists. It ain’t good.

You know, on the one hand I’m really pleased that a lot of people are listening to my stuff; on the other hand, somebody else is making a bunch of money on it instead of me—or whoever the artist happens to be—which I don’t think, in general, is very smart thinking on the industry’s part. If the artists quit being artists, then they aren’t going to have much content to show.

Anyway, I’m off on a tangent. We were talking about fame, and I was finishing up a section [in Roadmaps] on fame. I’m doing this from memory, but I think I said, “Fame and I had a few dates, but we never got serious. She still comes over once in a while. She says it’s my fault for not committing enough energy to the relationship, but my take is that she’s just too needy and demanding.”

Fame is a very curious thing, because it’s basically totally subjective. If you’re famous to one person, then you’re famous. If it’s your mom, it probably doesn’t count, but I’ve had people come up to me and say, “Are you famous?” and I say, “I guess not.” [laughs]

That’s right—I’ve had people come up and ask me “Are you someone I should know?” [laughs]

I had one girl come up to me outside a TV studio in England with an album she wanted me to sign, and her comment was, “You’re much taller than your albums!” I always remembered that one.

I wanted to talk to you about another relationship—sometimes these relationships are difficult for musicians—but I want to talk about the one you have with your song, “No Regrets”

Well, I love the song, partly because it put my first two kids through college. It’s the one song of mine that’s really been recorded a lot by other artists—Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Shirley Bassey, and a group in the U.K. called The Walker Brothers had a huge hit with it. Off of that, came a whole bunch of other covers including a rap version that I didn’t recognize, but it was a hit; I won’t complain.

It was actually kind of a made up song. I was living in Cambridge, and this lovely, young lady named Jill Lumpkin, who became my girlfriend long term (meaning probably five or six years), came up from New York to spend the weekend with me. I’d never spent that many days and nights alone with somebody before. I took her to Logan Airport Monday morning; I put her on a plane back to New York, and it felt strange walking away alone, so I went back, and I wrote the song basically imagining it was the end of a long relationship—which, in fact, came true when we split up a few years later. It’s a song that’s been good to have around, because there have been some breakups over the years.

I saw a clip of you talking about this, and you provided an apocryphal ending to the story where she went to Venice and became a streetwalker and drowned.

No, that didn’t actually happen [laughs]

However, even though it didn’t happen, the story seemed to evoke real emotion. It was interesting.

Well, I might have been pretending.

I want to ask you something that I’ve though a lot about, being a child of the sixties; Looking back at the music of that era, with “No Regrets,” “The Circle Game,” “Child’s Song,” and many others, there’s a certain wistfulness to so many of them, which, in retrospect, is kind of odd for music that appeals to young people. It’s almost like a premature nostalgia. There were a lot of songs about loss by people who had their whole lives ahead of them, whereas on your last album, a couple of the songs I like the best: “Far Away” and “Voices” are about actually being able to appreciate and enjoy life.

Well, yeah, I hear what you’re saying. A couple of things come to mind. You mentioned “Child’s Song,” which is about a kid leaving home saying goodbye to his parents. It’s a really true song by Murray McLauchlan in Canada. When he first taught it to me, it took me about six months to toughen up enough to get through it without bursting into tears. I would play it and the kids would all cry, because we were all much younger. Now I play it and the parents cry, because their kids are going off to college. It’s a very true song about something that happens to us in life—you know, growing up and separating from our families, forming new families.

The other thing is that some of the other songs you’re citing—“Far Away,” for instance, which sounds like it’s about an ongoing relationship and a guy saying: Tell my troubles I’m not home today, Lie here in my arms we’ll sing another song, Tell the world we’ve gone so far away— in fact, I wrote after my wife and I had split up, so it was kind of a wishful thinking song.

One of the beautiful things about your career is that you’re still making great music. I was wondering about how your sources of inspiration have changed over the years, or if they have? One of the things I think about is how certain musicians and poets create their best work when they’re young—like Keats who died at 26—while, on the other hand, Yeats’ last poems were among his greatest.

Well, I’m not entirely sure how to answer that. I’ve been told the Voices album, my most recent, contains a third of the songs I’ve ever written in my career. I’m writing a lot more. I’ve even got enough songs for another album right now, and I don’t know quite why that’s happening. I can tell you that I don’t write songs on purpose. I can’t sit down and say, “Okay, I’m gonna write a song today about this topic.” That doesn’t work for me.

It works well for Tom Paxton and a lot of my friends who I respect a lot, but I just sit down with a guitar. It usually works the best early in the morning before I’m really awake. I noodle around, and these ideas start drifting through the room. Sometimes I manage to catch them before they drift out again. I scribble them down. Some of them stick together, and I think, “Oh, that could be a verse” or “That’s a good idea for a song,” and I’ll have a little scrap of music attached.

Basically, it’ll grow from that, but I don’t know where the songs come from. My theory is that there is an orbiting cloud (like a comet) of songs out there somewhere beyond Jupiter, and they come zooming in from time to time. [laughs] If you’re lucky, you get to catch them. I sometimes keep my phone by the bed, and I’ll have brilliant ideas in the middle of the night. I’ll grab the phone and sing into the phone. Then in the morning I have to figure out what I meant by [slurring scat sounds]

“(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” was first recorded on a like that, and Keith Richards couldn’t remember having made the recording when he woke up. It was just there on his little machine.

Yeah, I love that image of waking up in the morning with the tape machine going *flap-flap-flap-flap*.

Last question, what has the experience of writing Roadmap been like?

Well, it’s, again, been a lot of fun. The premise of the book is that you can make a million mistakes in this business, and I have made most of them at least twice, so I’m trying to basically steer the young, aspiring musician away—give them a little bit of experience, as it were, ahead of time, so that they don’t have to make the same dumb mistakes that I did.

I’ve got about two hundred pages—mind you they’re scattered all over the place—and I’ve written the same things two or three times in some cases. One of the good things about the Rockport Sundays format is that it’s going to force me to finish songs that are halfway done, as well as finish this book, get it organized, spruced up, and actually presentable, which is something I just haven’t had time to do. Now I’ve got an incentive to do it, because I want to present it to the subscribers.

I started out thinking, “I don’t know anything about showbiz,” and then I started to imagine I was following somebody around showing them, you know, how to position a microphone, how to conduct a soundcheck, how not to piss off the sound man—because you DO NOT want the sound man mad at you. The sound man and the dentist are the two people you do not want mad at you. [laughs]

I am already posting excerpts from Roadmap. One of those excerpts is up in the collection of previous episodes, and, when I’m reading installments on Rockport Sundays, I read the pages, but I also send out a PDF of them at the same time, so people can print them out and basically assemble what will be a first draft—if they want. I’m encouraging people to share that. You can’t download the music and share it, but you can share Roadmap.

I’m also working on a novel and an autobiography at the same time, but we’ll talk about those in another decade or so.

***************************************************************

Great thanks to the one and only Tom Rush for talking with SCENES. Thanks, as well, to our contributors and readers who make our content possible and rewarding. We are a community!

_______________________________________________________

Additional editing of this interview was supplied by John Dennis.