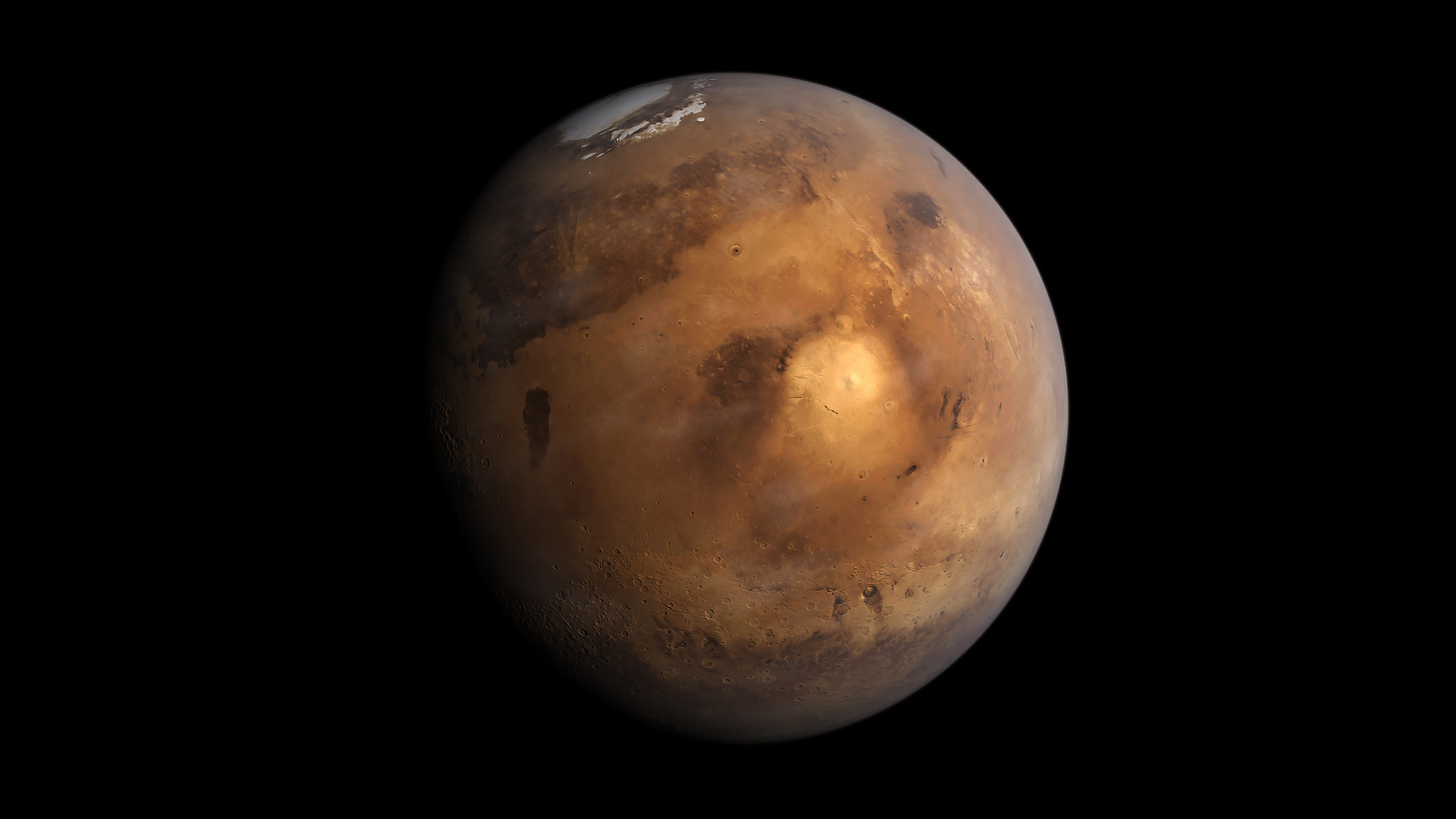

The sun rises strangely on Mars. It is smaller, a white coin tinted red by the swirling dust. Up it goes, a pale dot turning the gray haze of alien shadows into a sea of fire. I watch it every morning I can, staring across the vast wastes at the distant mountains. One part of my soul takes it as a reminder of home, a touchstone of normalcy in a wilderness beyond the heavens. Another part recognizes how subtly exotic it is, and embraces the thrill of adventure. I came to this planet by choice, as I come to these cliffs. But my home is still in another place.

