I Cannot Imagine My Life without Music

We sat in the engineer’s booth watching through the sound-dampening glass. Over the previous few days of long studio hours we had laid down most of the basic tracks: vocals layered over rhythm guitar or piano chords, with maybe some bass and percussion. Now it was time for our guest studio musicians to add their talents to the project.

The Accordion Player Moment

Our accordion player sat on the other side of the glass, one of his gorgeous handmade Italian accordions in his arms. We could see his expression as he listened to our song through the headphones, entering into the mood and hearing in his head what he might play to serve that song. His hands moved with the melody as though he were conducting an orchestra only he saw. When, after several minutes of listening, he began to pump his instrument and caress the keys—and I heard on my side of the glass the sound of his beautiful playing accompanying the song I had co-written—my eyes filled up with tears. I was overwhelmed.

I knew the pedigree of this musician—the reputation he had as one of the best, not only in Nashville, but in the country, and the long list of famous recording artists he had worked with. A few days earlier I had gone to a well-known music venue and watched him perform in a band whose members were household names and must have had at least fifty major music awards among them. What I didn’t know was what a gracious, humble, and generous human being he was. Indeed, knowing he had worked with many musicians and songwriters dramatically more talented (and famous) than I, I feared he would be disdainful of our music.

Yet he poured his heart into those songs. He didn’t come to the studio to build up his own reputation and fame; in humility he was there to serve the music itself. He talked with us about our vision and what we hoped for, and then he just listened to the music. When he finally began to play, I knew he understood the song. He captured it. He didn’t merely add bits of ornamentation to the edges; he entered the very core of that music and carried it and transformed it into something more full and beautiful than I could have imagined… and yet it still remained my song.

[Editor’s Note: Have a listen to Dickerson and Nop’s “Presence,” featuring Phil Keaggy on guitar and Jeff Taylor on accordion.]

My Life in Music & Otherwise

I cannot imagine life without music.

I am not a professional musician. I make a few dollars here and there performing concerts, and I’ve written a handful of songs that have garnered radio airplay in blues, Americana, and gospel genres. But I don’t put food on my table or pay the rent by writing or performing music, singing, or playing an instrument.

Yet, I cannot imagine life without listening to music, playing music, and writing music.

I am a novelist and an essayist. I teach at a college and write as a profession. I’ve published a dozen or so books, and several dozen magazine and newspaper articles and book chapters. And I do a lot of speaking. To the extent that I am known for anything, these are what I am best known for.

Nonetheless I consider music a vital extension of my creative life. I love the written and spoken word, and yet there is something present in music and songs—whether I am listening, writing, or performing them—that a text by itself is missing. What that something is, I am still trying to put my finger on. Writing this reflection is an effort in that direction.

The Mystery of a Song

I have many poet friends with whom I have had conversations about the difference between song lyrics and poetry. Of course there are similarities: common elements of craft necessary to both forms. Creative art of all forms is rooted in concrete details. It depends on particulars, not generalities. Both the song lyricist and the poet need to work with potent images, or narratives, and not with abstractions or principles. Images reach into our imaginations and grab us; they are able to speak to different people at different times in different ways. Both poems and songs work that way.

But there are also differences between the two. A great song does not necessarily make a great poem, and vice versa. Many of the favorite songs I have written, although I might describe the lyrics as “poetic,” would not work well as poems. Indeed, of the hundreds of songs I have written in my life, I consider only a few to be good poetry apart from the music.

Ironically, the song lyric I think is my best poem is one that began as an instrumental piece without words at all. After I finished writing the instrumental guitar piece, I found it evoked for me a particular mood and image of both the beauty and fragility of life—of something soft and delicate and maybe a little sad yet also joyful. I titled the song accordingly: “Mayfly.”

Almost as soon as I gave the song a title, the lyrics began to arise unbidden in my thoughts. “Rise up and fly on white wings / hear the silent call of the evening sky.” Essentially I wrote an ekphrastic poem—a verbal description of another piece of art, in this case music. That has happened only once. It happened because the mood of the music evoked the imagery so powerfully. And though I almost settled with the song as an instrumental piece, I like it so much better now that it has lyrics.

But back to the difference between writing and song writing—between poems and lyrics.

It goes beyond just the distinction between meter and rhythm (though that is part of it.). In one way, the task of a poet is more difficult than that of a songwriter. I say that as one who holds illusions of being a passably good songwriter, but no illusion of being a poet.

When I write song lyrics, I can trust that some of the emotion or mood will be conveyed by the music—the chord structure, rhythm, and dynamics, the way the melody works, and even the way it is arranged instrumentally. A poet cannot rely on that, and must convey everything through words alone. A poet must accomplish more with a single resource.

