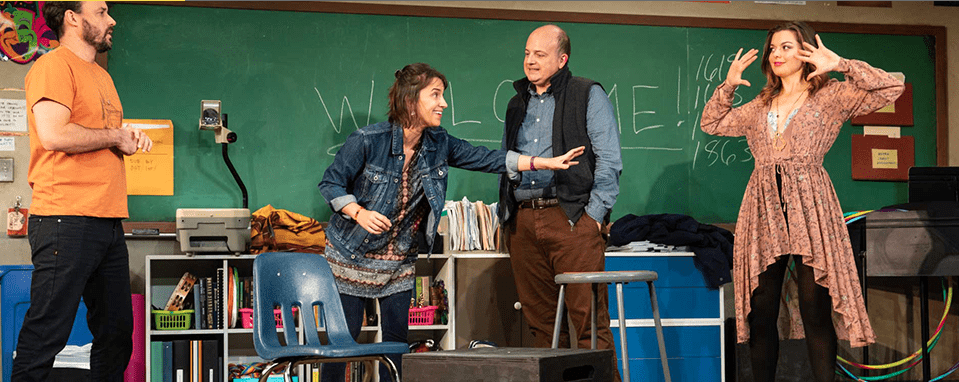

All told you could do a lot worse than ninety minutes of breezy theatrical fun. Larissa Fasthorse’s takes place inside a public elementary school classroom. Director Logan (Jennifer Bareilles) has won numerous grants to put on a play about Thanksgiving. The catch: it has to conform to all sorts of politically-correct terminology and content. Bareilles also has a school board and parents to contend with and an existing petition to have her ousted from school drama performances altogether. She has cast her very vegan and equally eco- conscious boyfriend Jaxton (Greg Keller) as the male lead—they don’t kiss or touch, they “couple” and “decouple.” And he’s not really an actor, he’s a street performer—albeit one of relative note who has won a corner all to himself once a week at a local farmer’s market. Caden (Jeffrey Bean) is a thin middle-aged nerd who has done reams of research for this play—his dream is to hear his words spoken out loud on stage—something that has eluded him in his 66 first completed plays…He’s quite funny as an adult nerd and one of his jokes about dramaturges elicited loud chuckles from the audience from the audience at Playwright’s Horizon.

The fourth actor Alicia, the female lead in the play they are putting together is played with obvious abandon by the curvaceous Margo Seibert—she’s a prototypical dumb blonde, except she’s a brunette. Logan has cast her because the rest of the cast is white and she believes Alicia to be Native American, but was fooled it turns out by one of the actress’s four “ethnic headshots”—the one in which she wears Native American headdress. Alicia is as white as it gets, it turns out. You begin to get the drift of this play.

In keeping with the PC absurdity at hand, Logan wants the play to be wholly “devised” i.e. improvised. One of the things that works best here is the constant undermining of vocabulary and intent—the more Logan and Jaxton attempt to be politically correct devising this “Native American Genocide Day” play, the more they get lost in a maze of non–meaning. The skits that they re-enact are selections from real lesson plan suggestions shared by teachers for classroom Thanksgiving activities: one of them actually has teachers dividing students into Pilgrims and Indians “so the Indians can practice sharing.”

Fasthorse herself is half Lakota and half Norwegian, an accomplished educator and playwright who founded The Children’s Theater Company. While Fasthorse is an established talent, her farcical take on political correctness reflects something new (and possibly emerging) on the New York City play scene. The more you know about the director’s life, however—her disappointment with Hollywood and commercial television, the more The Thanksgving Play makes sense. Presented like a children’s play itself, along with costumes and traditional turkey day songs and traditions that are duly made fun of, the play makes the viewer think about how everyday content that is presented to children can actually be loaded with intended and unintended signifiers. The trick, Fasthorse shows us here, is how to unpack these received notions and present a viable, alternative that is fair to all, including well-meaning white people who also wish to set the record straight. At times the play gets childish itself and the four characters are to a certain extent one-trick ponies: there’s no opposing view or character to create true tension or dramatic verve. The Thanksgiving Play isn’t Beckett or Mamet or Shakespeare—but Fasthorse never intended it to be. If you are up for a light night out, a few laughs and a few hard facts of American history to ponder afterwards, then this might be the play for you.