As the months wind on, it is hard not to notice the changes. The sandy lowlands that lie before me are no longer the desert they once were. Our work has largely been successful, and the temperature and atmospheric pressure have risen enough to permit the briny slush that slides down from the heights in the summer to collect and remain in liquid form year-round. The vast swamps are fast becoming a lake, and soon the lake will become a sea. If all goes well, the dunes I once walked on will become the bed of a Martian ocean.

The wind picked up. A cloud drifted across the sun. That was new—a real cloud. In the weeks leading up to that morning, additional efforts had been made to melt the polar ice caps, and the atmospheric team had been taking further steps to make the chemical composition of the Martian skies more earthlike. It was a welcome change, though at first those of us on the ground crew had feared the possibility of storms. Terraforming is a young science, full of mystery, and not a little risk.

It was probably that cloud that helped me notice the approaching craft. While its shadow covered the area I was standing in, the sun still struck that distant windshield, a bright glint in the momentary shade. The vehicle moved quickly, skimming across the surface of the briny wetland. The use of hovercrafts had become inexpensive in terms of fuel, but I still found it odd that someone from another crew would be venturing towards our territory this early in the morning. It was a rare enough occurrence at any time of day, and I had heard of no transmission telling us to be on the lookout.

It was a long time before the craft drew near, hovering over the dark mud. Through the window I saw a single pilot. He nudged the machine over onto the rocky shore, and ascended a few dozen yards to a flat place where he could land easily. When the door opened, I could see that he was alone; no passengers had come with him. His helmeted face bore vaguely east Asian features, and as he walked, I could see he was bent with long years of hard labor.

“Ganyan nuzhen! Nageshmatz duzhlak pinya!”

He sounded desperate, but I could not understand the words. The sound of them was familiar, though. I held up my hand, asking for him to wait, and contacted the lab.

“Walter, it’s Sharon. Are you still awake?”

“Awake and monitoring, Shar. What’s up?”

“I have a man down here, looks like a miner. He’s speaking EOT.”

“Hold on, I’ll get Darrel.”

East Orbital Trade is a pidgin some of the Pacific-based spacefaring companies use. Most of our group came from the Gulf or the North Atlantic, but Darrel had spent time in Seattle and Vancouver. While Walter went to find him, I motioned for the stranger to sit on some nearby rocks. He looked puzzled for a minute, then nodded and sat down, apparently trying to collect himself.

“Sharon, this is Darrel. Is he on the open channel?”

“Yeah, he can hear you.”

There was a pop, and now Darrel’s voice only came from one side of the helmet.

“Alright, I have it split. What you hear from this speaker is just me and you. What you hear from the other is open channel. The mics work the same way. Change the audio balance if you want to speak just to me. Alright?”

I activated a panel on my left glove and went to the audio settings, sliding the balance entirely to the left.

“I copy.”

“Good.”

I moved the balance back to neutral and listened as a babble of oddly Slavic sounding words passed back and forth between the miner and Darrel. From the tone, it was easy to see that the stranger was tense, but he was nodding and listening and doing his best to remain calm.

“Alright, Sharon,” it was the private channel, “There was an accident late last night at B plant over at the Daryong colony. Something fell out of the sky, left a crater where the habitat used to be. Mr. Mutenkken here is the only one who made it out. Sharon, B plant was the northernmost plant they had. He was too far away to reach his own people, so he came here for help.”

I heard Walter swear at the other end. “I told them not to do this!”

“Walt, it’s fine. We have a spare bunk.”

There was moment’s pause before I heard Darrel’s voice again.

“But we don’t have the resources. Sharon, the supply shuttle didn’t land last night.”

“What are you saying?”

“I’m saying, how often does a large piece of space debris crash into a Martian colony? That was our shuttle. We have to cut back on rations starting now. There’s no room for him.

“We have emergency rations; we can afford to cut back. It won’t be a problem if we share the food deficit equally.”

“Yes it will, Sharon. The emergency rations are due to expire this month. That resupply was supposed to replace them before they went bad. We’re walking a razor’s edge, and this guy, guaranteed, will tip us over. If we make room for him, some of us won’t make it to the next shipment.”

“What are you suggesting?”

It was Walter that answered. “We have to cut him loose. We can’t help him.”

“I won’t do that.”

“It’s not your choice.”

“It’s not yours, either. I’m coming back with him, and when I get there, I’m talking to the whole lab. You can make your argument to them, I’m not buying. And you can make them to his face, Walter. He’s a human being.”