Yet in another way, writing a song is a more difficult task. When the poet has written her words, the poem is done. When the songwriter finishes the lyrics, her task has barely begun. She must then struggle to find music that captures those words: melody and harmony and rhythm and instrumentation. Though it is possible to separate them and think of them in isolation—you can look at the lyrics without the music, or listen to the music independent of the words—for the song to work well the lyrics and the music must form a cohesive whole. I have pages and pages of lyrics I have written (and really like) that are languishing; they have never become songs because I have not been able to create music that captures the feeling I sought to evoke with the word-images, or the mood I want to capture in the narrative.

In contrast, for many of the best songwriters I know the lyrics and music come together; they grow simultaneously from the hard work and creative imagination of the songwriter. Or, as happened for me with “Mayfly,” the music comes first and evokes the words.

And then, finally, when I have finished writing a song—when I have a melody and chords to go with my lyrics—still the task is not complete. I then bring that song to my quartet and we work in collaboration to make something out of it, each member pouring into the song his or her own creative ideas.

Or I bring it to the studio, and my producer listens to the song, and we talk about my vision for it, and he imagines how he might arrange it and what other instrumentation might realize the song’s potential. Our two approaches work in collaboration.

[Dickerson and Nop’s “River of Mercy” features Garth Justice on percussion, Peter Wahlers on bass, as well as Keaggy on guitar and Taylor on accordion]

Recording Our Latest with Guitar Virtuosos

The experience I had with the accordion player happened again—in fact, several times—during the recording of our recent album. The drummer on the project did more than just play the beat and reflect the dynamics; he went through his room-sized collection of snares looking for one whose texture would fit the song perfectly. And then he did the same thing with mallets.

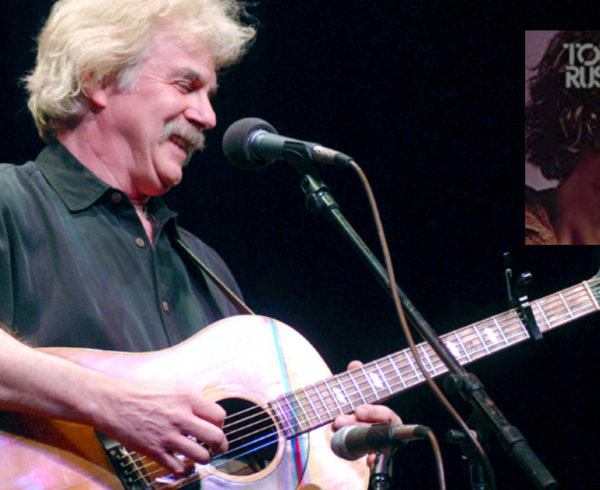

Two of my favorite guitarists also contributed to the project, one whose work I have admired since the early 1970s and have seen in concert at least ten times during that period, and another who played in two of my favorite bands of the 1990s and 2000s. They brought to the project more musical talent in their little fingers than I have in my body.

Indeed, they brought more than just talent. They brought passion and a certain type of humility. At one point, one of them was listening to a song, and his own eyes welled for a moment as he made a personal connection between his story and ours. And then when he recorded his part on that song, he brought to it far more than mere technical proficiency or genius (which were certainly considerable in and of themselves); he invested himself. His guitar part carries exactly what we were trying to communicate, even without the words.

I rarely like to listen to my own songs after I record them. But I now listen to several songs on that album repeatedly, not because I am listening to my own songwriting—though I suppose I am—but because I am listening to something more.

The Passion of a Song

Which brings me back to where I started and why music does something for me that no other form of art does. A song has so many components—lyrics, melody, chords, rhythm, instrumentation and arrangement—but though we can study each in isolation, the song is much more than simply the sum of its parts. A good song works powerfully as a whole. It has all that a great poem has. And all that a piece of music has. Combined.

Attempts to express this in words—a good song transports me?—sound cliché. But they are true. The one word that comes to mind that conveys this most clearly is passion. I think a great song—meaning not just a great bit of songwriting, but a great recording and performance of that song, is powerful—because it is full of passion; one conveyed by the entire person. The fullness of song is better able to carry the fullness of that person than any one component alone.

The late Mark Heard (1951-1992) is perhaps the best example of this I know. He is the songwriter I most aspire to be like—the one whose music has most consistently moved me, informed me, challenged me, enlightened me. There is a quality to his songs, and the way he recorded and performed them that was hard to categorize.

His music was never a great commercial success. (“He says ‘Damn the cool-headed and the setters of goals / Who feel no evil, no heat, no cold / Who wouldn’t know passion if it swallowed them whole’” – Mark Heard, “Big Wheels Roll”) But twenty-five years after his death I keep meeting people whose lives were impacted by his music. And those with the best vocabulary for describing it often come back to that word “passion.” The fullness of a song—that combination of lyrics, music, and performance—seems best able to convey it.

If my songwriting ever comes within a stone’s throw of Mark Heard’s, I’ll be content. But whether I ever reach that goal, I will continue to write and play songs, and make music a part of my life, as long as I am able.