Over the weekend, I heard something that I never imagined possible. It is music written exclusively for the human voice – music from the High Middle Ages that gave birth to modernity as we know it – re-imagined and re-presented for electronic instruments only. The results are mind blowing, and it’s not just about one song or one genre It’s about what the results tell us about the human imagination and its interaction with the flow of time.

The musical shift in the early Renaissance came about from changes in economics and technology. It was possible then, thanks to the innovation of the music staff, to write down music in multiple parts. The echos in cathedrals enticed musicians with mental sounds of notes stacked vertically as high as the churches, even reaching into the heavens. In addition, the emergent prosperity in Europe and the end of the Black Death was cause for celebration – more beauty in music to signal the possibility of material progress.

Ultimately, however, this was about more than that. It’s pretty much impossible to listen to 16th-century polyphonic music without understanding the scholastic view of truth that motivated its composition.

Heaven and Earth

The scholastics, typically dated from St. Thomas Aquinas in the late Middle Ages, believed in the unity of all truth. Not that all truth was knowable, but it is potentially integratable. Whatever was true in one discipline had also to be true in every other discipline; one truth, stretching infinitely vertical but also horizontally to infinite applications. Similarly, whatever was true in the course of time in this world is a reflection of a truth that God ordained to be so outside of time.

The model went as follows. There is the forward march of time, which is the world you and I know, experience, report on, and it is defined by struggle, triumph over nature, and a sad ending that comes with mortality, dust to dust. On the other side of life, there is new life in a complete world that lives outside of time, birth, and death. It is the transcendent realm, a kind of place where we can live at one with God and in full knowledge of all that is true. This was Heaven.

This model implies a certain well-known geography, which is metaphorical but aids in understanding. Time is what you experience in life. Heaven is ascendant and transcendent. It is a realm somewhere up there that is out of time. And of course there is also Purgatory (which exists within time but is only known after death) as well as Hell, the eternal foil to paradise.

The highest goal of life on earth – and this goes for art, liturgy, learning, technology, science, commerce – was to reach outside of time and touch (or see or feel) that heavenly realm. Doing so, it was believed, would inspire us toward better lives because it would fire the imagination toward the goal of all our mental and spiritual actions, to love God and others ever more perfectly. Also, it’s psychologically and spiritually awesome to gain a glimpse of God or even to touch the Presence.

Eternity to Taste and Hear

This sensibility is embodied in Eucharistic theology, in which the faithful are granted the privilege of literally consuming the body of Christ. It is a way for time to touch eternity in the most tangible possible way, literally draw on the transcendent as a source of life and salvation. The art created in light of this sensibility was structured to achieve this very Eucharistic effect, to create visuals and sound that permit us some slight hint of access to the eternal.

What does eternity sound like? This was the task of the 16th-century masters to discover. And this task – which is not so much didactic as experiential – inspired vast creativity all over England and the Continent. There was Victoria in Spain, Tallis in England, Josquin in France, Palestrina in Italy, Di Lasso in the Netherlands, Isaac in Germany, and literally thousands of other musicians who contributed to the task. And their legacies are remarkable. Their music can still today transport your mind to another realm, exactly as the Scholastic model suggests.

The Human Voice

But if the goal of this music is to cause the human mind to leave time for a world beyond mortality, there was still the issue of the technology of delivery. The human voice was seen as an ideal method of performing music because the human person is made in the image of God. The breath that creates song was seen as an exhalation of the breath that God infused in us initially to give us life.

That is true, but humans are fallible and imperfect, and even the greatest singers can never perfectly perform even the holiest music. It will always be compromised by the limits of the body. This is one reason the organ became a valued instrument in the Middle Ages: its bellows mimicked the functioning of the human body but improved on the stability of sound.

Let us just imagine that we could take that same music and remove the human performance element from it completely. This would require technology that was not available in the golden age of polyphony.

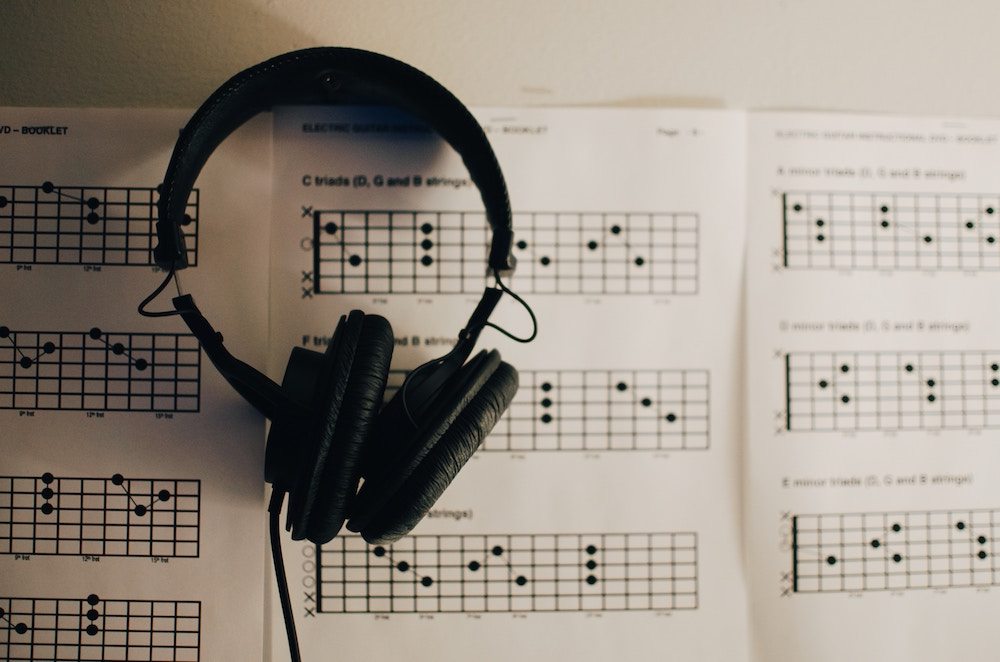

A musician and technologist did just this. His name is Richard Galbraith. He put together an entire album of exactly this, polyphony performed on synthesizer. Here is his YouTube channel.

Now, to be sure, I have a special interest in this music, having conducted it for a decade with a choir that specializes in performing it in a liturgical context. So, yes, I’m invested. But even for a person that does not know this music, the sound is remarkable, ethereal, transporting. I think I can go further and say perhaps that this is the most perfect rendering, and one over which the composers themselves would have rejoiced.

How I would love to be with Palestrina or Tallis or any of them and be present for their first hearing.

I’m delighted to present this to you now. Here is “Salve intemerata,” a Marian hymn put to music by the great Thomas Tallis. Here is the vocal version and here’s the sheet music. Now enjoy a new presentation made possible by new technology. Keep in mind that this is not some kind of corruption. It cannot be. The music would not have existed without technology: the cathedral, the musical staff, the vellum paper, ink, and so on.

Thus is born a new way of understanding and touching the eternal.

This column originally appeared at The Foundation for Economic Education, and is reprinted by permission.