“Sharon, list—,” I cut them off. He was still on the rock, waiting. He appeared calmer than he had when he first arrived. He must have had no idea what he had walked into.

“Mr. Mutenkken!” I said, waving. He couldn’t hear me with the comms off, but it didn’t matter. I couldn’t speak the language, anyway. Instead I motioned back to my rover and the path upslope. He nodded and followed me over to it. The thing was cramped, barely the size of a golf cart, though the wheels were much bigger. He had wide shoulders for his size, keeping me pressed against my side of the vehicle despite what were clearly his best efforts not to. He was mouthing something unintelligible, but his apologetic face communicated all it needed to. I just smiled.

The whole way back I was turning the problem over in my head. I hated what Walter and Darrel had suggested. We couldn’t let this man die, and I knew most of the others wouldn’t want to. Still, self-preservation was a powerful impulse. And besides, Walter was right. If things were really that bad, we had hard times ahead of us anyways. A single extra wouldn’t just be a threat to any one of us, it was a threat to all of us. Self-preservation, sure, but that this more than self-interest. For the sakes of our friends—lovers, in some cases—and for the sake of the expedition, they would vote to cut him loose.

What if I offered to feed him from my own provisions? Then only I would be in danger. Maybe it would give us enough time to contact Daryong and have them send a transport around the long way with some extra food, or even to bring the stranger back. But no, that would never work. The distance was too great for a small, solar-powered transport. They would have to use a large one, and it would be a major waste of fuel, which they couldn’t afford, and of their own rations. Leaving that out, it was still a dangerous trek. No, any chance of reconnecting with Daryong had died in whatever disaster had driven the miner our direction.

As that narrow road winds through the rocky crags of the high red slopes, there is a bend which looks over a narrow valley, the kind that is green with trees back home. I am a botanist with the colony, specializing in plants that can survive in extreme environments. It was my hope to see flowers in that valley at some point. Of course, that was ages in the future. Bacteria was beginning to thrive, but algae and fungal life were still struggling when left on their own at surface level. Of course, below the surface the story was different.

I pulled the vehicle to a halt, and Mr. Mutenkken looked around the barren waste in confusion. I was fumbling so badly in my excitement, it was several moments before I managed to get the comms back on.

“Walt! Walt, are you there?”

“Still here, Sharon. What’s wrong?”

“The Garden! Walt, we can use the Garden!”

At first he didn’t answer.

“Okay, Sharon, we’ll give it a look. Sam Price is down there testing the algae right now. Why don’t you head straight over?”

“Already moving.”

The Garden was one of our more expensive side projects, kept alive only through the funding of an anonymous investor back home. Concealed in one of the deepest cave systems yet discovered on that planet, and modified with the aid of several mining engineers, was a complex of rooms lit with artificial sunlight and separated out into miniature greenhouses. Unlike buildings on the surface, these were not supported by air purification systems or their own supply of oxygen. The hope was that, starting from the deepest chamber and working our way out, the things we grew there would transform the atmosphere on their own. It was a microcosm of Mars itself, a hopeful attempt to do in one small corner what we were already attempting on a planetary scale.

The track that winds that way is tortuous, a narrow defile in the crags of the cliff our little colony was perched on. As I piloted the vehicle through those twists and turns, across draws the seasonal flows had begun to carve into the rocks, Mr. Mutenkken was growing more nervous. I reached over and squeezed his hand, hoping to reassure him. He met my eyes for a second, and smiled.

The entrance to the caverns lies up a gentle slope at the end of the ravine. There is a level area there, and Sam Price’s rover was already parked on it. I set ours beside it, and motioned for the stranger to follow me. He must have been puzzled at that narrow break in the rock, covered with only the thin plastic that makes up greenhouse walls back home. I signaled that he should keep his helmet on, and we went inside.

That first room is barren, the only difference between it and the outside world a mere addition of a few degrees of temperature. But on the far side a set of tracks is angled downwards, beside a footpath, both twisting sharply down to disappear into the darkness. I searched the comms channels until I found the one Sam was on.

“Sam, it’s Sharon. Did Walt tell you about our visitor?”

“Hi, Sharon. Yeah, I heard. The Tunnel Rat’s headed back your way.”

“Thanks.”

The Tunnel Rat is our transport system for the Garden. While we keep the footpath as a precautionary measure, the cave system is far too extensive to be walked easily in a single day. The Tunnel Rat runs on a set of tracks that crisscross through every hall and chamber. It has no separate air regulation of its own, and passes through sliding doors as it enters each new room. The integrity of the experiment is our top priority.

It finally arrived, and Mr. Mutenkken and I sat on the foremost pair of the six bucket seats. There was also a large bed in the back for equipment, but it was empty that day. As soon as we were buckled in, and I had advised him to keep his arms inside, we set off at the fastest speed the little train was capable of. It wasn’t much.

Our passage into the first several chambers was not much different from our first entrance into the system. The temperature climbed a bit each time, but in the immense chill of the average Martian day, that was hardly noteworthy. But as each room passed by, each artificial sun brightly shining, my companion began to look about more curiously. Eventually the rocks started changing colors, accruing a thin dusting of extremophile bacteria. Deeper and deeper we went, and the color changes became more noticeable, the corners crammed with organic-looking sludge. This was a revelation to the miner, but I knew what lay ahead.

At a certain point, there is a fork in the path. We took the right side, one that rose for several meters before angling sharply downward again. Here gravity would have taken the Tunnel Rat down at alarming speeds if it were not for its automated braking system. Down we sped, deeper into the Martian rock. Wall after wall of green, translucent plastic passed us by, lamp after shining lamp. The temperature increased more and more, and I knew the atmosphere was growing thicker, its composition changing. We were testing it regularly, and had been surprised more than once by the results.

At last, after dozens of slime-coated rooms had passed us by, after frost began appearing, and slowly turned to dew, we reached the bottom-most portions of the cave. Here we kept immense tanks of algae, industriously absorbing the abundant carbon dioxide of the Martian air, and churning out oxygen. My companion tapped me on the shoulder and pointed excitedly, chattering away in EOT. I just nodded at his childlike glee, and watched it increase as we passed into the next few chambers.

These housed tanks of algae as well, but with the addition of a lichen crawling across the rocks. That symbiotic combination of algae and fungus was common enough on Earth, but here it looked startlingly alien. We passed it by, and soon entered chambers where fungi were growing on their own. Not quite the grand mushrooms of my garden back home, but large enough under the circumstances.

The last chamber was the true heart of the Garden. It was a cavern far larger than everything that had come before, and was subdivided into several independent greenhouses, most over against the walls or on the rocky rises that were scattered about the center. There were algae tanks in most of them, growing lichens and fungi, and other botanical experiments. More startling to the newcomer, however, were the ponds that sat between the greenhouses. Algae grew here, as in the tanks, but with far less help from us. Sam squatted on the edge of one of them, testing the water.

“Hi, Sharon,” he said, standing up, “Is this our visitor?”

“Mr. Mutenkken.”

They shook hands, then Sam waved towards the back of the cavern, “Want to check out the big one?”

“Let’s do it,” I answered.

The biggest greenhouse was on a high ledge in the back, perched above a few small ponds. It held our most forward-thinking experiments. I headed that way, not even waiting as Sam and stumbled through some halting EOT with the miner. We were ahead of schedule, and what we were about to do would set back our experiment a ways. On the other hand, this was exactly what we had intended it for.

I entered the little door quickly, and the others followed, shutting it behind them. It was as if we had been transported into a jungle. Here there were real plants, purple shiso and milk thistle, a variety of riverbank grape, and small stand of pawpaws, not exactly thriving, but doing far better than we could have guessed. It was these I approached, taking one of the fruits in my hand. They were all edible, but this one really looked like it.

“We can do it, Sam. We have enough here to feed him until the next resupply. We can process the algae, too. We can do it.”

He stood next to me and ran his hands through the leaves.

“We can. We might lose the investment, though.”

I shook my head.

“We won’t.”

For a moment we just stood there. I felt Mr. Mutenkken’s hand on my shoulder, and turned to meet his eyes. They were filled with hope. I smiled again, and nodded, sweeping my hand out to the vast garden. Here it was—his salvation, and the first glimpse of new life in this barren world.

Caught in the wonder of the moment, I looked up, and thought of all the vast tons of rock above us, of the sandy hills, the frosted mountains, and thin atmosphere. I thought of the swamps slowly expanding in the valley, of the orbiting stations doing what they could to change the skies. Every sunrise came back to me, every sunrise here and at home. And in that moment, I reached up, and unfastened my helmet. The others jumped back, startled and not quite registering what was happening. I was not sure I knew. But it came off smoothly, and the breathing system on my suit shut off automatically.

For the first time in the planet’s history, human breath puffed out into cool, unfiltered Martian air. I could see my breath in a cloud before me. I filled my lungs again.

And lived.